The closest black hole to Earth doesn't actually exist

It's a classic case of mistaken identity — and stellar vampirism.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

In 2020, a team of astronomers with the European Southern Observatory (ESO) discovered the closest black hole to Earth in the HR 6819 system, just 1,000 light-years away, only to have other scientists dispute the findings.

As it turns out, those critics seem to have been correct. In new research, an international team of scientists led by researcher Abigail Frost of KU Leuven in Belgium has disproved the existence of a black hole in HR 6819.

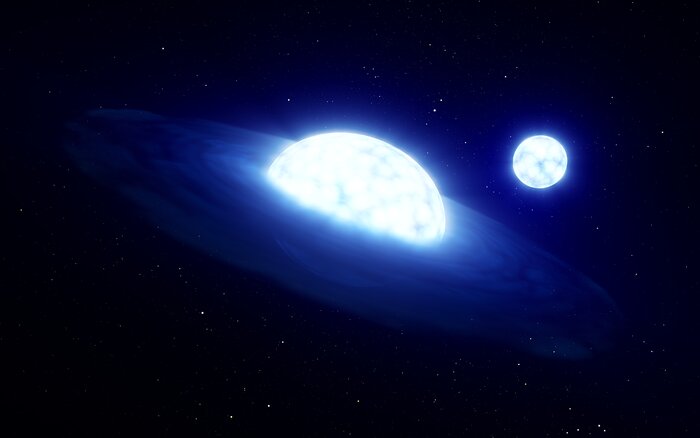

The original research, published in a 2020 paper authored by ESO astronomer Thomas Rivinius, determined that HR 6819 was a triple system, with one star closely orbiting a black hole and another star in a wide orbit. But a 2020 study by Julia Bodensteiner, then a Ph.D. candidate at KU Leuven and now a fellow with ESO, posited that the system could also contain just two stars if one was stripping away and absorbing much of the mass of the other, a phenomenon that's sometimes referred to as "stellar vampirism."

Related: 8 ways we know that black holes really do exist

The trio of researchers decided to team up to investigate HR 6819 more closely and determine which explanation was more likely.

"The scenarios we were looking for were rather clear, very different and easily distinguishable with the right instrument," Rivinius said in a statement. "We agreed that there were two sources of light in the system, so the question was whether they orbit each other closely, as in the stripped-star scenario, or are far apart from each other, as in the black hole scenario."

While Rivinius' original research was based on observations gathered by a relatively small telescope, the new team turned to ESO's Very Large Telescope (VLT) and Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI) for their research — two powerful instruments based in Chile that could produce more detailed images of HR 6819 than the tools used in Rivinius' first study.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

With the more powerful observations, the situation in HR 6819 was clear — there are only two stars in a tight orbit, and no black hole to speak of. But the absence of a black hole is nothing to mourn.

"Our best interpretation so far is that we caught this binary system in a moment shortly after one of the stars had sucked the atmosphere off its companion star," Bodensteiner said in the statement. That interpretation confirms the stellar vampirism theory.

"Catching such a post-interaction phase is extremely difficult as it is so short," Frost said in the statement. "This makes our findings for HR 6819 very exciting, as it presents a perfect candidate to study how this vampirism affects the evolution of massive stars, and in turn the formation of their associated phenomena, including gravitational waves and violent supernova explosions."

The results are described in a paper published Wednesday (March 2) in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Follow Stefanie Waldek on Twitter @StefanieWaldek. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Space.com contributing writer Stefanie Waldek is a self-taught space nerd and aviation geek who is passionate about all things spaceflight and astronomy. With a background in travel and design journalism, as well as a Bachelor of Arts degree from New York University, she specializes in the budding space tourism industry and Earth-based astrotourism. In her free time, you can find her watching rocket launches or looking up at the stars, wondering what is out there. Learn more about her work at www.stefaniewaldek.com.