New Planet-Hunting Method Could Find Earth-Like Alien Worlds

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Anew planet-hunting technique that was used to detect an exotic alien world maybe sensitive enough to help astronomers search for Earth-sized planets thatorbit other stars, according to a new study.

Thenew approach, called Transit Timing Variation, was developed by a team ofEuropean astronomers led by Gracjan Maciejewski of Jena University in Germany.

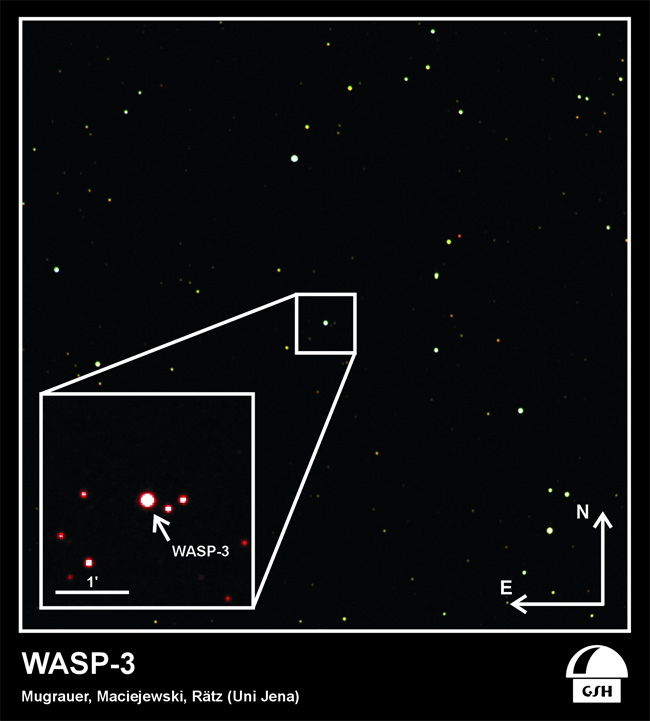

Thetechnique was used to pinpoint a planet that is 15 times the mass of Earth,located in the star system WASP-3, which is 700 light-years away from the sunin the constellation Lyra.

Themethod's high degree of sensitivity, however, could also make it a valuabletool for locating small planets with similar masses to Earth, the researchers said.

Theresults of the study have been accepted for publication in an upcoming issue ofthe journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Whatis Transit Timing Variation?

TheTransit Timing Variation (TTV) technique was suggested as a viable approach fordiscovering alien planets? or exoplanets ? a few years ago. It built on the existing transiting method,which has been employed for years to detect a number of exoplanets, and iswidely used by the Kepler and CoRoT space missions that scour the cosmos for Earth-like planets.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Transitsoccur when a planet passes in front of its parent star, temporarily blocking someof the star's light as seen from Earth. During these transits, astronomers canmeasure a drop in the host star's light, telling them that a planet has movedin front.

Thenew method allows astronomers to further identify smaller planets whose owntransits might not be enough to significantly dent their star's light output.However, if smaller planets exist in addition to a large planet, the lessersiblings will exert a gravitational tug on the larger planet that changes itsorbit, causing deviations in the regular cycle of transits.

TheTTV technique compares these deviations with predictions that are made fromextensive computer-based calculations. The estimates allow astronomers to inferthe preliminary makeup of the planetary system being studied ? including thepresence of possible Earth-like planets.

Combingthe WASP-3 system

Fortheir study, Maciejewski and his team of researchers used the 35-inch (90-centimeter)diameter telescopes at the University Observatory Jena and the 24-inch (60-centimeter)diameter telescope at the Rohzen National Astronomical Observatory in Bulgariato study the transits of WASP-3b, a large planet that has a mass 630 times thatof Earth.

Theirobservations led to an unexpected finding.

"Wedetected periodic variations in the transit timing of WASP-3b,"Maciejewski said in a statement. "These variations can be explained by anadditional planet in the system, with a mass of 15 Earth-mass (i.e. one Uranusmass) and a period of 3.75 days."

Thisnewly discovered planet was named WASP-3c, and is among the smallest exoplanetsfound to date. It is also one of the least massive planets known to orbit astar that is more massive than our sun.

UsingTTV for future searches

Thisfinding marks the first time that a new extrasolar planet has been discovered using the TTV method.

Thedetection of the smaller 15 Earth-mass planet makes the WASP-3 system veryintriguing, the researchers said.

Thenew planet's orbit is twice as long as the orbit of the more massive planet.Such a configuration is likely a result of the early evolution of the planetarysystem.

TheTTV method's ability to detect small perturbing planets could help astronomerslocate more of these Earth-like exoplanets in the future, the researchers said.

Forinstance, an Earth-mass planet will pull on a typical gas giant planet orbitingclose to its star, and cause deviations in the timing of the larger objects'transits of up to one minute. This effect is significant enough to be detectedwith relatively small 1-meter diameter telescopes. Any potential discoveriescan then be followed up with larger ground-based instruments.

- Gallery - Strangest Alien Planets

- Top 10 Extreme Planet Facts

- First Direct Photo of Alien Planet Finally Confirmed

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.