A Churning 'Molten Blob' of Planet May Be Easier to Find. Here's Why.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The smaller a planet, the more difficult it is to spot — which is frustrating for scientists hoping to find Earth-like worlds.

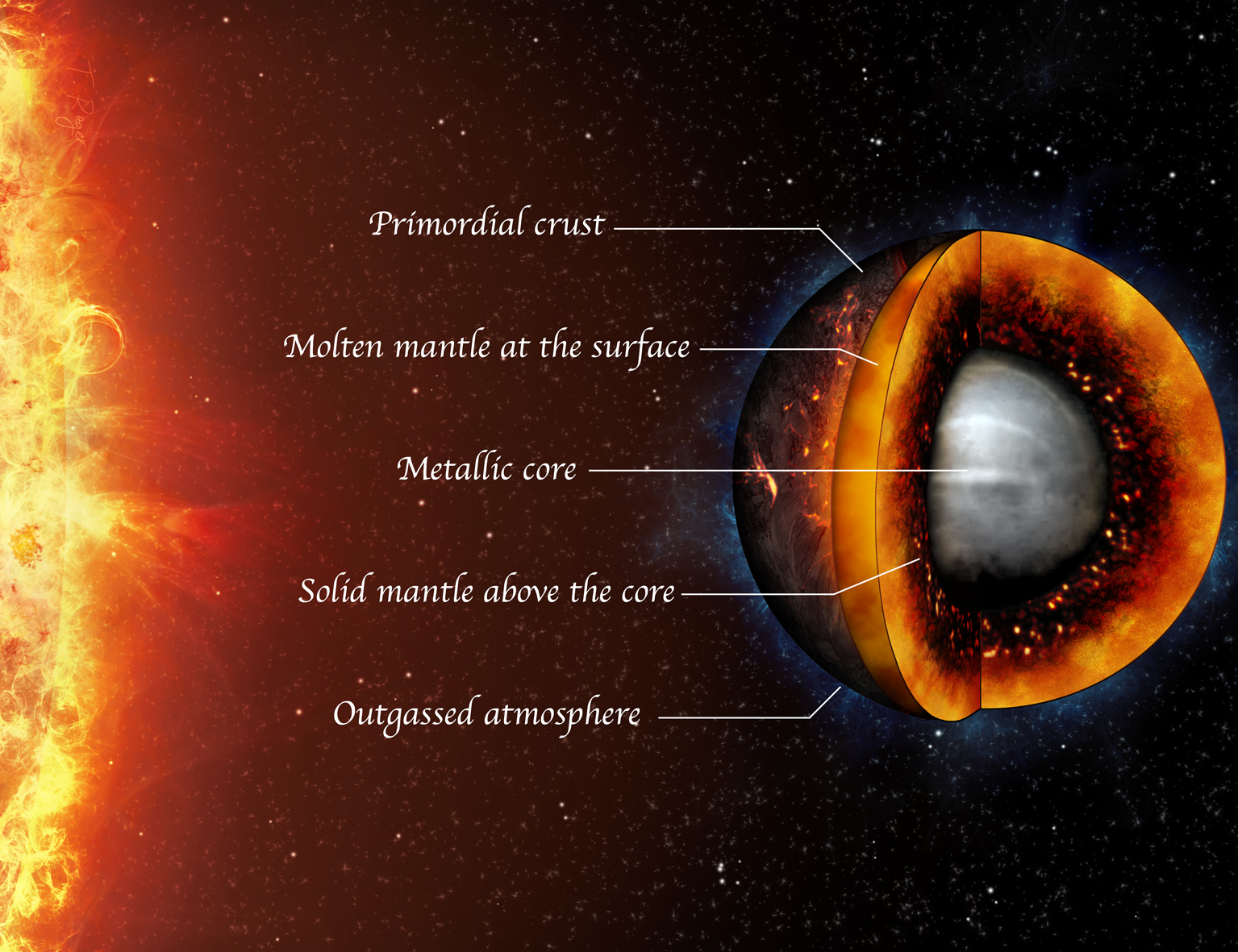

That's why a team of researchers set out to determine what planetary traits would make a world a little easier to identify. Their analysis suggests that molten worlds with atmospheres full of water or carbon dioxide will be more easily observed by instruments that will be available to scientists soon.

"A rocky planet that is hot, molten and possibly harboring a large outgassed atmosphere ticks all the boxes," Dan Bower, lead author on the new study and an astrophysicist at the University of Bern, said in a statement. "Granted, you wouldn't want to vacation on one of these planets, but they are important to study since many if not all rocky planets begin their life as molten blobs, yet eventually some may become habitable like Earth."

Related: The Most Fascinating Exoplanets of 2018

Earth grew out of its molten stage pretty quickly, but other worlds may retain a so-called magma ocean in which much of the planet's surface is churning lava. Bower and his colleagues wanted to consider this stage of a rocky planet's life because molten rock is a little less dense than solid rock.

And that's a boon for observers: If two planets have the same mass but one has a magma ocean and the other doesn't, it could be about 5% larger across, making it easier to spot. And a molten world is more likely to be leaking water and carbon dioxide from that liquid rock out into a developing atmosphere.

Those two molecules are easily released by molten rock, but they are also the sort of thing that future telescopes like NASA's James Webb Space Telescope are being designed to detect. Webb won't be able to study Earth-size planets around stars like our sun, but it should be able to analyze those around smaller M dwarf stars.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Similarly, the slightly larger size of these molten planets won't help the struggles of finding planets orbiting sun-like stars. But the European Space Agency's CHEOPS exoplanet-hunting mission, which is due to launch late this year, should be able to measure differences in size at that scale around M dwarf stars.

And if scientists can study such planets, they'll learn about more than just these distant worlds. "Clearly, we can never observe our own Earth in its history when it was also hot and molten," Bower said. "Thinking about Earth in the context of exoplanets, and vice-versa, offers new opportunities for understanding planets both within and beyond the solar system."

The research is described in a paper being published in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics. You can read a copy of the paper on the preprint server arXiv.org.

- 7 Ways to Discover Alien Planets

- Photographing an Exoplanet: How Hard Can it Be?

- The Strangest Alien Planets in Pictures

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.