Giant Meteor Caused Jupiter Fireball, Scientists Say

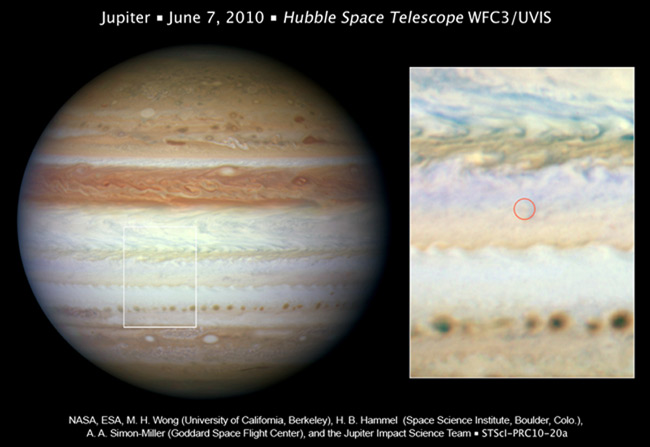

The mystery fireball that smacked into Jupiter on June 3 hasbeen identified as a giant meteor that plunged into the planet's atmosphere and burnedup high above its cloud tops, according to new observations from the HubbleSpace Telescope.

The cosmicintruder did not dive deep enough into Jupiter's atmosphere to explode,which explains the lack of any telltale cloud of debris, as was seen inprevious Jupiter collisions, said Hubble astronomers, who described the meteor's size as "giant" in a Wednesday announcement.

"We suspected for this 2010 impact there might be nobig explosion driving a giant plume, and hence no resulting debris field to beimaged," said Heidi Hammel, a veteran Jupiter observer at the SpaceScience Institute in Boulder, Colo., in a statement. "There was just themeteor, and Hubble confirmed this."

The meteor was huge, but not as large as the object thatstruck Jupiter in July 2009, or the shattered comet? fragments that hit the gasgiant planet in 1994, researchers said. [Gallery:Jupiter's 2009 crash.]

The new Hubble observations also allowed scientists to get aclose-up look at changes in Jupiter's atmosphere, following the disappearanceof the dark SouthernEquatorial Belt (SEB) several months ago.

In the latest Hubble view, a slightly higher altitude layerof white ammonia ice crystal clouds appears to obscure the deeper, darker beltclouds.

"Weather forecast for Jupiter's South Equatorial Belt:cloudy with a chance of ammonia," Hammel said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers predict that these ammonia clouds willlikely clear out in a few months, as it has typically done in the past.

Jupiter gets whacked (again)

The tale of Jupiter's latest cosmic hit is one that kept scientistsguessing until now.

It was Australian amateur astronomer Anthony Wesley whofirst saw the flash at 4:31 p.m. (EDT) on June 3, while watching a live videofeed of Jupiter from his telescope. Meanwhile, in the Philippines, amateurastronomer Chris Go confirmed the discovery from his own simultaneous videorecording of the transitory event.

Astronomers around the world determined that an object musthave whacked the gas giant in order to unleash a flash of energy that wasbright enough to be seen 400 million miles (643.7 million km) away. But, withno visiblescar or debris cloud from the impact, there was no telling how deep theobject penetrated into the atmosphere.

The Hubble Space Telescope's sharp vision and ultravioletsensitivity was called into action to seek out any traces of the aftermath ofthe cosmic collision.

Images taken on June 7 ? a little over three days after theflash was discovered ? showed no sign of debris above Jupiter's cloud tops. Thatsuggests the object did not descend beneath the clouds and explode as afireball, astronomers said.

"If it did, dark sooty blast debris would have beenejected and would have rained down onto the cloud tops, and the impact sitewould have appeared dark in the ultraviolet and visible images due to debrisfrom an explosion," Hammel explained. "We see no feature that hasthose distinguishing characteristics in the known vicinity of the impact,suggesting there was no major explosion and fireball."

Jupiter impacts of times past

Dark smudges marred Jupiter's atmosphere after pieces of thecometShoemaker-Levy 9 slammed into the planet in 1994. A similar phenomenonoccurred more recently in July 2009, when a suspected asteroid estimated to beabout 1,600 feet (500 meters) wide collided with Jupiter.

This latest cosmic interloper is estimated to be only afraction of the size of these previous impactors.

The two-second-long flash of light in the videos was createdby the same physics that causes a meteor or "shooting star" on Earth.A shock wave is generated by ram pressure as the meteor speeds into theplanet's atmosphere, heating the impacting body to a very high temperature.

As the hot object streaks through the atmosphere, it leavesbehind a glowing trail of superheated atmospheric gases and vaporized meteormaterial that then rapidly cools and fades in the span of only a few seconds.

Though astronomers are still uncertain about the rate ofsuch large meteoroid impacts on the planets in our solar system, it isestimated that the smallest detectable events may happen as frequently as everyfew weeks.

"It's difficult to even know what the current impactrates are throughout the solar system," said Amy Simon-Miller of NASA'sGoddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., the principal investigator onthe Jupiter observation. "That's partly why we are so excited by thelatest impact. It illustrates a new capability that can be exploited withincreased monitoring of Jupiter and the other planets."

Meteors on other planets

Even when impacts are detected, they can sometimes bemisread.

"The meteor flashes are so brief they are easilymissed, even in video recordings, or perhaps misidentified as detector noise orcosmic ray hits on imaging devices," said research team member Mike Wongof the University of California at Berkeley.

As for Jupiter's missing cloud belt, Hubble scientists saidthe space telescope's new photos showed all the warning signs of an impendingdisappearance of the planet's Southern Equatorial Belt.

The clearing of the ammonia cloud layer should begin with anumber of dark spots like those seen by Hubble along the boundary of the southtropical zone.

"The Hubble images tell us these spots are holesresulting from localized downdrafts taking place," Simon-Miller said."We often see these types of holes when a change is about to occur."

"The SEB last faded in the early 1970s,"Simon-Miller added. "We haven't been able to study this at this level ofdetail before. The changes of the last few years are adding to an extraordinarydatabase on dramatic cloud changes on Jupiter."

- Gallery - Photos of Latest Jupiter Collision

- Video - The Jupiter Crash of Shoemaker-Levy 9

- Astronomers Perplexed by Jupiter Collisions

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.