Mercury flyby tonight: Europe's BepiColombo spacecraft to attempt its 1st swing past the planet

It will be the closest look at Mercury for BepiColombo of its entire mission.

A spacecraft bound for the planet Mercury will take a first look at the target tonight, when it makes its first-ever flyby of the small rocky world during an incredibly close encounter tonight.

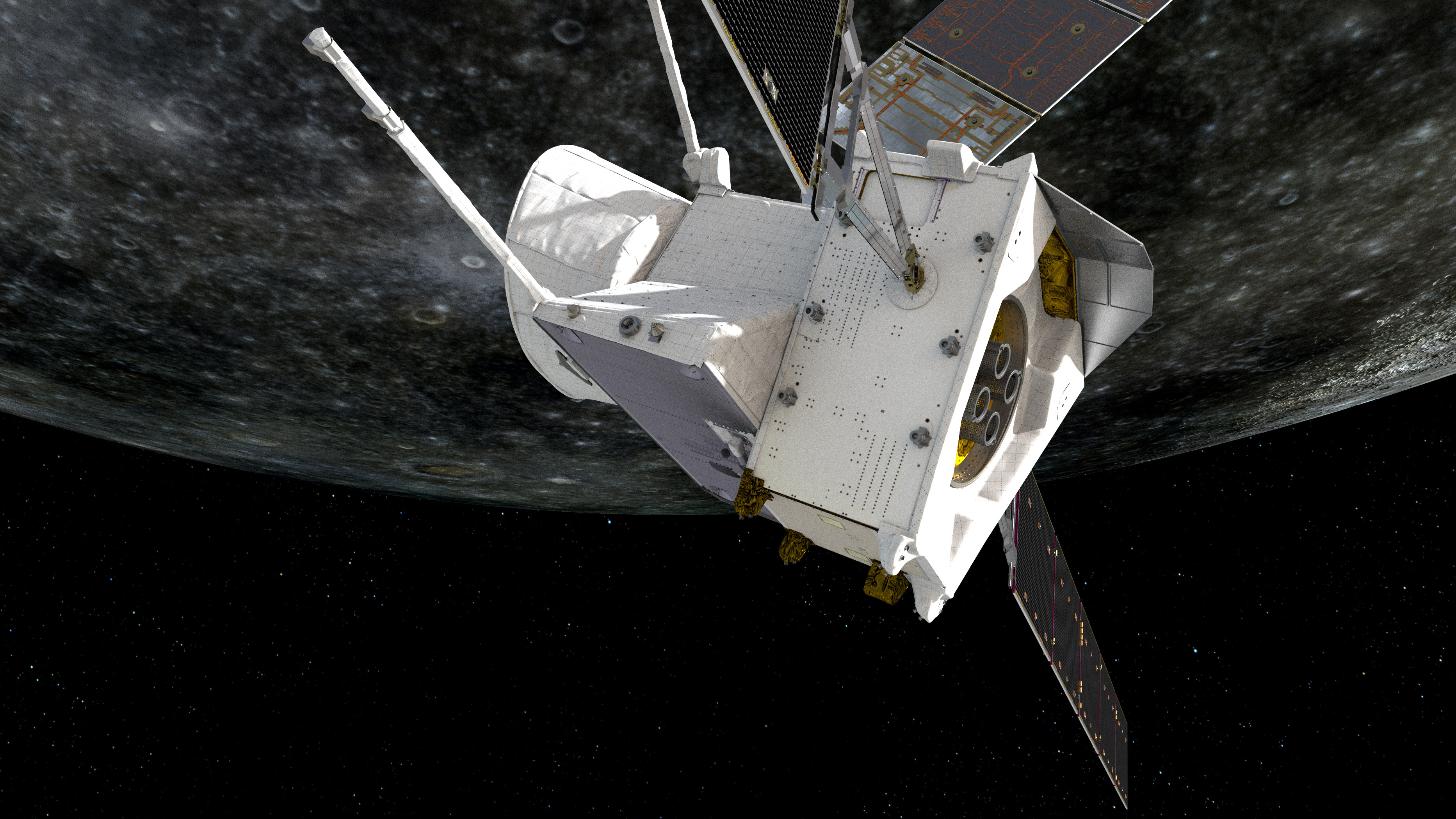

The mission, called BepiColombo, is a joint project of the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). It is only the second mission in history sent to orbit Mercury, the smallest and innermost planet of the solar system.

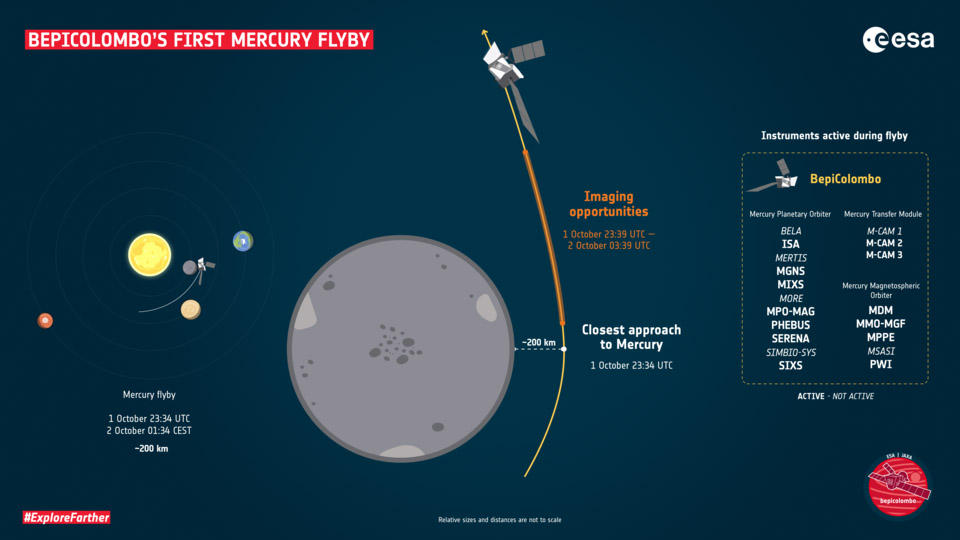

BepiColombo's flyby tonight (Oct. 1) will bring the spacecraft within just 124 miles (200 kilometers) of the surface of Mercury, the closest the probe will ever get to the planet during its mission. The first images from the encounter are expected to reach Earth early Saturday (Oct. 2) and will be the first close images of Mercury's scorched surface since the end of NASA's Messenger orbiter mission in 2015.

Related: BepiColombo spacecraft documents 1st year in space with selfies

BepiColombo will make its closest approach to Mercury at 7:34 p.m. EDT (2334 GMT) today (Oct.1), ESA said in a statement. The spacecraft will then continue on its winding trajectory around the sun.

This close pass is one of nine gravity-assist flybys, maneuvers that use the gravity of celestial bodies to adjust a spacecraft's trajectory, that BepiColombo needs to perform before it can enter its target orbit around the planet. This flyby, however, will take the spacecraft even closer to the scorched planet's surface, than its ultimate scientific orbit of 300 to 930 miles (480 to 1,500 kilometers).

Unfortunately, BepiColombo won't be able to use all of its instruments during this opportunity as it is still in its transit configuration. The spacecraft consists of two orbiters, ESA's Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO) and JAXA's Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter, that will eventually circle the planet separately. The two orbiters are stacked on top of a transfer module, which blocks some of their instruments, including a high-resolution camera.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mercury selfie time!

The €650 million ($750 million) BepiColombo mission will be able to make measurements of the environment around the planet and take images with its black and white 'selfie' cameras, which provide a 1024 by 1024 pixel resolution (comparable to an early-2000s flip phone.)

Originally designed to monitor the unfolding of the spacecraft's solar panels after its launch in October 2018, these selfie cameras previously obtained images of Earth and Venus during earlier BepiColombo flybys. During the Earth flyby in April 2020 and the first Venus flyby in October of that year, BepiColombo zipped by the planets at much greater distances of 7,900 miles (12,700 kilometers) and 6,650 miles (10,700 km) respectively. The second Venus flyby in August of this year took BepiColombo as close as 340 miles (550 kilometers) to the planet's surface. However, due to Venus' high reflectiveness, the images were overexposed and didn't reveal any detail.

Will we spot Mercury's mysterious hollows?

BepiColombo project scientists at ESA Johannes Benkhoff told Space.com in an August interview that he expected Mercury to provide a much better photo opportunity than the probe's past flybys. The spacecraft will be incredibly close to the planet's surface and Mercury is dark, unlike Venus, so there should not be any overexposure problems.

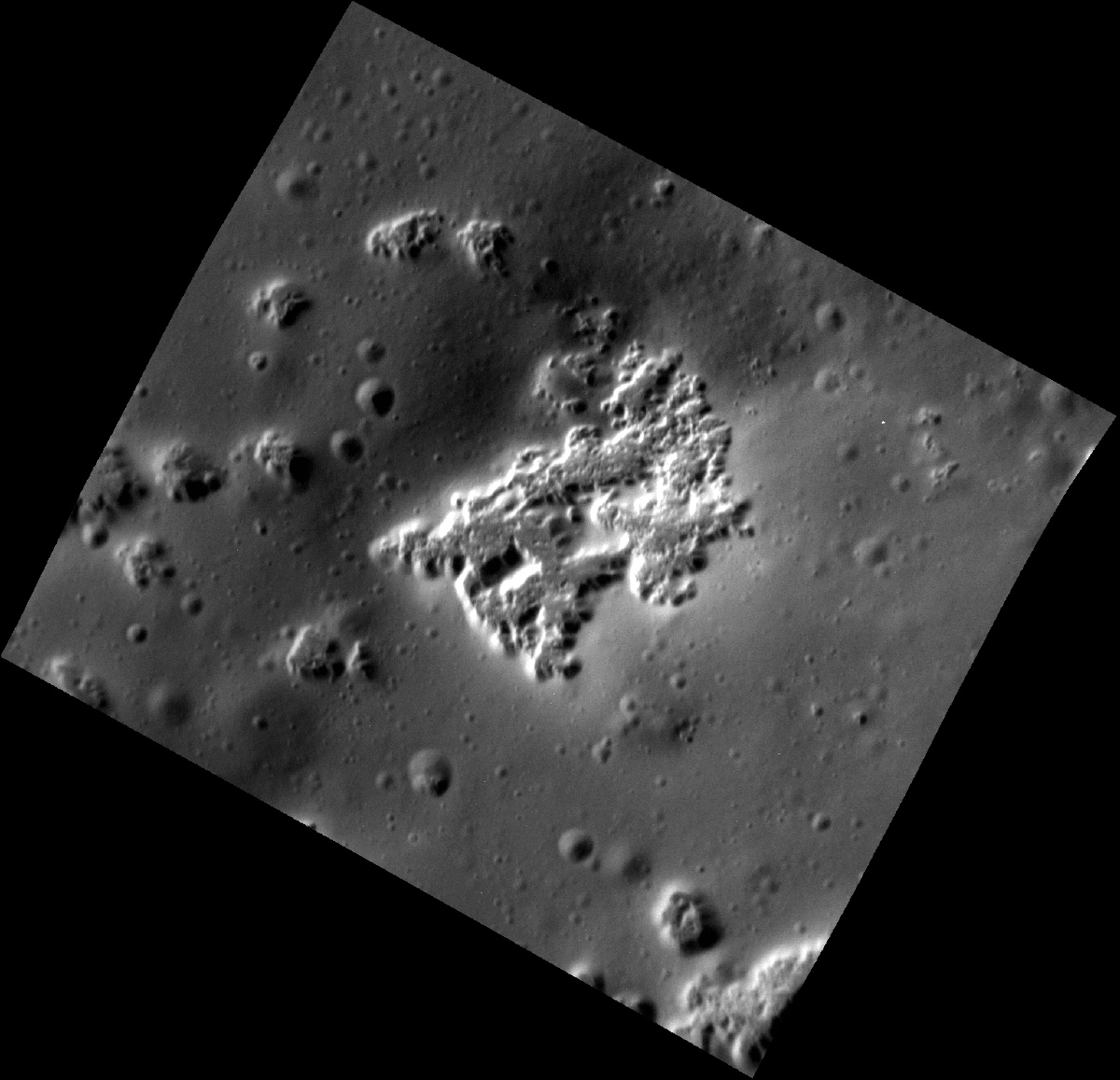

"We hope that even with our selfie cameras, we may identify some structures on the surface of Mercury," Benkhoff said.

The team would be particularly keen to spot the so-called hollows on Mercury, mysterious dents on the planet's surface first discovered by NASA's Messenger probe. Not seen on any other planet in the solar system, these hollows might be caused by evaporation of material from inside Mercury, scientists believe, and might be an indication that the moon-sized planet is much more active than previously thought.

"The interesting thing is that these hollows appear to be fairly recent," Benkhoff said in an ESA statement. "It appears that there is some volatile material coming up from the outer layer of Mercury and sublimating into the surrounding space, leaving behind these strange features."

Still four years to go

After tonight's close pass, it will take four more flybys of Mercury by BepiColombo before the spacecraft is in the correct position to finally enter the planet's orbit, which is set to happen in 2025.

Mercury's orbit is notoriously difficult for a spacecraft to reach. Although Earth is on average ten times closer to Mercury than to Jupiter, missions aiming for orbits around those planets take about the same time. The reason for that is that a mission to Mercury needs to constantly brake against the gravitational pull of the sun.

The spacecraft could brake using its thrusters, but the amount of fuel it would need would make such a mission technically nearly impossible. The spacecraft therefore follows a much longer route that takes advantage of the gravitational pull of celestial bodies to gradually slow down.

A mission to Mercury has some extra technical hurdles to overcome. Orbiting at about a third of the sun-Earth distance, Mercury is extremely hot. The two BepiColombo orbiters will have to handle temperatures of nearly 932 degrees Fahrenheit (500 degrees Celsius), which would melt conventional spacecraft solar panels, ESA said in a statement.

BepiColombo's next flyby at Mercury will take place in June 2023. Four additional flybys at the planet will follow, none as close as the one today. In December 2025, the spacecraft will be finally ready to enter Mercury's orbit. The two orbiters will then separate and each will start its own scientific investigation.

Full of mysteries

It will probably be only after the BepiColombo orbiters begin their separate missions in orbit above Mercury that scientists will learn more about the nature of the planet's surface hollows. By that time, 10 years will have passed since the demise of Messenger, and the teams hope they will be able to compare high-resolution images from both spacecraft and detect changes on the surface.

"If we prove that these hollows are changing, that would be one of the most fantastic results we could get with BepiColombo," Benkhoff said in the statement. "The process driving the creation of these hollows is totally unknown. It might be caused by heat or by solar particles bombarding the surface of the planet. It's something completely new and everyone is looking forward to getting more data."

But there are other fascinating questions about the small seemingly lifeless planet at the heart of our solar system. In spite of the scorching temperatures, Mercury seems to harbor ice in shaded craters around its poles. It also has a magnetic field, which scientists would not expect it to have due to its small size. Scientists are also puzzled by the planet's chemical composition, which suggests it may not have formed this close to the sun but may have been thrown there by a violent cosmic collision. Many questions to answer for BepiColombo, and tonight's flyby is set to provide only the tiniest taster of the science to come.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.