Scientists reconstruct Aeolus satellite's fiery fall to Earth from space

The wind-measuring satellite reentered the atmosphere over Antarctica burning up far from population centers.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

On Friday, July 28, the wind-measuring spacecraft Aeolus made its fiery return to Earth, disintegrating high above the planet's surface in the first controlled reentry of its kind.

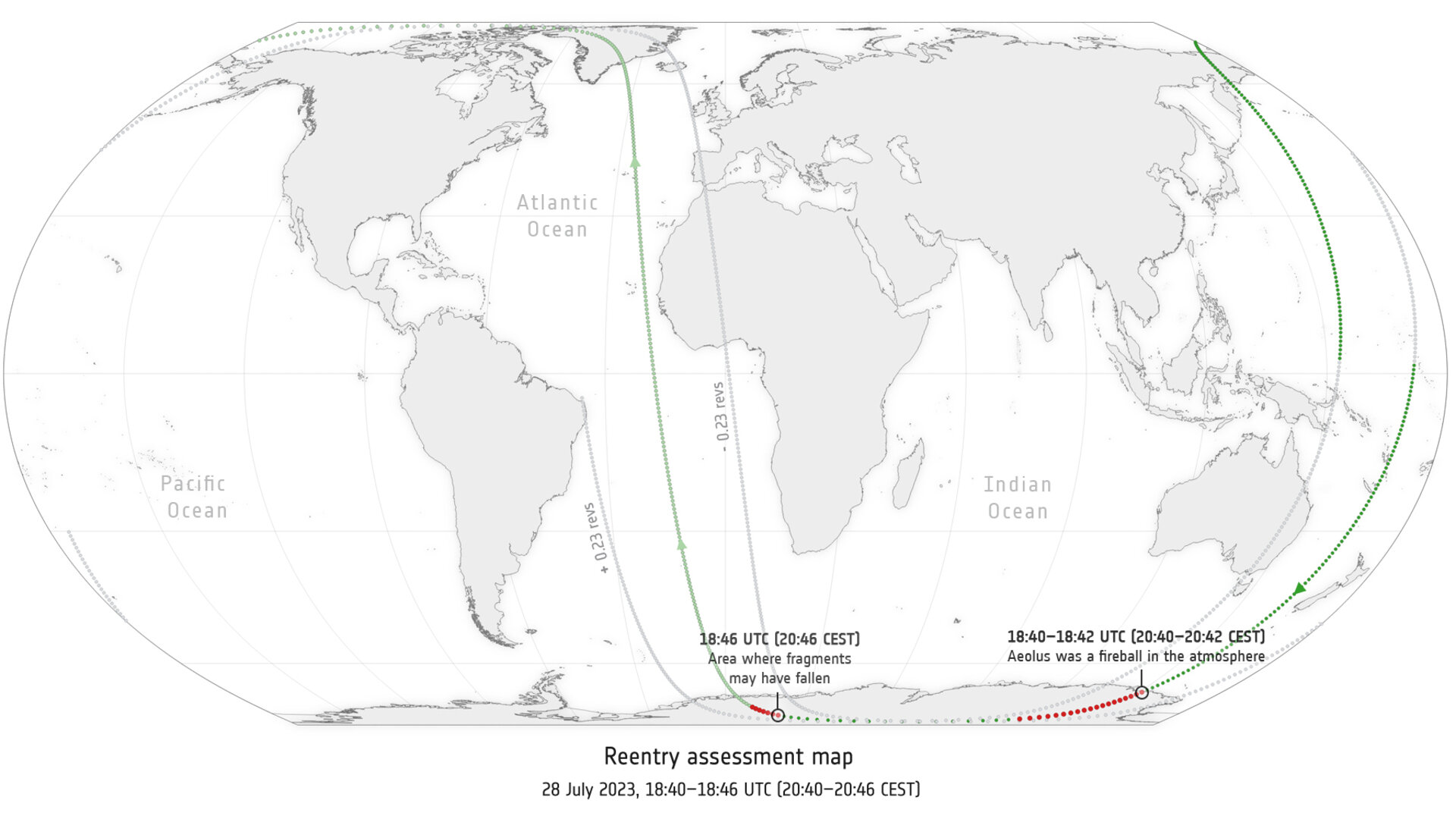

Now, about one week later, engineers at the European Space Agency (ESA) have calculated the descent path of Aeolus, the first satellite ever to measure the winds of Earth from space and named after the keeper of the winds in Greek mythology.

Guiding Aeolus back to Earth was a tricky operation, the goal of which was for Aeolus to hit Earth as far away from population centers as possible as up to one quarter of the satellite was expected to make it all the way down to the surface.

Aeolus was brought down using a series of maneuvres beginning on Monday, July 24, and though the mission, which used the spacecraft's remaining fuel was a success, no one was around to see Aelous go down in a blaze of glory as the satellite entered Earth's atmosphere at 14:40 EDT (1840 GMT) that day over Antarctica.

Related: ISS experiment to help develop air conditioning for future space habitats

ESA's Space Debris Office used data collected during the final orbit of Aeolus together with data from U.S. Space Command to build a map that shows the approximate location of the spacecraft's disintegration in Earth's atmosphere. This process was believed to have destroyed around 80% of the spacecraft, but the map was also able to determine where in the Atlantic Ocean the remaining 20% was dispersed.

The map revealed that upon reentry and for just two minutes, Aeolus became a fireball over Earth, a manmade shooting star streaking through the atmosphere over Antarctica.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

At six minutes after reentry, the team marked the location at which any surviving pieces would have fallen into the ocean. There are no plans to recover these fragments, which would have quickly sunk to the sea floor.

This final position marked on the map is remarkably close to the planned resting location of Aeolus, despite the spacecraft having never been designed for such a controlled descent or for flying at low altitudes.

The achievement of landing the craft minutes from its target is even more impressive, considering that Aeolus was traveling at around 17,000 miles per hour (27,360 kmh) , about 11 times faster than the top speed of a fighter jet.

Planning the fall of Aeolus

The ESA team that engineered the fall of Aeolus had several potential descent paths to choose from, but they eventually decided on one that would guide the satellite down a long path over the Atlantic Ocean. This was favorable as it saw Aeolus descend as far away from inhabited regions as possible during its final Earth orbit.

The guided reentry is estimated to have reduced the risk of surviving fragments landing near populated areas by a factor of 150. The risk of getting struck by man-made space debris is infinitesimally small. Although there have been no major incidents of injury or property damage as the result of such an incident so far, pieces of the first U.S. space station Skylab fell on a farm in Australia in 1979, and there have been multiple reports of Chinese rocket stages crashing on Asian villages. ESA therefore takes the issue of reentering spacecraft seriously.

The example set by Aeolus can now be applied to other satellites in orbit around Earth that are too large to burn up completely in Earth's atmosphere.

"Space is limited and shared, and therefore space sustainability must be a global effort," head of ESA's Space Safety Programme Holger Krag said in a statement. "To ensure spaceflight for the future, we need to significantly improve the way we design and operate missions today. With Aeolus, we decided to go well beyond what Aeolus was required to do."

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.