Whistling Helium: Supercold Sound May Lead to Better GPS in Submarines

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Researchers working with a type of super-cooled helium have made the frigid stuff whistle, an attribute they say might make it the crux of better global positioning systems (GPS) in submarines and airplanes among other things.

The trick, it turns out, resides in cooling a specific flavor of helium - called helium-4 - down to just two degrees above absolute zero (2 degrees Kelvin or -271 degrees Celsius), where it becomes a frictionless superfluid.

It is that superfluid, the scientists said, that whistled unexpectedly when squashed through tiny holes and could be the foundation of new superfluid gyroscopes for submersible GPS navigation and seismic measurements on Earth and in space. [Click here to hear the helium-4 whistle.]

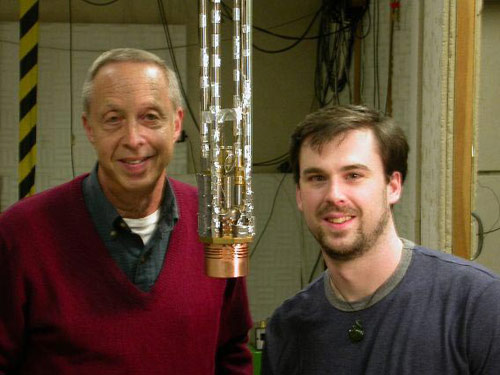

"The fact that they do whistle coherently means that we could make a sensitive gyroscope," explained UC Berkeley physicist Richard Packard, who led the study, in a telephone interview

The research, which was funded by NASA and the National Science Foundation, appeared in the Jan. 27 issue of the journal Nature.

Submarine GPS and earthquake studies

With almost no moving parts, superfluid gyroscopes promise much more sensitivity to rotational motion than their mechanical counterparts, a useful trait considering that changes in the Earth's rotation must constantly be added to the GPS system.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Presently, the Earth's rotation is measured by radio telescopes around the world," Packard said. "But if a superfluid gyroscope were used, it could make the measurement with a faster turnaround."

In Packard's study, cooled liquid helium-4 was forced through a network of holes, each of which was 1,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair. But instead of an ever-increasing acceleration, the frictionless fluid reached a critical velocity where microscopic whirlpools formed around each hole and abruptly slowed the helium flow. The changes from fast to slow helium flow caused vibrations detected by a microphone and heard as a quantum whistle by graduate student Emile Hoskinson.

Since the whistle changes volume relative to a vehicle's motions, submarines, as well as ships and airplanes in regions where GPS may not be available, could rely on whistling superfluid gyroscopes in their navigational systems.

Inertial navigation systems in ships rely on a combination of three gyroscopes and three accelerometers to determine position, Packard said.

A rotation-sensitive superfluid gyroscope could also help seismologists measure how the Earth's surface twists during an earthquake and build a better picture of the planet's structure, he added.

A warmer alternative

Despite helium-4's frigid temperature, researchers said it is actually the warmth of the gas that makes it a prime candidate for superfluid gyroscopes.

To stay a superfluid, liquid helium-4 must be kept at about 2 degrees Kelvin, a temperature range offered in commercially-available instruments called cryostats. Previous whistling helium gyroscopes experiments- including some by Packard - have centered on helium-3, which must be kept much colder (about one-thousandth of a degree above absolute zero) in complicated refrigerators.

"That kind of refrigerator has the complexity of a rocket engine," Packard said. "There are lots of tiny wires and tubes...it's not the kind of device that a seismologist wants to [mess] around with."

Gyroscopes in space

Just as superfluid gyroscopes could be used to help researchers on Earth, the may also prove handy in spacecraft and planetary seismometers as well.

"The beauty of the superfluid gyroscope is that it's absolute," Packard said, adding that the devices could one day be pressed for spacecraft navigation and studying earthquakes on other planets. "It has an uncanny knowledge of the absolute inertial position."

But Packard conceded that there is still much to be done, not the least of which is determining the fundamental sensitivity of a helium-4 based gyroscope would be, then incorporating it into a commercially available cryogenic cooler.

Current commercial cryogenic coolers, for example, generate their own vibrations, which could contaminate the measurements of a sensitive superfluid gyroscope.

"So there is the need to filter that out," Packard said. "But I think that's a straightforward engineering task."

Tariq is the award-winning Editor-in-Chief of Space.com and joined the team in 2001. He covers human spaceflight, as well as skywatching and entertainment. He became Space.com's Editor-in-Chief in 2019. Before joining Space.com, Tariq was a staff reporter for The Los Angeles Times covering education and city beats in La Habra, Fullerton and Huntington Beach. He's a recipient of the 2022 Harry Kolcum Award for excellence in space reporting and the 2025 Space Pioneer Award from the National Space Society. He is an Eagle Scout and Space Camp alum with journalism degrees from the USC and NYU. You can find Tariq at Space.com and as the co-host to the This Week In Space podcast on the TWiT network. To see his latest project, you can follow Tariq on Twitter @tariqjmalik.