Book excerpt: 'A City on Mars'

"When you just talk about technical things like the size of rockets, or whether Mars has water and carbon, the picture can look pretty solid. When you get into the more squishy details of human existence, things start to look, well, squishy."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

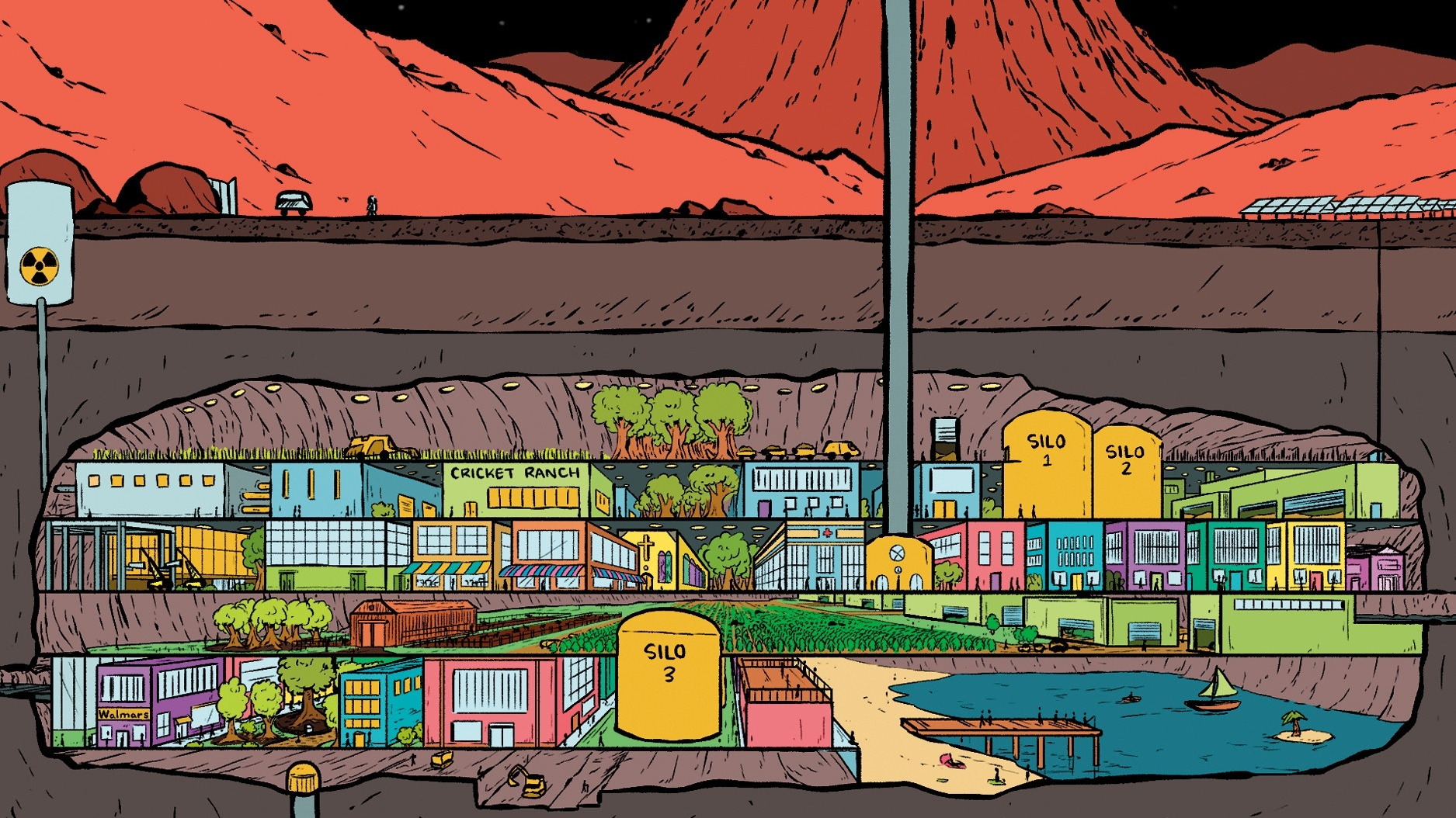

Establishing long-term presence beyond Earth is now firmly viewed as the collective goal for humanity, some even believe it to be the only way to ensure our survival. The moon and Mars are thought to be the most exciting destinations thought to be within reach. The cost of access to space has significantly lowered since the 1950s, bringing the tantalizing dream of human space settlement closer to reality now than it was ever before. But there are many first-order questions about becoming multiplanetary we haven’t explored yet, like having space kids, building space farms and creating space nations in a peaceful way, according to authors Kelly and Zach Weinersmith. In their riveting new book, "A City on Mars: Can we settle space, should we settle space, and have we really thought this through?" (Penguin Press, 2023), the Weinersmiths analyze many questions and challenges about human space settlement by blending science, psychology, law and perhaps what makes the book a surprisingly easy read — humor.

(Read an interview with Kelly Weinersmith here.)

Excerpt from Chapter 1: Introduction

We read about caves on the Moon, uncomfortably detailed orbital mating concepts, space madness, Moon law, plans for Martian company towns, hopes for new ways of life in distant worlds. We read dozens of old space books going back to the 1920s, many of them predicting imminent space settlements. We talked to experts in the economic and political fields who had little interest in space, but also to space advocates and space entrepreneurs. Friends, we are practically bursting with weird space knowledge. Did you know the Colombian constitution asserts a claim to a specific region of space? Did you know the first woman to step foot in a space station was "gifted" an apron and asked if she'd handle cooking and cleaning for the rest of her mission? Did you know an early space life-support concept involved a substance that could double as shelving and as breakfast? Did you know former US Republican Party presidential nominee Barry Goldwater once advocated sending bull semen to orbit to separate sperm for sex-selection purposes?

While we fell in love with space settlement as a field of study, we became more concerned about all the proposals for doing it in the coming decades. It turns out when you just talk about technical things like the size of rockets, or whether Mars has water and carbon, the picture can look pretty solid. When you get into the more squishy details of human existence, things start to look, well, squishy.

Especially squishy, for example, are space babies. Can we make them? Proposals for settlements often just assume you can safely have natural population growth. We don't know if this is true, and there are good reasons to suppose it isn't. A start-up called SpaceLife Origin announced in 2018 their goal of the first human birth in space by 2024. In 2019, their CEO left, citing "serious ethical, safety, and medical concerns." That's exactly right. Out of all the NASA astronauts, only five have spent nine consecutive months in space, only two of those five have been women, and none of them had to do it while being a fetus. As for the person around the fetus, they might have concerns too. Moms on Earth worry about things like eating sushi or having a beer. Try 1 percent bone loss per month while doing several hours of resistance training every day in a high-radiation, high-carbon-dioxide atmosphere without Earth-normal gravity. It's certainly possible everything will be fine, but we wouldn't want to bet on it. Given that population growth requires babies not just to be born, but to grow up to have their own babies, getting appropriate safety protocols would take decades, even if we unethically began doing experiments on humans starting tomorrow. But we aren't. The current state of the art is short, unsystematic experiments in orbit, like the one where geckos were sent up for some highly documented together time, before the experiment failed and everyone froze to death. C'est la vie dans l'espace.

Elon Musk says we'll have boots on Mars in 2029 and a million-person city is possible by twenty or thirty years later. We'll assume he's got space babies worked out for now so we can deal with a bigger problem: space sucks. Our impression talking to nongeeks is that while they realize space sucks, they have underestimated the scale of suckitude. We said above that you'd be crazy to leave Earth for Mars. This is true, but we should add that Mars is easily the most inviting place for space settlement. The runner-up is the Moon, which among its many shortcomings is very poor in carbon, the basic building block of life.

Excerpted from the book “A City on Mars: Can we settle space, should we settle space, and have we really thought this through?” Copyright © 2023 by Kelly and Zach Weinersmith. Reprinted with permission of Penguin Random House. All rights reserved.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You can buy "A City on Mars" on Amazon or Bookshop.org.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.