This Weird Meteorite Crashed Through a Doghouse in Costa Rica. (The Dog's Fine)

A "ruff" wake-up call for Rocky.

Rocky was napping in a doghouse in Costa Rica on April 23 when a small meteorite punctured the roof. The dog was unharmed, but couldn't hope to match scientists' interest in fetching the stray meteorite.

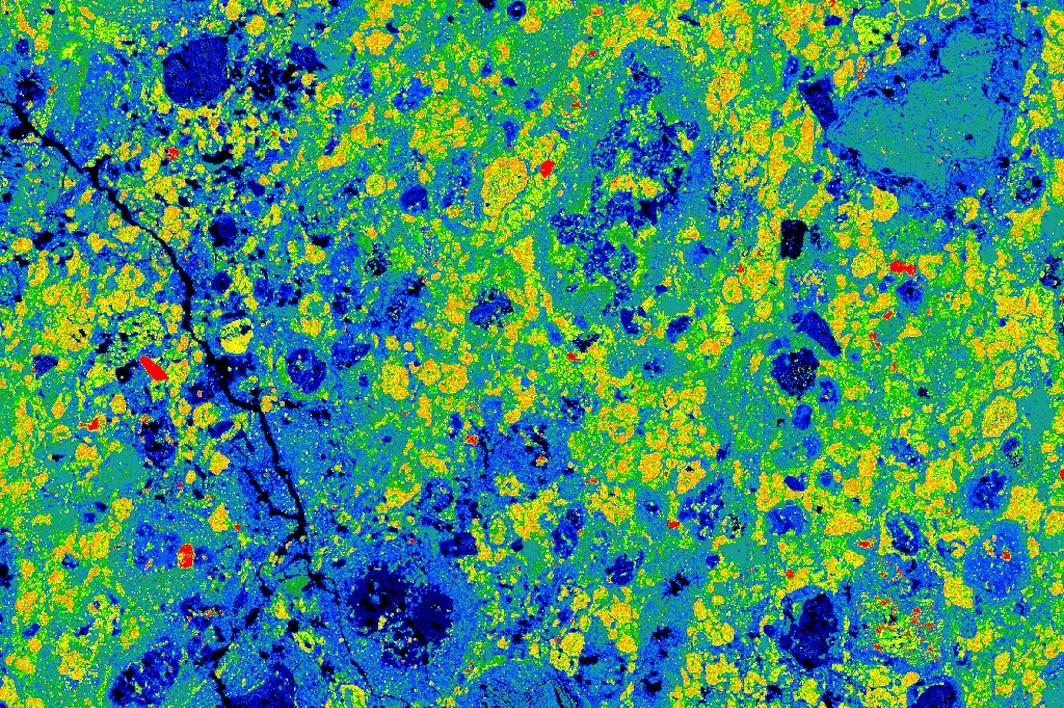

That's because Rocky's space rock was just one piece of a clay-rich meteorite that crashed to Earth over the town of Aguas Zarcas in Costa Rica. Clay-rich meteorites are scientifically fascinating, preserving water-rich minerals from beyond Earth. But they're also fragile: Rain can cause this type of meteorite to fall apart. Hence scientists' enthusiasm over Rocky's sample and other fragments of the meteorite, which they estimate was about the size of a washing machine when it entered Earth's atmosphere.

"It formed in an environment free of life, then was preserved in the cold and vacuum of space for 4.56 billion years, and then dropped in Costa Rica last week," Laurence Garvie, a curator at Arizona State University's Center for Meteorite Studies, said in a statement. "Nature has said 'here you are,' and now we have to be smart enough to tease apart the individual components and understand what they are telling us."

Related: Photo Gallery: Images of Martian Meteorites

Garvie and his colleagues are now working to do just that, analyzing fragments collected in the five days after the Aguas Zarcas meteorite fell last month. (Those days were all dry, preventing rain from eating away at the meteorites.) In addition to analyzing them, the team also needs to protect them, which researchers do by placing the space rocks in nitrogen cabinets that preserve them.

"If you left this carbonaceous chondrite in the air, it would lose some of its extraterrestrial affinities," Garvie said. "These meteorites have to be curated in a way that they can be used for current and future research."

Because the Aguas Zarcas meteorite was a carbonaceous chondrite, it was mostly clay, prompting Garvie to describe it as a mud ball. The high clay content means that scientists may be able to use these meteorites to better understand how humans could one day pull water out of asteroids to turn into drinkable water or rocket fuel.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But the meteorites are also scientifically interesting, since they should contain trace information about the earliest days of the solar system, when all this cosmic rubble first formed.

"Carbonaceous chondrites are relatively rare among meteorites but are some of the most sought-after by researchers because they contain the best-preserved clues to the origin of the solar system," Meenakshi Wadhwa, who leads the meteorite center, said in the same statement.

- Black Glass in New Martian Meteorite (Photos)

- Powerful Bering Sea Fireball Spotted from Space in NASA Photos

- Photos: Russian Meteor Explosion of Feb. 15, 2013

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.