James Webb Space Telescope spots faint galaxy 'PEARLS' in stunning new view

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

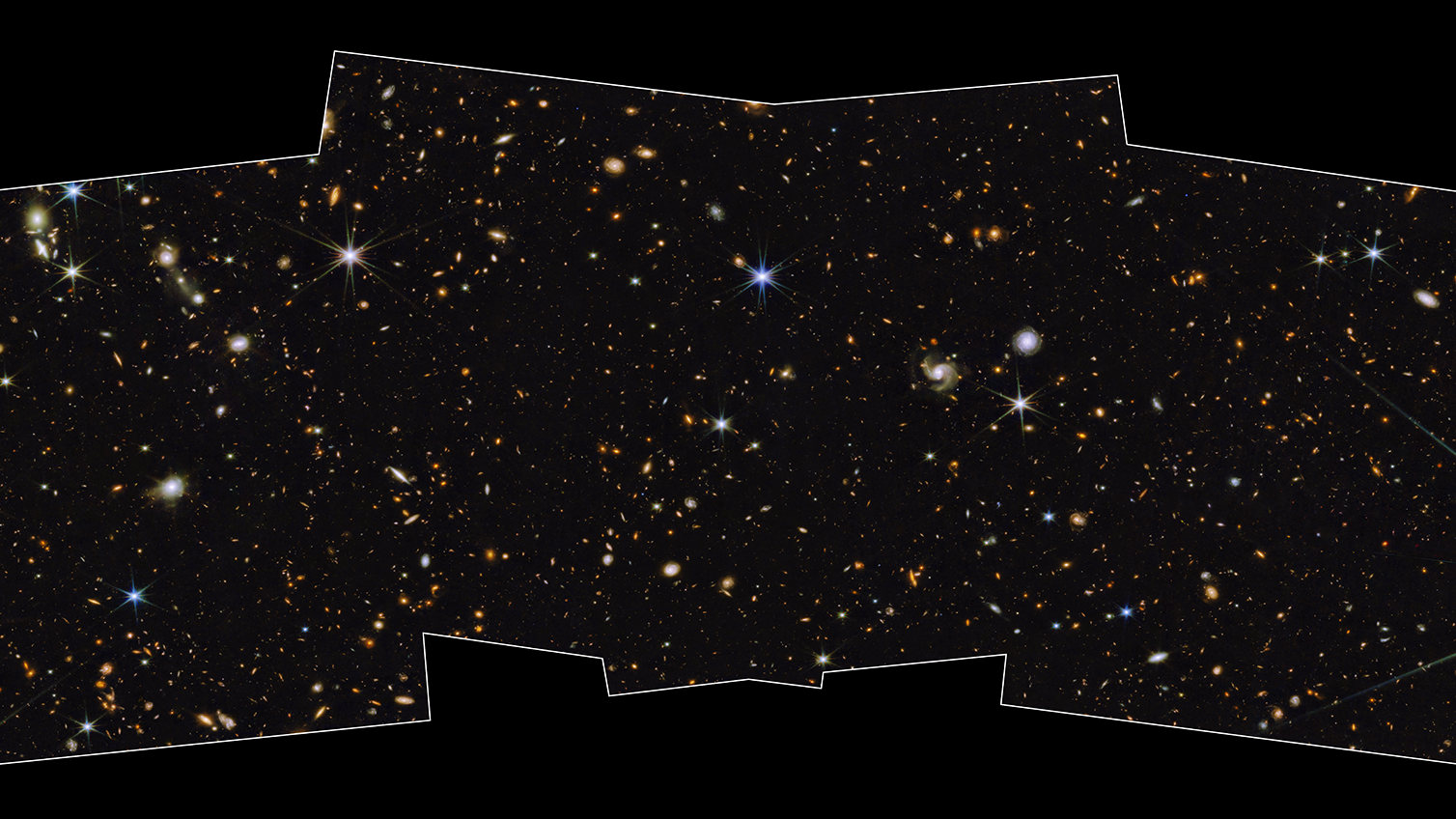

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope continues to amaze, this time with an exquisite image revealing previously unseen galaxies in an area known as the North Ecliptic Pole.

The image is one of the few medium-deep, wide-field images of our cosmos and shows thousands of galaxies across a bewildering range of distances, stretching to the farthest reaches of the universe, while also being studded with stars from our own Milky Way. The new James Webb Space Telescope (Webb or JWST) image, which comes from the Prime Extragalactic Areas for Reionization and Lensing Science (PEARLS) program, also highlights a number of interacting galaxies.

"I was blown away by the first PEARLS images," Rolf Jansen, an astronomer at Arizona State University and a PEARLS co-investigator, said in a statement.

"Little did I know, when I selected this field near the North Ecliptic Pole, that it would yield such a treasure trove of distant galaxies, and that we would get direct clues about the processes by which galaxies assemble and grow," he said. "I can see streams, tails, shells, and halos of stars in their outskirts, the leftovers of their building blocks."

Gallery: James Webb Space Telescope's 1st photos

Webb's Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) captured the sparkling scene, which covers a patch of sky measuring 2% of the area covered by the full moon. The image was constructed using eight different colors of near-infrared light collected by NIRCam, augmented with three colors of ultraviolet and visible light from the Hubble Space Telescope.

"Medium-deep" refers to the faintest objects that can be seen in this image, which are about 1 billion times fainter than what can be seen with the unaided eye, according to a NASA statement. The PEARLS program focuses on the gravitational lensing of objects in the background of galactic clusters; these clusters are so massive that they warp space-time, magnifying the light from objects behind them.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The location of this particular field of sky, at the north ecliptic pole, means it can also be monitored at any time of the year and not be blocked by the sun as JWST orbits. Regular views mean JWST can see what pops up in the field, promising opportunities for time-domain astronomy, which focuses on how astronomical objects change with time.

"Such monitoring will enable the discovery of time-variable objects like distant exploding supernovas and bright accretion gas around black holes in active galaxies, which should be detectable to larger distances than ever before," Anton Koekemoer, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Maryland, which operates JWST, and a PEARLS team member, said in the statement.

The research is described in a paper published Wednesday (Dec. 14) in the Astronomical Journal.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Andrew is a freelance space journalist with a focus on reporting on China's rapidly growing space sector. He began writing for Space.com in 2019 and writes for SpaceNews, IEEE Spectrum, National Geographic, Sky & Telescope, New Scientist and others. Andrew first caught the space bug when, as a youngster, he saw Voyager images of other worlds in our solar system for the first time. Away from space, Andrew enjoys trail running in the forests of Finland. You can follow him on Twitter @AJ_FI.