Runaway Stars Go Ballistic

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

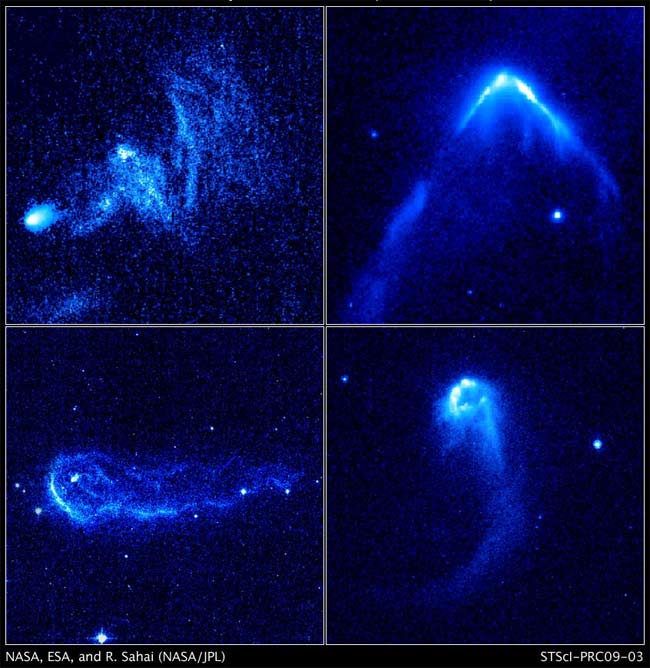

LONG BEACH,Calif. ? A total of 14 young stars racing through clouds of gas like bullets,creating brilliant arrowhead structures and tails of glowing gas, have beenrevealed by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope. They represent a new type of runawaystars, scientists say.

Thediscovery of the speedy stars by Hubble,announced here today at the 213th meeting of the American Astronomical Society,came as something of a shock to the astronomers who found them.

"Wethink we have found a new class of bright, high-velocity stellarinterlopers," said study leader Raghvendra Sahai of NASA's Jet PropulsionLaboratory in Pasadena, Calif. "Finding these stars is a complete surprisebecause we were not looking for them. When I first saw the images, I said 'Wow.This is like a bullet speeding through the interstellar medium.'"

Thearrowhead structures, or bow shocks,seen in front of the stars are formed when the stars' powerful stellar winds(streams of neutral or charged gas that flow from the stars) slam into thesurrounding dense gas, like a speeding boat pushing through water on a lake.

Youthfulstars

The strong stellarwinds suggest that the stars are young, just a few million years old, theteam concluded. Most stars produce powerful winds either when they are veryyoung or very old; and only very massive stars (with masses greater than 10times that of the sun) can keep generating these winds throughout theirlifetimes.

But theobjects Sahai and his team found aren't very massive, because they don't haveglowing clouds of ionized gas around them. They appear to be medium-sized starsup to eight times more massive than the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The stars'youth is also evidenced by the fact that the shapes of nebulas around dyingstars are very different from what is seen around the stars found by Hubble,and old stars are almost never found near dense interstellar clouds, as thesestars are.

Runaways

The bowshocks that the stars created in those interstellar clouds could be anywherefrom 100 billion to a trillion miles wide (the equivalent of 17 times to 170 timesthe width of our solar system, out to the orbit of Neptune).

These bowshocks indicate that the stars are traveling fast, more than 112,000 mph(180,000 kph) with respect to the dense gas they?re plowing through ? roughlyfive times faster than typical young stars.

Sahai andhis team think the young stars are runaways that were jettisoned from the clustersthey were born in.

"Thehigh-speed stars were likely kicked out of their homes, which were probablymassive star clusters," Sahai said.

There aretwo possible scenarios for how this stellar expulsion could have happened: Oneway is if one star in a binary system exploded as a supernova and the partnergot kicked out. Another is a collision between two binary star systems or abinary system and a third star. One or more of these stars could have picked upenergy from the interaction and escaped the cluster.

Assumingthe youthful phase of the stars lasts only for a million years and that thestars are traveling at 112,000 mph, they have traveled about 160 light-years,Sahai said.

Tip ofthe iceberg

The starsspotted by Sahai and his team aren't the first stellar runaways astronomershave found. The Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS) spied a fewsimilar-looking objects in the late 1980s.

But thosestars produced much larger bow shocks that the stars found by Hubble,suggesting they are more massive stars with? more powerful stellar winds.

"Thestars in our study are likely the lower-mass and/or lower-speed counterparts tothe massive stars with bow shocks detected by IRAS," Sahai said. "Wethink the massive runaway stars observed before were just the tip of theiceberg. The stars seen with Hubble may represent the bulk of the population,both because many more lower-mass stars inhabit the universe than higher-massstars, and because a much larger number are subject to modest speedkicks."

Theserenegade stars aren't easy to find though because "you don't know where tolook for them because you cannot predict where they will be," Sahaiexplained. "So all of them have been found serendipitously, including the14 stars we found with Hubble."

Sahai andhis team were actually looking for pre-planetary nebulas, the puffed-up agingstars on the verge of shedding most of their layers to become glowing planetarynebulas.

Theastronomers are planning follow-up studies to search for more interlopers, aswell as study what effect they have on the gas surround them.

"Oneof the questions that these very showy encounters raise is what effect theyhave on the clouds," said study team member Mark Morris of the University of California, Los Angeles. "Is it an insignificant flash in the pan, or do thestrong winds from these stars stir up the clouds and thereby slow down theirevolution toward forming another generation of stars?"

- Video:When Stars Collide

- Vote: The Best of theHubble Space Telescope

- Top 10Star Mysteries

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.