One-of-a-Kind Copy of Galileo's Book That Upended the Earth-Centric View of the Universe Was a Fraud.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

An exceptionally rare and valuable copy of a 17th-century book by Galileo Galilei — seemingly signed and hand-illustrated by the great astronomer and thinker — was hailed as the find of the century when it was unveiled in 2005 by a respected bookseller in New York City.

But within a few years, an avalanche of evidence proved that the book was a clever forgery.

How was the counterfeit copy able to fool respected antiquarians, and what led to the discovery that the tome was a fake? The fascinating story is recounted in "Galileo's Moon," a PBS documentary that aired July 2. [Faux Real: A Gallery of Forgeries]

Astonishing find

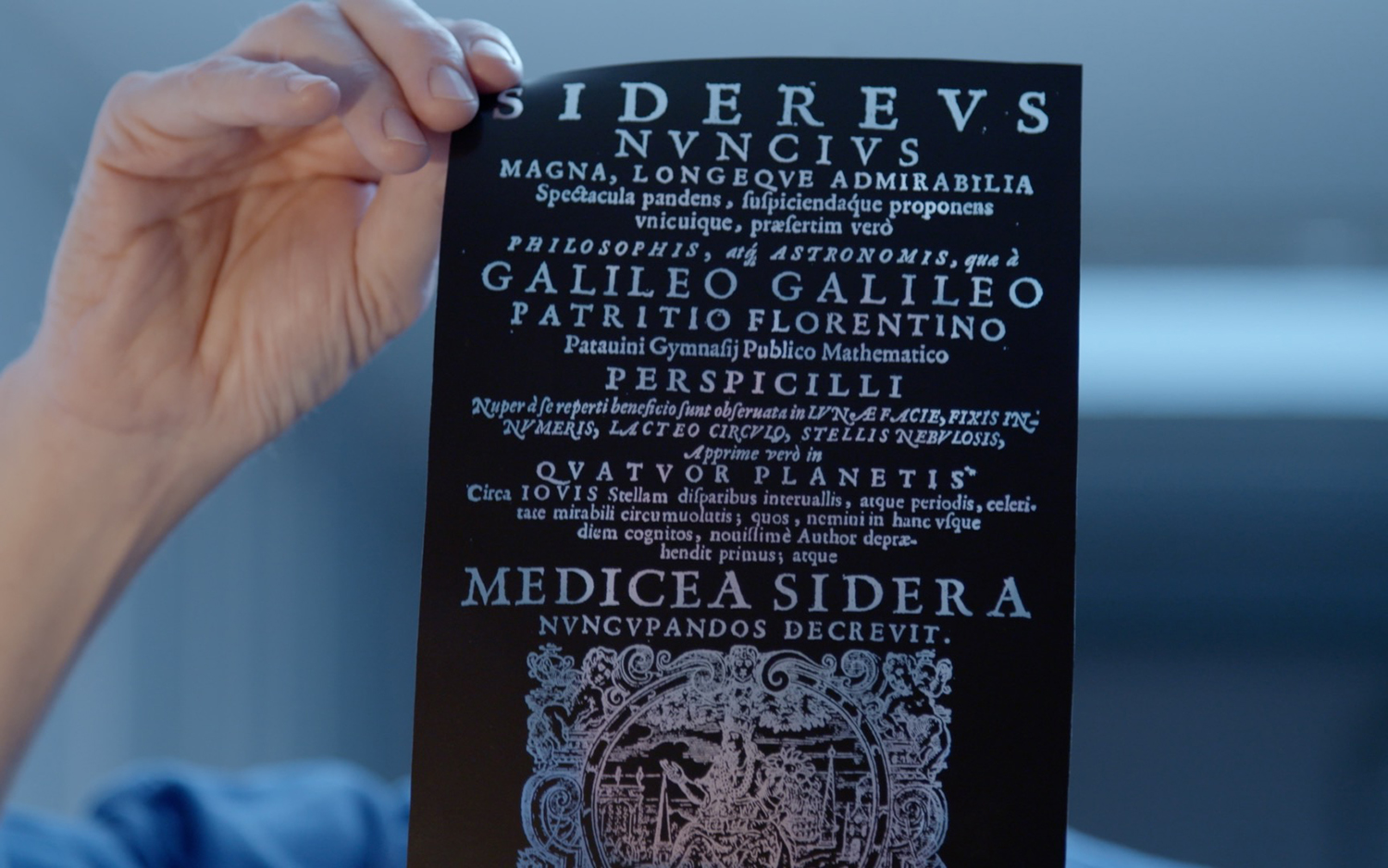

In 2005, historians were floored by the discovery of a one-of-a-kind book — a purported "proof" of Galileo's "Sidereus Nuncius," also known as "Starry Messenger." Published in 1610, the book established Galileo's reputation as the foremost astronomer of his day; 550 copies of the book were printed, of which 150 known copies remain, PBS representatives said in a statement.

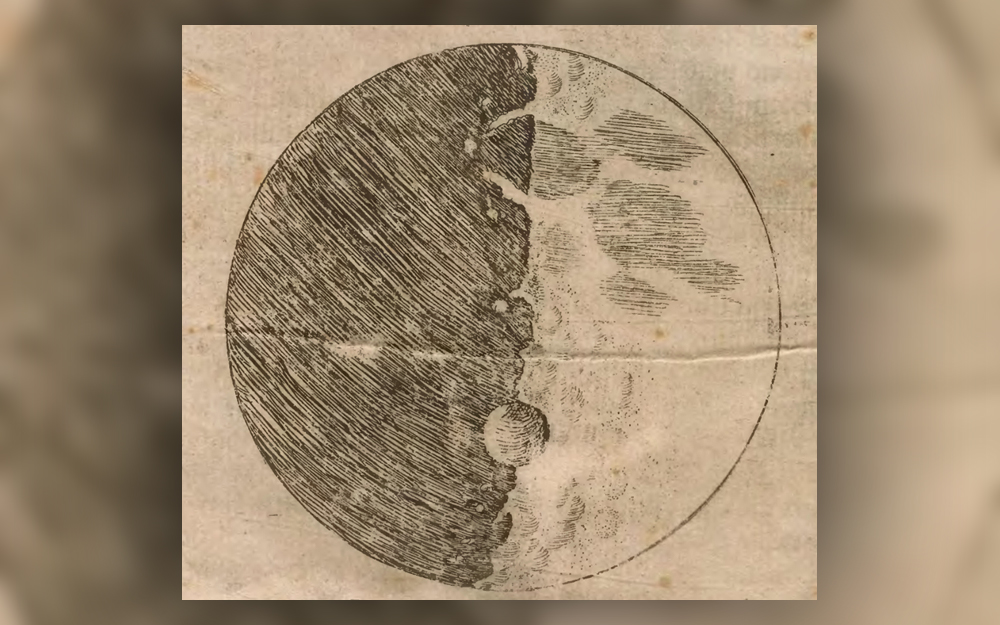

"Sidereus Nuncius" was the first work to show that the lunar surface was mountainous and pocked, and Galileo's observations of four satellites orbiting Jupiter were even more astounding. These "Medicean stars," as Galileo called them in the book's title page, were "unknown by anyone until this day," and they upended the current scientific view of Earth as the center of the universe.

Too good to be true

Any "lost" copy of this book would have been a major find. But this copy was also signed by Galileo and bore a stamp from the library of Rome's Lincean Academy, where Galileo was a member. And while other copies of "Sidereus Nuncius" included four engravings of the moon's phases, this version had watercolors, purportedly painted by Galileo himself, according to PBS.

Books from the 17th century were thought to be near-impossible to forge because of how they were printed, with the metal type assembled one character at a time and the pages pressed by hand.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

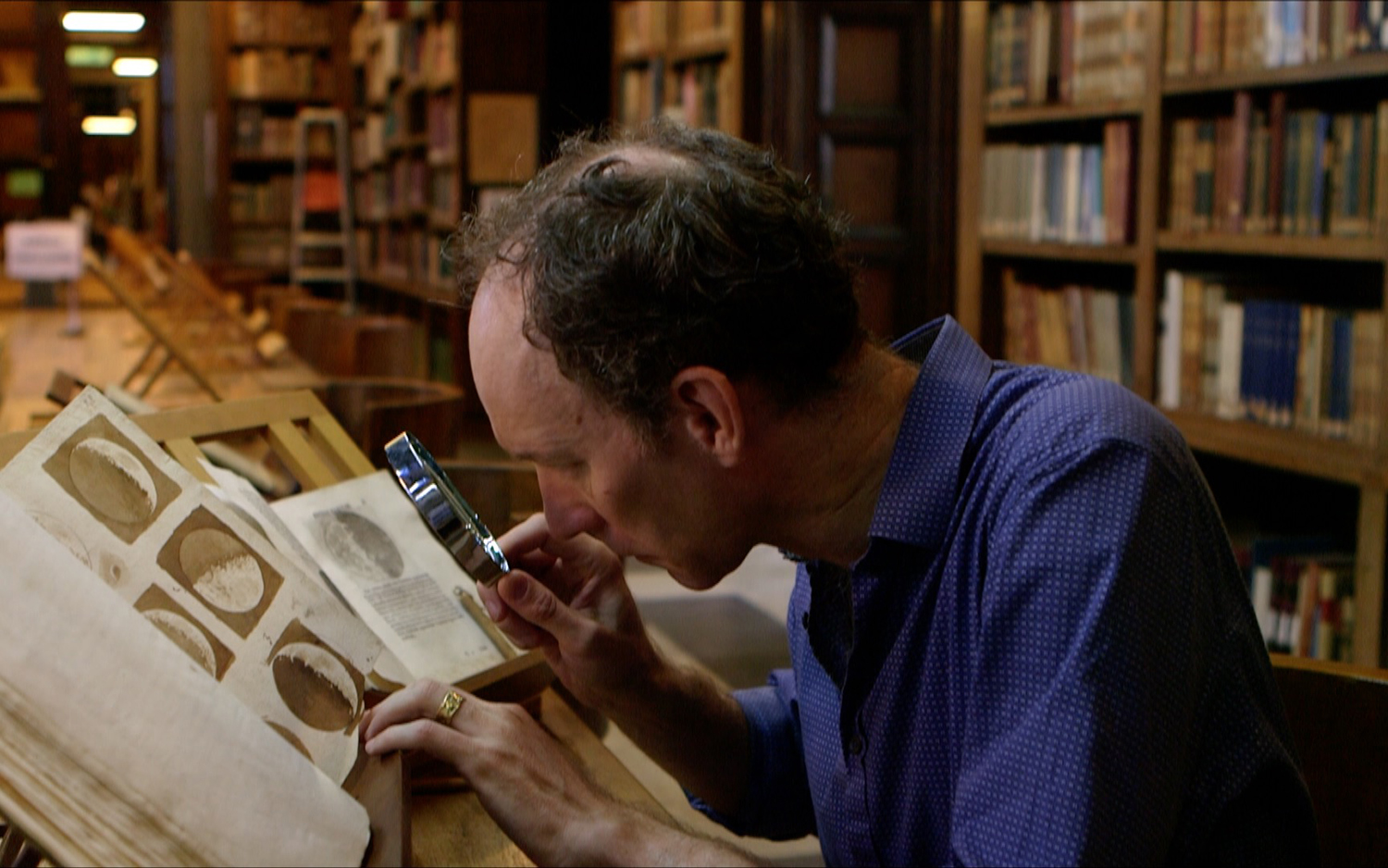

But though the book's physical details appeared genuine, its provenance was light on details, which should have sounded alarm bells for the team confirming the book's authenticity, said Nick Wilding, a Galileo scholar and professor of history at Georgia State University, who examined the book. Then in 2012, police in Italy arrested a man named Marino Massimo De Caro, former director of the Girolamini Library in Naples, on suspicion of stealing and selling thousands of books from the library's collection.

De Caro was one of the people who sold the illustrated "Sidereus Nuncius" copy to the antique-book dealer Martayan Lan, Wilding told Live Science. With De Caro as the book's source, its legitimacy was immediately suspect; it could have been stolen or doctored. [30 of the World's Most Valuable Treasures That Are Still Missing]

Searching for clues

When Wildling examined the book, he found an irregularity in the library stamp, which suggested that the seal was fake. Counterfeiters sometimes forge seals from prestigious libraries to increase the value of rare books, Wilding said. But the "Sidereus Nuncius" copy already bore Galileo's signature, so why would a forger risk compromising that with a fake library seal?

"That made me wonder if the signature was applied at the same time and was also fake — and if the illustrations of the moon were fake, as well," Wilding said.

His suspicions were confirmed by Owen Gingerich, a professor emeritus of astronomy and history of science with the Department of the History of Science at Harvard University. Gingerich declared that the watercolors couldn't be Galileo's because they contained a significant "astronomical blunder," The New York Times reported in 2012. Book dealers also said the book's pages didn't feel or sound like 17th-century paper, Wilding added.

But the "eureka moment" for Wilding came when he found photos of pages from another copy of "Sidereus Nuncius" that De Caro had tried to sell through Sotheby's in 2005. Both the Sotheby's copy and the Martayan Lan copy had an identical mark on their pages. It didn't appear in other genuine copies, but Wilding tracked it to a blotch that showed up in a scan of a genuine edition, made in 1964.

Wilding was unable to inspect the Sotheby's copy, but he found that the blotch in the Martayan Lan book was indented, as though it had been pressed into the paper with a printing plate. He explained that De Caro had reverse-engineered a 3D plate by photographing that scan, and he mistakenly included the blotch from the scan into the plate.

This particular copy of "Sidereus Nuncius" was exposed as a fake, but De Caro has admitted that he created other counterfeit copies. Those forgeries may currently be circulating through unknown channels in the criminal underworld, Wilding added.

"He's admitted to making four other copies," Wilding said. "The mere fact that more than one forgery exists means that it wasn't just an isolated, elaborate hoax — it was part of a wider campaign to steal thousands of books, usually from state-run libraries," he said.

"Secrets of the Dead: Galileo's Moon" premieres July 2 at 8 p.m. on PBS (check local listings), pbs.org/secrets and the PBS Video app as part of PBS' "Summer of Space."

- 6 Archaeological Forgeries That Could Have Changed History

- 9 Famous Art Forgers

- Cracking Codices: 10 of the Most Mysterious Ancient Manuscripts

Originally published on Live Science.