The hunt for asteroid impacts on the moon heats up with new observatory

Sometimes a flash in the night is actually an asteroid slamming into the moon.

Because such impacts offer valuable information about Earth's own barrage of space rocks, scientists have established programs that look for the brief bright flashes on the moon that represent lunar impacts. A new such telescope recently began operations, confirming observations of another telescope's 100th impact flash detection.

Having multiple eyes on the moon is valuable for scientists because other phenomena, like satellites passing overhead, can produce similar flashes in the data. But two observatories at different locations won't simultaneously see the same satellite: if both catch the same lunar flash at the same time, it's definitely real data.

Related: Watch a meteor smack the blood moon in this lunar eclipse video!

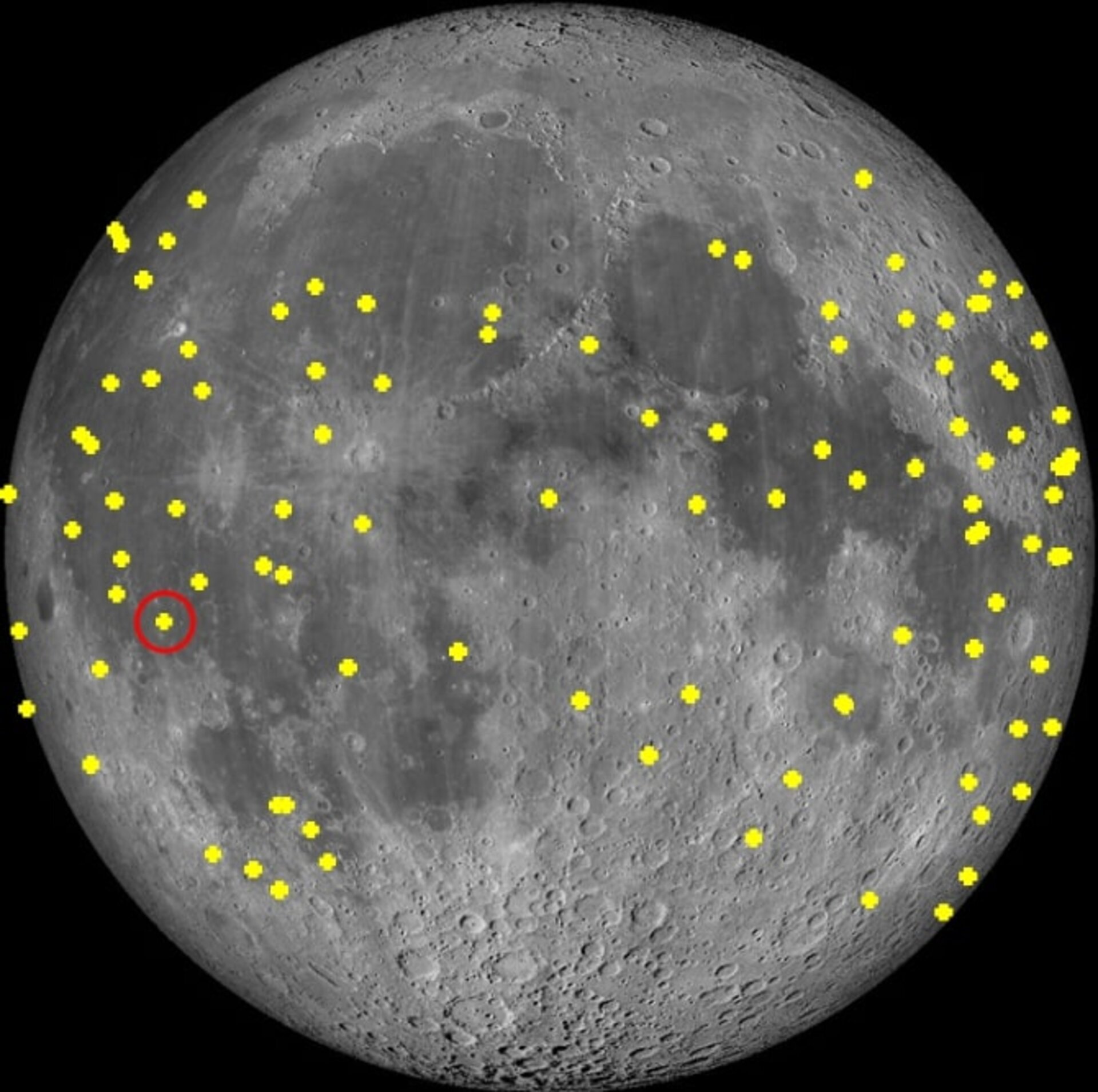

The European Space Agency's Near-Earth Object Lunar Impacts and Optical Transients (NELIOTA) project, based at Kryoneri Observatory in Greece, does just this type of work. So far, the project has spent nearly 150 hours staring at the moon and observed 102 flashes. The instrument can also provide data that lets scientists estimate the temperature of the impact.

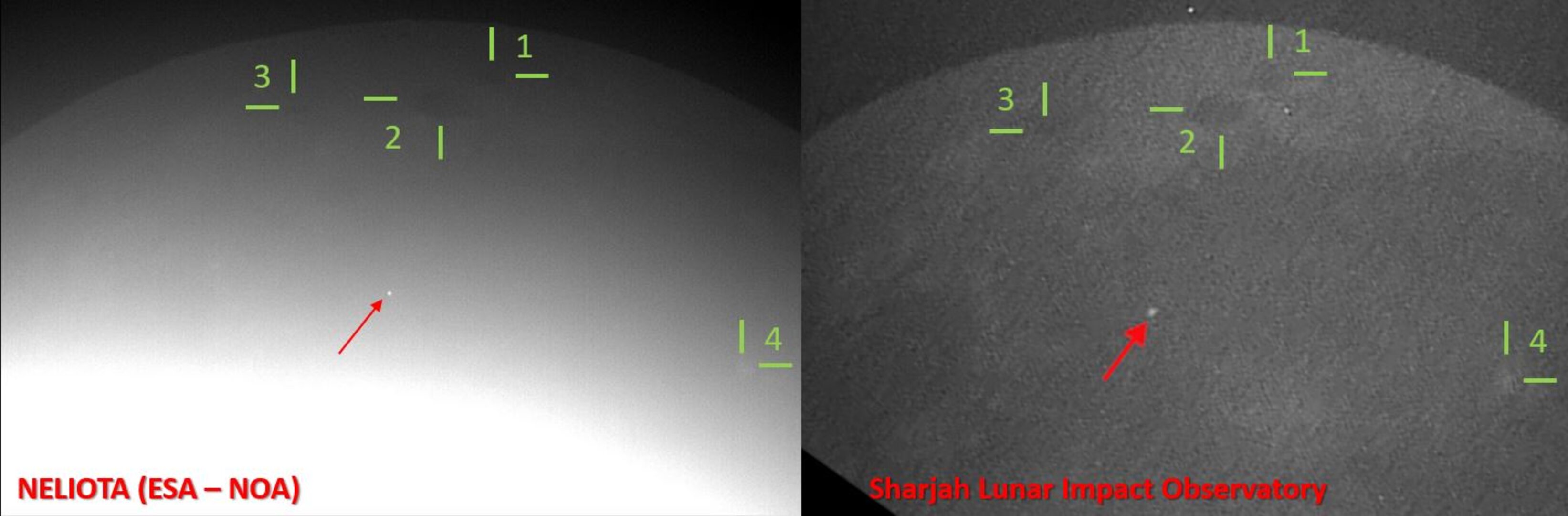

The milestone 100th observation came on March 1. And as scientists looked back over NELIOTA's data, they realized that a newcomer to the lunar impact patrol, the Sharjah Lunar Impact Observatory in the United Arab Emirates, had spotted the same flash. Scientists were able to compare images taken by the two observatories and line up lunar features, in addition to checking the timestamps of the flashes.

The double observation marks an important milestone for lunar impact surveillance efforts. "Cross detections like this are very useful as they rule out the possibility of a slow, bright satellite being misidentified as an impact flash," Detlef Koschny, co-manager of the Planetary Defense Office of the European Space Agency, said in a statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"While NELIOTA has other, less-direct means of excluding such events, we're excited to have more eyes on the moon, helping us to understand the rocky road our planet travels on," Koschny said. The Earth and moon are close enough — on the scale of the solar system — that both bodies should be hit by more or less the same hail of space rocks.

The flashes these observatories track come from just the sort of space rocks that regularly hit Earth without scientists being able to spot them: rocks that weigh less than 3.5 ounces (100 grams) and are less than 2 inches (5 centimeters) across, according to the statement. Rocks that small don't make it very far into Earth's thick atmosphere before burning away.

But the moon has no such atmosphere, so the same size rock can hit the surface — pretty flashy.

- It's time to get serious about asteroid threats, NASA chief says

- What if an asteroid was going to hit Earth? NASA will make believe this week

- NASA wants a new space telescope to protect us all from dangerous asteroids

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.