These Glass Pearls from Clam Fossils Hint at Ancient Meteorite Crash in Florida

Tiny glass pearls found inside fossilized clams are likely a sign that a meteorite made a sizeable splash near the ancient Florida peninsula, according to a team of researchers.

The place where these ancient clams were found in 2006 now lies underneath a housing development — "Such is the nature of Florida," Mike Meyer, the lead researcher who found these glass beads, said in a recent statement about the cosmic marbles. But the Sarasota County site was once a quarry where undergraduates conducted summer field work under the tutelage of Roger Portell, invertebrate paleontology collections director at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

It was there that Meyer, then a student at the University of South Florida, came across the small spherical objects. According to a museum statement published Monday (July 22) about the recent analysis of these objects, Meyer had 83 of them tucked away for over a decade in a box because no one he contacted knew what they were.

Related: What Are Meteorites?

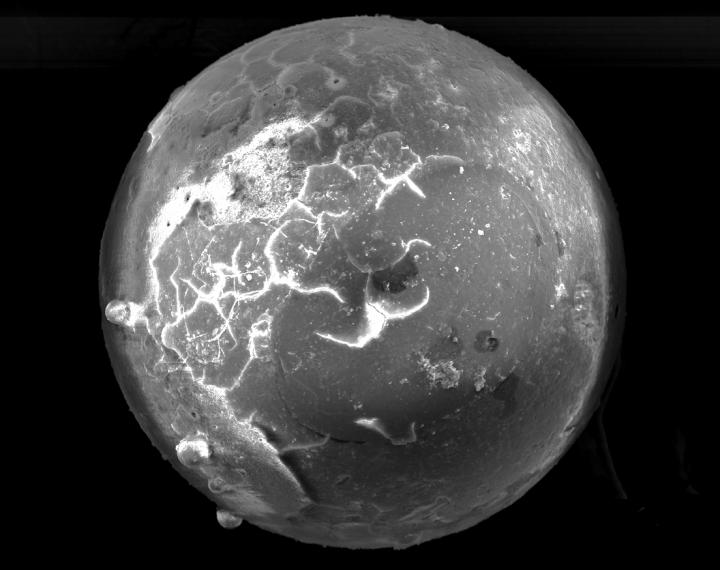

Meyer was surprised when he finally analyzed them and found that they are likely Florida's first known case of microtektites, or what's left when streamers of molten material shoot off, become rounded and harden in the aftermath of a meteorite strike.

The glassy and translucent "microspherules" are fascinating for several reasons.

They reveal signs of a previously unknown impact event, for starters. According to the study, Meyer found evidence that they're probably the by-products of one or more small ancient bombardments that happened on or near the plateau upon which the Florida Peninsula sits, known as the Florida Platform. The high level of sodium found within them indicates that ocean water may have splashed at high pressure near where the clams were living at the time, thereby encrusting them with this seawater element.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The clean spherical shape of these mini-meteorite pearls were also dazzling and a giveaway to an extraterrestrial origin, according to Meyer. "Sand grains are kind of lumpy, potato-shaped things," he said in the statement. "But I kept finding these tiny, perfect spheres." And an unpublished test suggests the microspherules also have traces of metals rarely seen on Earth, according to the statement.

The microtektites also highlight how fossil clams can be natural time capsules from ancient Earth.

Meyer and Portell, who is a co-investigator of the recent study, were working around an ancient seabed of clams that closed their shells tightly when they died, keeping objects that had washed in preserved over time. It's not just the messy impact leftovers that clam shells have preserved over millions of years: These hard shells from the ancestors to modern southern quahogs — which boast curved, dingy-white shells and belong to the family of venus clams — have trapped crab and fish bones too, according to Portell.

Further testing will be needed to confirm the findings, but for now, Portell's working guess is that these microtektites date back 2 or 3 million years.

A paper detailing the team's work was published May 6 in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science.

- Rare Comet Fragment Found Inside Rocky Meteorite

- Biggest Meteorite Impact in the UK Found Buried in Water and Rock

- This Weird Meteorite Crashed Through a Doghouse in Costa Rica. (The Dog's Fine)

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.