Strange Weather on Alien Planets Explained

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Though scientists have yet to find alien life on distantexoplanets, much about those planets certainly seems alien ? especially theweather.

Now researchers have developed a model that can explain someof the bizarre weather patterns seen on otherworlds.

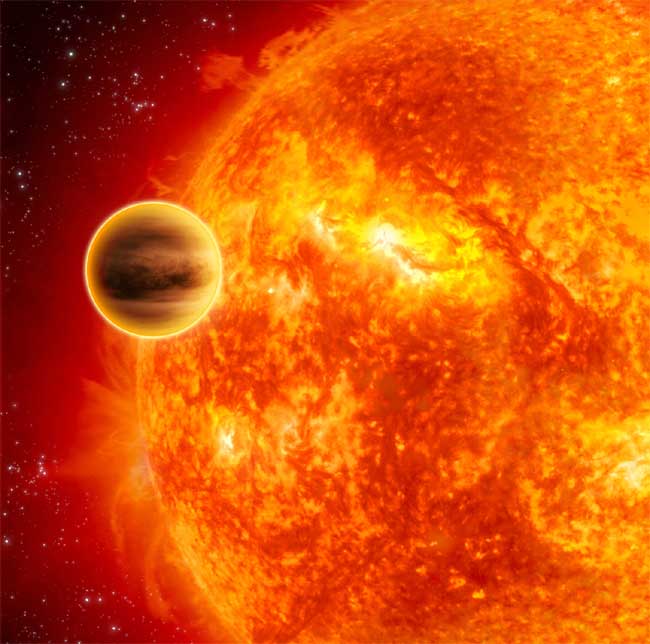

Many of the roughly 300extrasolar planets discovered so far are called "hotJupiters" because they are large gas giants like our own Jupiter.Often, these planets orbit much closer to their stars than Jupiter does to thesun, so their daylight temperatures can reach 3,000degrees Fahrenheit (1,600 degrees Celsius) ? much hotter than any planetin our solar system.

While many extrasolar planets aretoo far away to detect anything at all about their weather, for a few planetsscientists have been able to infer temperature changes from the varyingbrightness of the planet as it rotates relative to the Earth.

On one such planet, called HD189733b, Spitzer Space Telescope observations showed the night-side temperatureexceeds 1,300 Fahrenheit, which is much warmer than scientists expected.

Because many exoplanets orbit soclose in to their stars, scientists think they are often "tidallylocked," or trapped in position with one side permanently facing thestar's light and the other side in perpetual nighttime. Somehow, heat getstransported from the daytime to the nighttime side of the planets, though howthis happens has not been understood.

Now a new model created by AdamShowman of the University of Arizona and his team finally explains theprocesses creating the exotic weather patterns seen on exoplanets.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Our model I think isthe most realistic in the sense that it includes not only the weather processesin the atmosphere but couples them to how heat is absorbed and lost,"Showman told SPACE.com. "We created a pretty good representationthat matches the observations."

The researchers found thatfast-moving jet streams could carry warm air from the sunny side to the darkside of a planet. To account for the temperatures measured on planets such asHD 189733b, these streams would have to be speeding along at 7,000 mph (11,000kph).

"You're talking about windsfast enough to carry you in a hot air balloon from San Francisco to New York in25 minutes," Showman said.

While jet streams occur on planetsin our solar system, including Jupiter and Earth, the streams are generallysmaller and slower-moving than what's not being suggested for exoplanets.

"The basic chemical and physical processes are similar,but all the details are different," Showman said. "These planets areso close to their stars, so their temperatures are much higher and winds speedsare much higher. These types of jet streams are something that doesn?t exist inour solar system."

While the strange weather patternson some exoplanets would certainly be fascinating to see up close, theywouldn't be very hospitableto life like us.

"Hot Jupiters are prettycrazy places," Showman said. "Expect supersonic winds anddayside temperatures hot enough to melt lead and rocks. Only problem is, if youtried to visit, you'd be fried to a crisp before you could enjoy theview."

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- Video: Planet Hunter

- The Worst Weather in the Solar System

Clara Moskowitz is a science and space writer who joined the Space.com team in 2008 and served as Assistant Managing Editor from 2011 to 2013. Clara has a bachelor's degree in astronomy and physics from Wesleyan University, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. She covers everything from astronomy to human spaceflight and once aced a NASTAR suborbital spaceflight training program for space missions. Clara is currently Associate Editor of Scientific American. To see her latest project is, follow Clara on Twitter.