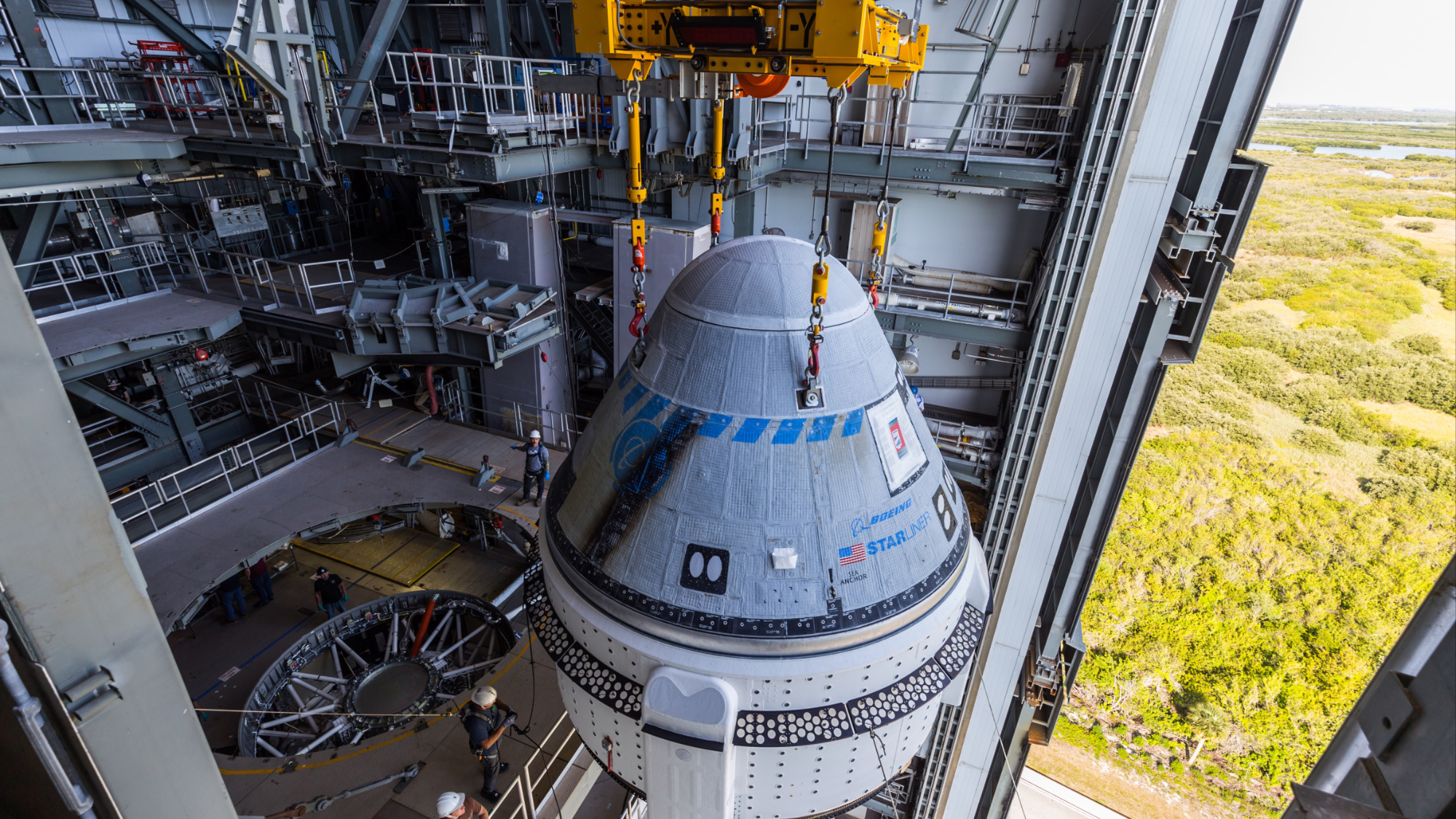

Boeing Starliner astronauts arrive at launch site for 1st flight test on June 1 (photos)

The mission was delayed May 6, two hours before launch, after an issue with the Atlas V rocket. A leak on Starliner was later discovered.

The first Boeing Starliner astronauts are back at the launch site.

NASA Crew Flight Test (CFT) astronauts Butch Wilmore and Suni Williams arrived at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Tuesday (May 28) ahead of their expected liftoff of Boeing Starliner on Saturday (June 1).

NASA will hold a delta flight readiness review later today (May 29) to review the launch, officials have said; this is a bit more detailed than a standard review, to address technical concerns on Starliner arising from a helium leak.

Assuming the mission passes that review and schedules hold, CFT will launch from the nearby Cape Canaveral Space Force Station no earlier than 12:25 p.m. EDT (1625 GMT), and you can watch the historic launch here at Space.com, via NASA Television. NASA will provide an update to reporters on Friday (May 31) at 1 p.m. EDT (1700 GMT) which you can also watch live here.

It's not the first time the crew flew in to KSC on NASA T-38 trainer jets for a launch attempt; they first flew in on April 25 for what was expected to be a May 6 launch, but that effort was scrubbed just two hours before liftoff.

As the stacked Starliner and United Launch Alliance Atlas V rocket underwent troubleshooting, the crew — still in quarantine — returned to NASA's Johnson Space Center in Houston for a few weeks to continue training and await a firmer launch date.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Starliner CFT has had a long journey to the launch pad. NASA tasked both SpaceX and Boeing with billion-dollar-scale contracts in 2014 to send astronauts to the International Space Station by 2017. Both vehicles were delayed in that goal due to technical and funding challenges.

SpaceX, borrowing from its cargo Dragon design that has flown ISS missions since 2012, finished its first crewed test in 2020. SpaceX has flown 11 other missions to the ISS since then. Starliner, a brand-new spacecraft, took longer.

Starliner's first ISS mission in 2019 without astronauts got stranded in the wrong orbit due to software glitches and failed to reach its destination. A follow-up mission in 2022 made it safely after dozens of fixes, and delays due to the pandemic.

Related: 2 astronaut taxis: Why NASA wants both Boeing's Starliner and SpaceX's Dragon

CFT met another delay in 2023 after the parachutes were found to be able to carry less load then expected, and flammable tape was found on the wiring. NASA and Starliner officials have stressed the mission is developmental — meaning not only that safety takes priority over any schedule concerns, which is true of all missions, but that course corrections will be needed as the design matures.

Both CFT astronauts are also former U.S. Navy test pilots, and thus have participated in the development of other aerospace projects over the decades.

Everything appeared on track for a May 6 launch attempt, but late in the countdown a "buzzing" valve was discovered aboard Atlas V, meaning the oxygen relief valve was opening and closing rapidly. That issue prompted ULA, Boeing and NASA to scrub the mission. Hours of troubleshooting resulted in the decision to pull the rocket back to its facility at Cape Canaveral for a valve replacement.

That valve swap went to plan by May 12, but a tiny helium leak in an Aerojet Rocketdyne thruster aboard Starliner — discovered after the scrub — then underwent close scrutiny. Team representatives told reporters in a briefing last week that they had learned a few things in that process.

The leak is not an immediate risk to a launch, since helium is an inert gas; both Crew Dragon and the space shuttle have launched safely with helium leaks, they noted. The concern is how that leak would affect the reaction control system (RCS); that is a set of 28 small engines aboard Starliner for modest maneuvers in orbit.

The leak is in a button-sized area in the Starliner spacecraft less than 10 sheets of paper thick, in a rubber seal between two metal parts of a flange. The leak is roughly 50 psi to 70 psi depending on the pressurization around it, but that (apparently) high rate is relative to a tiny space, NASA and Boeing stressed in the briefing.

It was unsafe to open up this spot with Starliner stacked on Atlas V, but extensive computer analysis showed the leak appeared to be stable. The team did pressure changes on this area as well, to simulate changes in spaceflight, and were satisfied with the performance they saw.

Additionally, the other 27 thrusters have no leak at all, creating a large buffer if other leaks arise, NASA's Steve Stich, program manager for the agency's commercial crew program, emphasized in the May 24 call.

He added that engineers, however, uncovered a "design vulnerability" during the helium troubleshooting. Simply put, Starliner has three certified modes of returning the astronauts to Earth: One mode using the RCS thrusters, and two modes using orbital maneuvering and attitude control (OMAC) thrusters; the OMAC modes require two or four of those thrusters, depending on the situation.

The RCS re-entry mode requires eight thrusters in adjacent "doghouses:" There are four of these assemblies around Starliner. But under rare helium leak circumstances, it may be that all thrusters in adjacent doghouses could fail simultaneously, meaning RCS would not be available any more to back up OMAC. The team thus created, and simulated with the CFT astronauts, a new re-entry mode that would require only four RCS thrusters at a time. The delta flight readiness review will confirm the certification of that new re-entry technique, among other matters.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.