Earthquakes: What are they and how do they occur?

Earthquakes are one of Earth's biggest and deadliest natural disasters.

Spawning below Earth's surface and carrying immense energy, earthquakes can strike without warning. It therefore comes as no surprise that they are one of our planet's deadliest natural disasters.

Earthquakes occur when vast amounts of energy are released from Earth's crust in the form of seismic waves. The waves radiate outwards from the source of the stress, known as the hypocenter, and can cause untold damage to infrastructure when they reach the surface.

Approximately 20,000 earthquakes occur every year, which equates to around 55 every single day according to the United States Geological Survey (USGS). Fortunately for us, the majority of these go completely unnoticed and are too weak to cause any damage.

Related: Haiti's earthquake aftermath is visible from space

Daisy joined Space.com in February 2022, before then she worked as a staff writer for our sister publication All About Space magazine. Daisy has a Ph.D. in plant physiology and an MSci in environmental science. She has written numerous Earth-focused articles including a guide to Earth's magnetic field, everything you need to know about noctilucent clouds and a countdown of 15 places on Earth that look like they're from another planet.

Scientists anticipate approximately 16 major earthquakes (categorized as magnitude 7 and above) per year, after studying long-term records from about 1900. According to USGS, in the last 40 to 50 years we have exceeded this number approximately 12 times, and in 2010 alone we experienced 23 major earthquakes.

But that's about as far as our earthquake prediction capabilities go, as these seismic beasts are virtually impossible to predict and entirely unpreventable. Instead of investing time and energy into futile preventative measures. Humans have learned that preparedness and appropriate infrastructure are key. As the famous saying goes "earthquakes don't kill people, buildings do."

Many areas that are prone to earthquakes have adopted rigorous building codes to help ensure that new buildings or adjustments to old ones are done with earthquake resistance in mind. There are myriad examples of building improvements, from rubber shock absorbers in the foundations to help absorb tremors to special steel frames designed to sway without affecting the structural integrity of the building.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

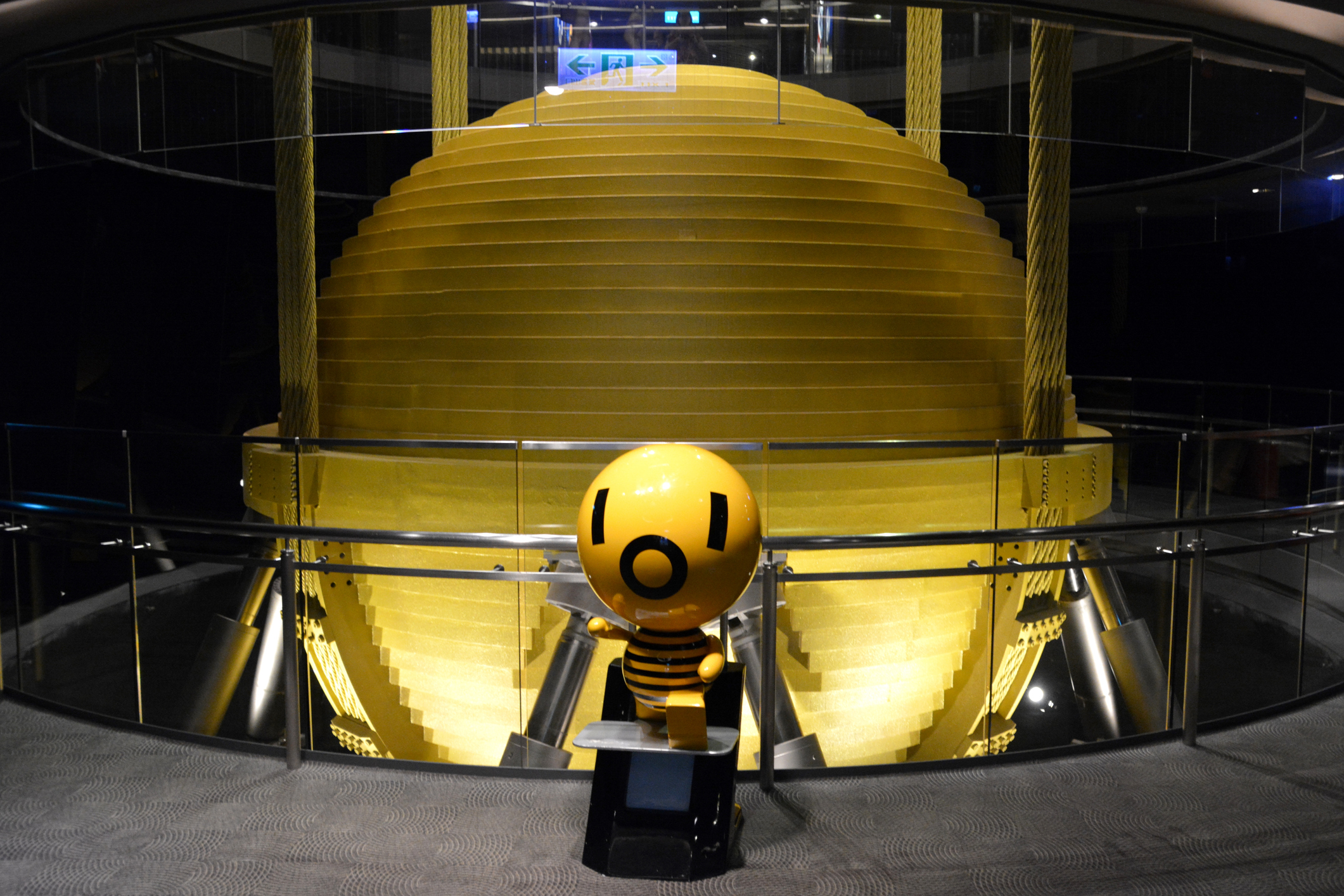

Remarkably, large skyscrapers can also be constructed to withstand considerable ground shaking. Some are built containing large stabilizing balls known as "dampers" which essentially act as giant pendulums, moving back and forth to counter any movement of the building itself. These dampers help stabilize the building during high winds, or seismic activity. You can see one of these dampers for yourself from the observation deck in the famous Taipei 101 building in Taiwan.

What causes earthquakes?

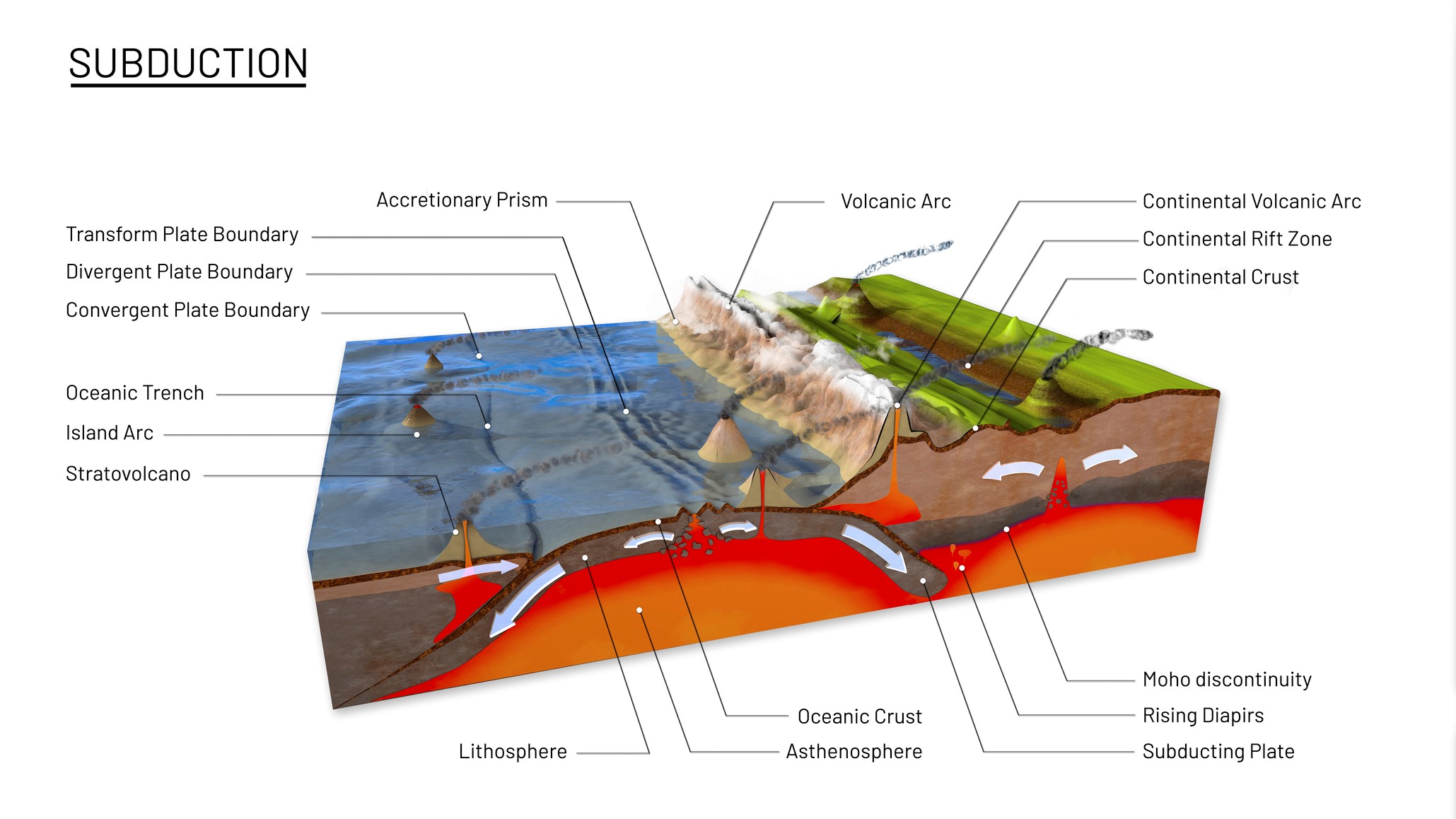

Earthquakes are triggered by a variety of processes including volcanic eruptions, landslides and even meteor strikes. But the most common cause of earthquakes lies deep below our feet in the form of plate tectonics.

Sandwiched between the atmosphere above and the asthenosphere below (the upper layer of the earth's mantle) lies the outermost layer of Earth — the lithosphere. This layer consists of numerous pieces, or plates, that jostle around on top of the asthenosphere like an energetic jigsaw puzzle. Temperatures in the asthenosphere range from 2,370 degrees Fahrenheit to 3,090 degrees Fahrenheit (1,300 degrees Celsius to 1,700 degrees Celsius) and the depth ranges from 62 miles to 155 miles (100 km to 250 km) below Earth's surface. The high temperatures result in the asthenosphere layer having enough elasticity to "flow" — despite being solid — according to the educational website Study.com. This ductile layer can flow slowly under heat convection and help move magma and rocks through Earth, contributing to the movement of tectonic plates.

When two plates attempt to move past each other, friction prevents them from gliding on by with relative ease, causing stress to build up at the point of contact. Though their movement is hindered, the plates never stop moving, so ultimately something has to give.

Eventually, the rock slips, releasing vast amounts of energy in waves that travel through Earth's interior to the surface and generate the shaking we perceive during an earthquake. The point on Earth's surface that lies directly above the focus — or hypocenter — of the earthquake is known as the epicenter.

Earthquakes can arise anywhere between Earth's surface and around 700 kilometers deep according to a statement from USGS. They're prevalent along the edges of plate boundaries and according to the British Geological Survey, over 80% occur around the edge of the Pacific Ocean, in an area known as the "Ring of Fire." Some earthquakes, however, can appear far from boundaries, right in the middle of the plate. These are known as intraplate quakes and although little is known about them, some scientists believe that they result from preexisting faults that formed within Earth's crust long ago.

How are earthquakes detected and measured?

The branch of science relating to the study of earthquakes and related events is known as seismology.

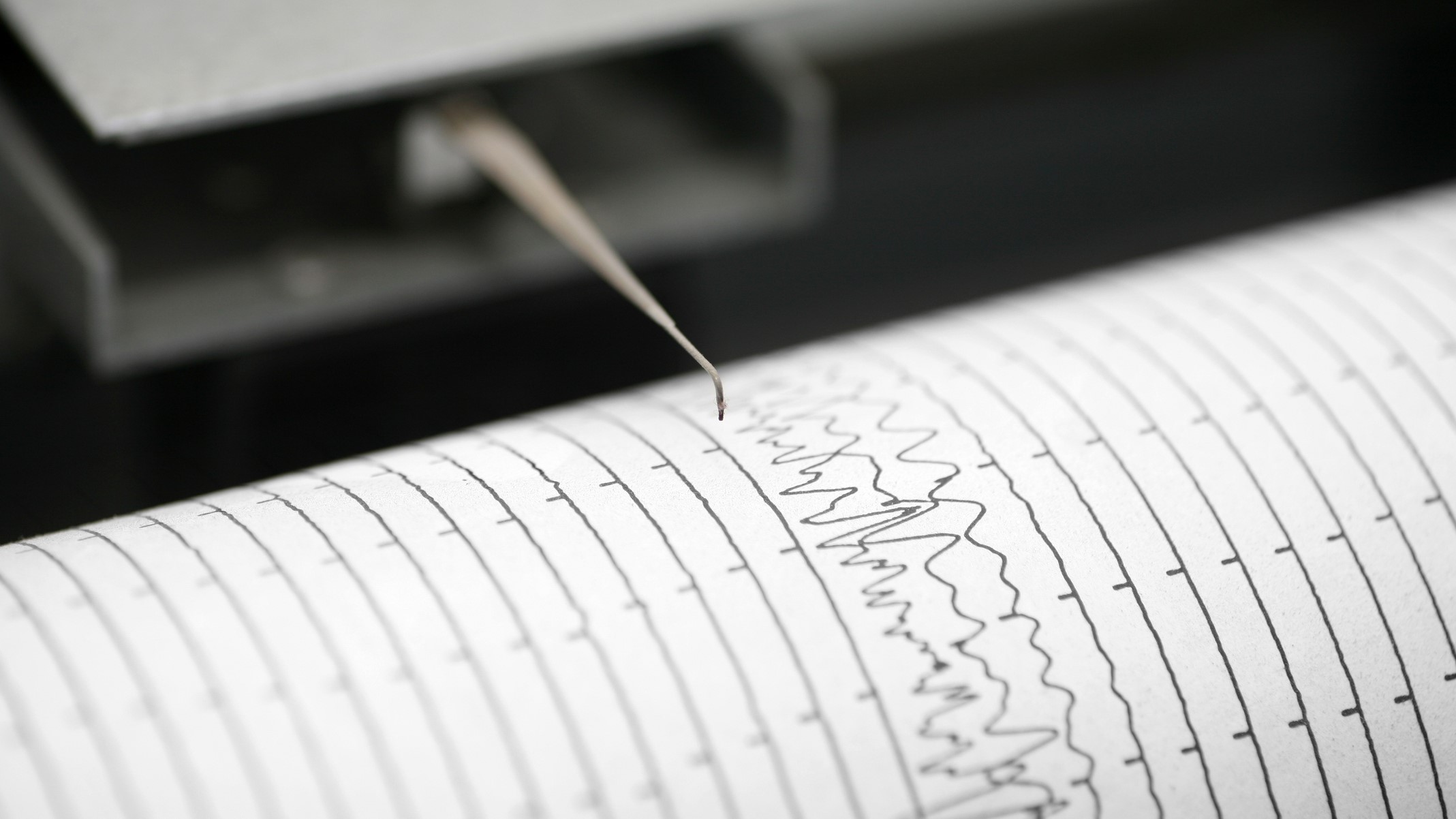

A seismograph or seismometer is an instrument used to detect and measure ground movements caused by seismic activity. A seismogram is the record of ground movements, according to the British Geological Survey. A simple seismometer consists of a pen attached to a suspended mass which — when the ground moves — will move due to its inertia and record the movements on a rotating drum of paper. More sophisticated seismometers record the motion of the ground in three dimensions: up and down, east to west and north to south.

Scientists use this data to calculate the size of the earthquake, known as magnitude.

The Richter scale is perhaps the most well-known way of measuring an earthquake's magnitude. Developed in 1935 by Charles F. Richter, this logarithmic scale was designed to compare the size of earthquakes in the California region.

The Richter scale goes from 1 to 10, whereby one increase in the scale accounts for a 10-fold increase in magnitude. The magnitude of the earthquake relates to the amplitude (distance from the center line to the top of the crest or bottom of a trough of a wave) of the waves recorded by the seismograph.

One problem with this technique is that earthquake wave amplitudes are not only affected by the earthquake itself, but also by the distance between the seismometer and the epicenter and even the type of rock the waves are traveling through. As such, various adjustments need to be made to seismometer data to account for the variations in conditions, so that the calculated magnitude is the same regardless of where it was measured.

As more and more seismometers were installed around the world, it became incredibly difficult to adjust the data to make it "fit" with the Richter scale as it became apparent that the scale only worked for certain frequency and distance ranges, according to the USGS.

Scientists, therefore, came up with a new scale that can be used all over the world called moment magnitude. The moment refers to the amount of energy released at the time of slip on the fault multiplied by the area of the fault surface affected. It can be estimated using seismometers and is related to the total energy released in the earthquake. Moment magnitude is the most reliable estimate of earthquake size.

The effect of an earthquake on Earth's surface — the intensity — is evaluated with the Modified Mercalli (MM) Intensity Scale. The scale is rather ambiguous, as it is not based on numerical values but instead assigns a ranking based on observable effects. This could be misleading as two earthquakes of the same magnitude striking two areas with different levels of earthquake preparedness or of different geological compositions will result in the assignment of very different intensity rankings.

Biggest earthquake

The biggest earthquake ever recorded was in 1960 when a magnitude 9.5 quake struck Chile. Named the Valdivia earthquake after the city most affected by the quake, it left 2 million people without homes, injured at least 3,000 and killed around 1,655 according to National Geographic.

Benefits of Earthquakes

It might be surprising to hear that earthquakes can be beneficial, but they can actually tell us a lot about Earth's interior, including where different geological layers are located.

When seismometers around the world detect seismic waves, they record their velocities, which tell scientists a great deal about the composition, temperature and pressure of the material through which the waves have traveled.

The location and magnitude of an earthquake can also provide a window into the Earth's tectonic processes at work. Increased tectonic knowledge helps scientists improve their calculations of the probability of seismic events along particular faults, according to the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Do earthquakes happen on other planets?

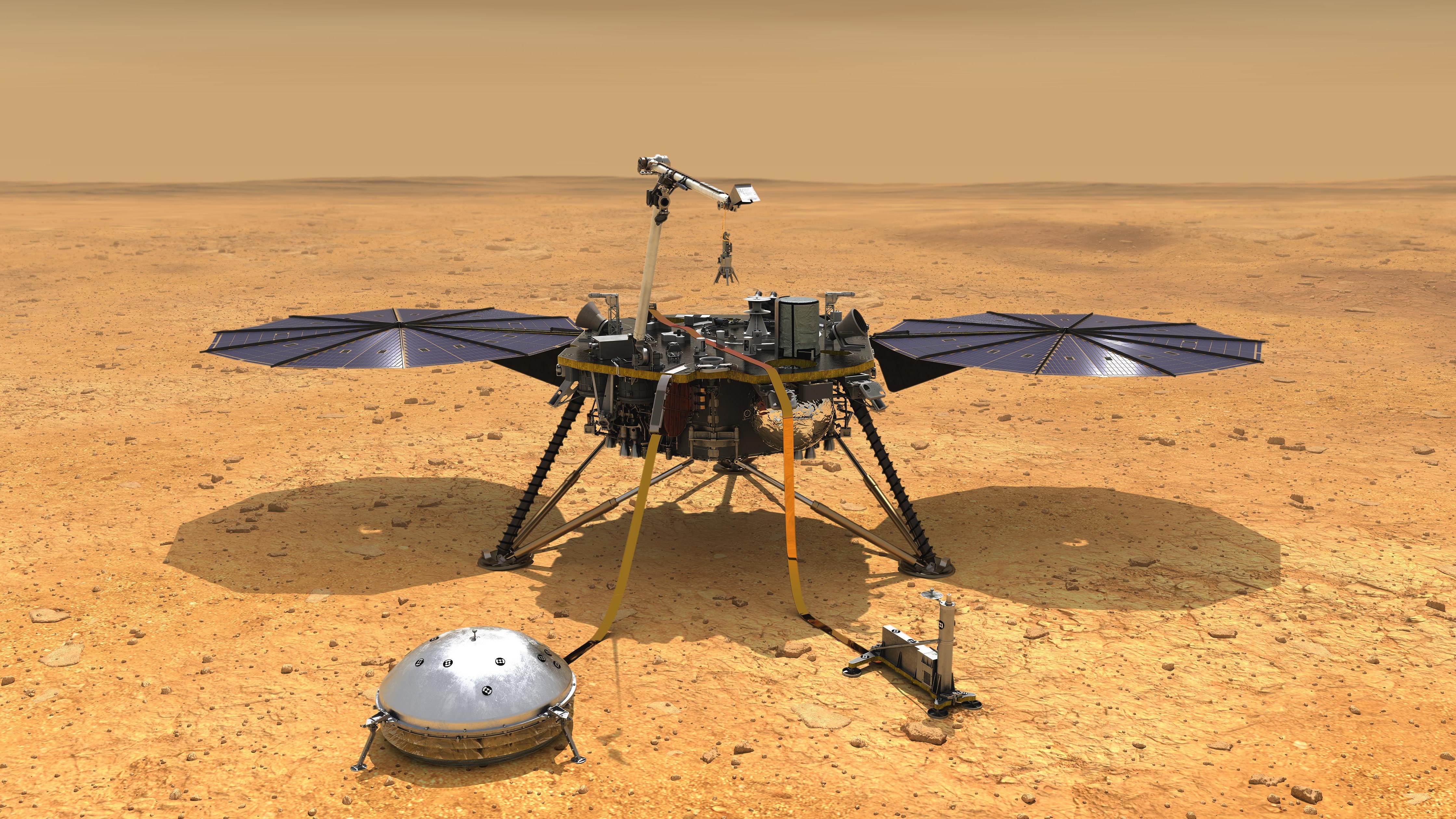

At present, we do not know of any other planet that possesses a lithosphere divided into true plates that undergo tectonic processes, according to the Lunar and Planetary Institute. That being said, that isn't to say that quakes don't exist elsewhere in the solar system, for there is more than one way to trigger a seismic event.

Moonquakes and marsquakes have both been detected, allowing researchers to probe further into the interiors of these distant worlds.

According to Horizon magazine, moonquakes are caused by:

- Meteoroids hitting the lunar surface

- Earth's gravitational pull stretching and squeezing the moon's interior.

- Buckles and breaks from the lunar crust as a result of the moon cooling down.

- Heating from the sun triggering thermal quakes

The first seismometer on the moon was actually placed there during Apollo 11 and was even put to the test by Buzz Aldrin stamping his foot nearby (the instrument recorded it), according to the EU Research and Innovation Magazine, Horizon. Several other seismometers were deployed on subsequent Apollo missions and collected valuable seismic data.

The seismometers were operational until 1977. Data collected from the instruments is still being analyzed by scientists as there are currently no active lunar seismometers.

Scientists are hopeful that future missions to the moon under the Artemis program will see more sophisticated seismometers deployed on the lunar surface so we can peer even further into its interior.

Turning our attention to the Red Planet, we had to wait a little longer to witness seismic activity on Mars. The first marsquake was detected by NASA's InSight Mars Lander on Apr. 6, 2019, with its Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument. Since then, over 1,300 marsquakes have been detected by the lander, including a magnitude 5 on May. 4, 2022 — the strongest tremor ever detected on a planet besides Earth.

Additional resources

To learn more about what to do in the event of an earthquake the U.S. government has some dedicated resources designed to help you stay safe. If you want to know more about the latest seismic events check out this interactive map from USGS detailing the latest earthquakes around the world. Read about how NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory is using satellite data to help map earthquake damage so we can learn more about these seismic events.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and Facebook.

Bibliography

Determining the depth of an earthquake. Determining the Depth of an Earthquake | U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.usgs.gov/programs/earthquake-hazards/determining-depth-earthquake

Earthquake facts & earthquake fantasy. Earthquake Facts & Earthquake Fantasy | U.S. Geological Survey Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.usgs.gov/programs/earthquake-hazards/earthquake-facts-earthquake-fantasy

Earthquake glossary. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://earthquake.usgs.gov/learn/glossary/?term=richter+scale

Earthquakes. National Geographic Society. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/earthquakes

Earthquakes. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.whoi.edu/know-your-ocean/ocean-topics/ocean-human-lives/natural-disasters/earthquakes/

How are earthquakes detected, located and measured? British Geological Survey. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.bgs.ac.uk/discovering-geology/earth-hazards/earthquakes/how-are-earthquakes-detected

Keesey, L. (April 29, 2020). NASA scientists to make seismometer system to measure Moonquakes. NASA. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2020/nasa-scientists-tapped-to-mature-more-rugged-seismometer-system-to-measure-moonquakes

May 22, 1960 CE: Valdivia earthquake strikes Chile. National Geographic Society. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/valdivia-earthquake-strikes-chile

The modified Mercalli intensity scale. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.usgs.gov/programs/earthquake-hazards/modified-mercalli-intensity-scale

Moment magnitude, richter scale - what are the different magnitude scales, and why are there so many? U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/moment-magnitude-richter-scale-what-are-different-magnitude-scales-and-why-are-there-so-many

O'Callaghan, J. (August 10, 2020). Moonquakes and Marsquakes: How we peer inside other worlds. Horizon Magazine. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://ec.europa.eu/research-and-innovation/en/horizon-magazine/moonquakes-and-marsquakes-how-we-peer-inside-other-worlds

Shaping the planets: Tectonism. Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI). Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.lpi.usra.edu/education/explore/shaping_the_planets/tectonism/

What is the asthenosphere? Study.com. Retrieved October 18, 2022 from https://study.com/learn/lesson/asthenosphere-temperature-facts-density.html

What keeps the continents floating on a sea of molten rock? Surprising questions with surprising answers. West Texas A&M University. Retrieved October 18, 2022, from https://www.wtamu.edu/~cbaird/sq/2013/07/18/what-keeps-the-continents-floating-on-a-sea-of-molten-rock

Where do earthquakes occur? British Geological Survey. Retrieved October 13, 2022, from https://www.bgs.ac.uk/discovering-geology/earth-hazards/earthquakes/where-do-earthquakes-occur/

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!