India Says Its Anti-Satellite Weapon Test Created Minimal Space Debris. Is That True?

"Mission Shakti" raises questions.

Just weeks before election season starts in India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the nation completed a successful test-fire of its first anti-satellite launch missile, dubbed "Mission Shakti," on Wednesday (March 27). The event sparked a global conversation about space policy, politics and the militarization of space in the hours that followed, as well as speculation about whether that type of test could create dangerous space debris.

This achievement by India's Defence Research and Development Organisation (DDRO) and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) makes it only the fourth country to ever launch an anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon.

"The test was done in the lower atmosphere to ensure that there is no space debris," officials from India's Ministry of External Affairs said in a statement. "Whatever debris that is generated will decay and fall back onto the earth within weeks."

Related: Space Junk: Tracking & Removing Orbital Debris

The contents of Modi's address to the nation were unexpected. There was intense speculation about what his message might be about after Modi tweeted an advisory of the announcement, which was scheduled for about noon local time.

An anti-satellite weapon is anything that destroys or physically damages a satellite. According to SpaceNews, the only other countries that have fired an ASAT are the United States, Russia and China.

#MissionShakti was a highly complex one, conducted at extremely high speed with remarkable precision. It shows the remarkable dexterity of India’s outstanding scientists and the success of our space programme.March 27, 2019

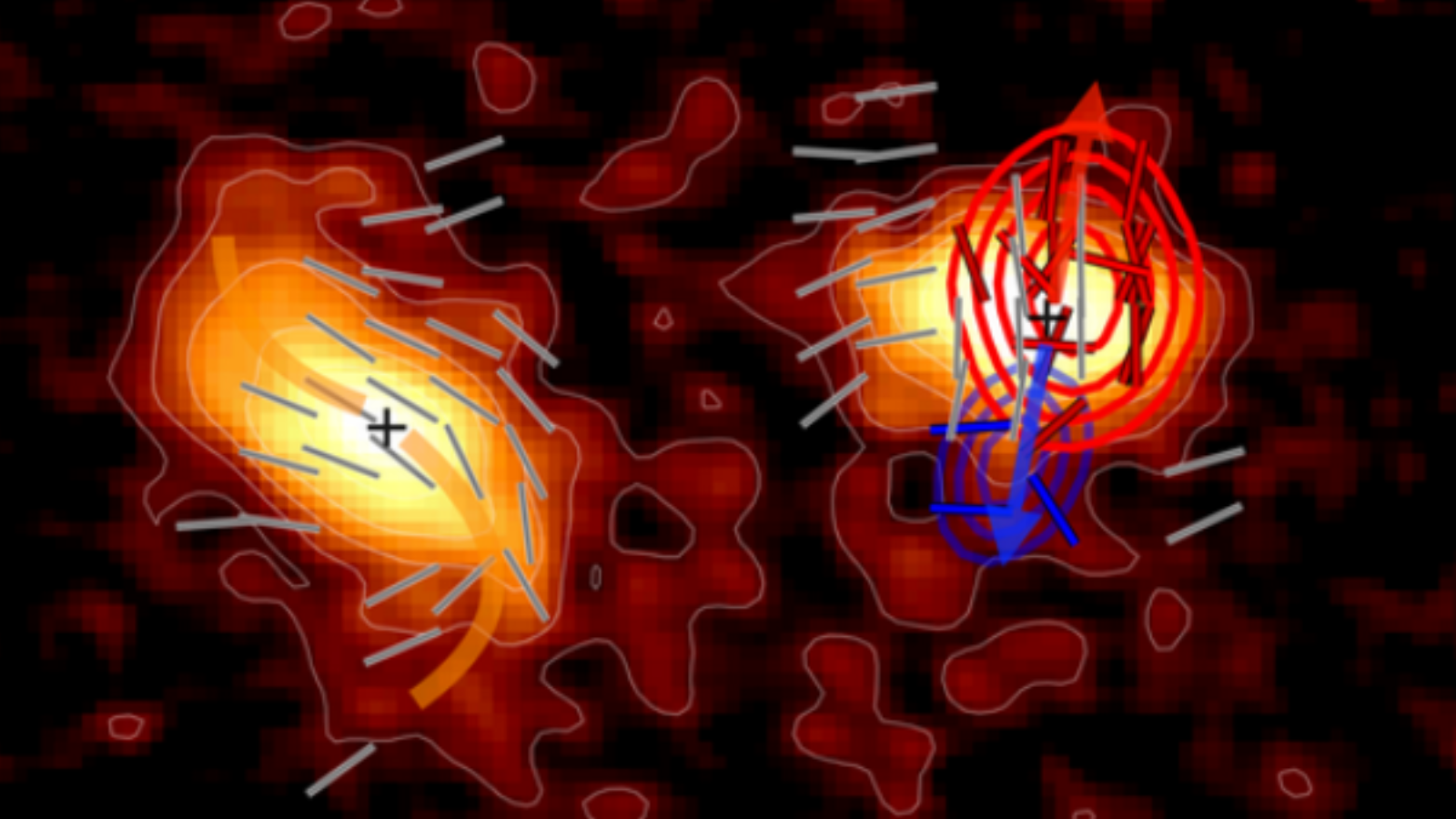

Most outlets confirmed the satellite target was an Indian spacecraft in low Earth orbit called Microsat-R, according to astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell at the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The satellite target was at an altitude of about 168 miles (270 kilometers), McDowell told Space.com, and was passing northbound over the Bay of Bengal when the ASAT intercepted it.

The launch missile "doesn't carry any explosive, but just puts itself in the path of the satellite," McDowell said. "The satellite is traveling at 18,000 mph (29,000 km/h) … the kinetic energy of that impact is much more than any high explosive you could carry, so no point in putting a bomb on it."

The impact "would have sent a hypersonic shock wave through the Microsat-R satellite and reduced it to shrapnel," McDowell said. And after a few weeks it ought to burn up in Earth's atmosphere.

"What we are expecting is that U.S. space tracking will catalog a bunch of new debris objects; that has not happened yet… before you can actually catalog the debris, it may take several days to actually sort out and see how many individual objects you have, and not double count things," he said.

Unlike China's ASAT launch in 2007, which struck their Fengyun-1C weather satellite resulting in severe fragmentation and long-lived debris, McDowell believes the orbital zone of Microsat-R means most of the shrapnel here will likely burn up in Earth's atmosphere over the next three weeks. But some may stay up for about a year.

Microsat-R was at a lower altitude than Fengyun. It was at about the same altitude as the satellite USA 193, which was the target of a U.S. anti-satellite test called Operation Burnt Frost in February 2008, according to Space News. USA 193 was about 155 miles (250 km) high at the time of impact. Unlike Mission Shakti, the U.S. government announced Burnt Frost in advance.

ISRO is the space agency of the government of India, and has its headquarters in the city of Bengaluru. DRDO carries out military research and development for the Indian government, and is based in New Delhi.

Editor's Note: This article was updated to clarify McDowell's thoughts on how long debris might persist in orbit.

- U.S. Official: China Turned to Debris-free ASAT Tests Following 2007 Outcry

- China, Russia Advancing Anti-Satellite Technology, US Intelligence Chief Says

- Worst Satellite Breakups in History: We're Still Feeling Effects

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.