Report Urges U.S. to Pursue Space-Based Solar Power

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

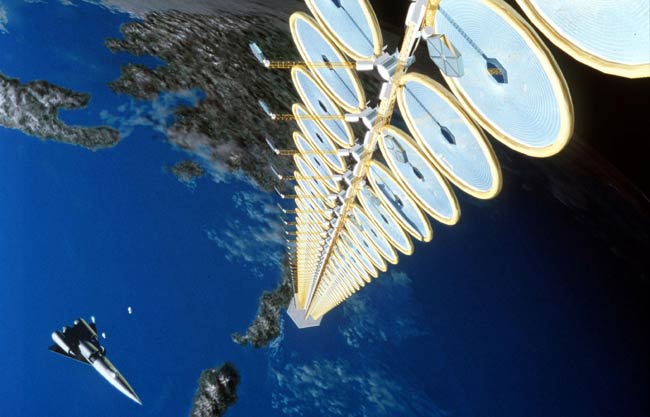

WASHINGTON — A Pentagon-chartered report urges the United States to take the lead in developing space platforms capable of capturing sunlight and beaming electrical power to Earth.

Space-based solar power, according to the report, has the potential to help the United States stave off climate change and avoid future conflicts over oil by harnessing the Sun's power to provide an essentially inexhaustible supply of clean energy.

The report, "Space-Based Solar Power as an Opportunity for Strategic Security," was undertaken by the Pentagon's National Security Space Office this spring as a collaborative effort that relied heavily on Internet discussions by more than 170 scientific, legal, and business experts around the world. The Space Frontier Foundation, an activist organization normally critical of government-led space programs, hosted the website used to collect input for the report.

Speaking at a press conference held here Oct. 10 to unveil the report, U.S. Marine Corps Lt. Col. Paul Damphousse of the National Space Security Space Office said the six-month study, while "done on the cheap," produced some very positive findings about the feasibility of space-based solar power and itspotential to strengthen U.S. national security.

"One of the major findings was that space-based solar power does present strategic opportunity for us in the 21st century," Damphousse said. "It can advance our U.S. and partner security capability and freedom of action and merits significant additional study and demonstration on the part of the United States so we can help either the United State s develop this, or allow the commercial sector to step up."

Demonstrations needed

Specifically, the report calls for the U.S. government to underwrite the development of space-based solar power by funding a progressively bigger and more expensive technology demonstrations that would culminate with building a platform in geosynchronous orbit bigger than the international space station and capable of beaming 5-10 megawatts of power to a receiving station on the ground.

Nearer term, the U.S. government should fund in depth studies and some initial proof-of-concept demonstrations to show that space-based solar power is a technically and economically viable to solution to the world's growing energy needs.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Aside from its potential to defuse future energy wars and mitigate global warming, Damphousse said beaming power down from space could also enable the U.S. military to operate forward bases in far flung, hostile regions such as Iraq without relying on vulnerable convoys to truck in fossil fuels to run the electrical generators needed to keep the lights on.

As the report puts it, "beamed energy from space in quantities greater than 5 megawatts has the potential to be a disruptive game changer on the battlefield. [Space-based solar power] and its enabling wireless power transmission technology could facilitate extremely flexible 'energy on demand' for combat units and installations across and entire theater, while significantly reducing dependence on over-land fuel deliveries."

Although the U.S. military would reap tremendous benefits from space-based solar power, Damphousse said the Pentagon is unlikely to fund development and demonstration of the technology. That role, he said, would be more appropriate for NASA or the Department of Energy, both of which have studied space-based solar power in the past.

The Pentagon would, however, be a willing early adopter of the new technology, Damphousse said, and provide a potentially robust market for firms trying to build a business around space-based solar power.

"While challenges do remain and the business case does not necessarily close at this time from a financial sense, space-based solar power is closer than ever," he said. "We are the day after next from being able to actually do this."

Damphousse, however, cautioned that the private sector will not invest in space-based solar power until the United States buys down some of the risk through a technology development and demonstration effort at least on par with what the government spends on nuclear fusion research and perhaps as much as it is spending to construct and operate the international space station.

"Demonstrations are key here," he said. "If we can demonstrate this, the business case will close rapidly."

Charles Miller, one of the Space Frontier Foundation's directors, agreed public funding is vital to getting space-based solar power off the ground. Miller told reporters here that the space-based solar power industry could take off within 10 years if the White House and Congress embrace the report's recommendations by funding a robust demonstration program and provide the same kind of incentives it offers the nuclear power industry.

Military applications

The Pentagon's interest is another important factor. Military officials involved in the report calculate that the United States is paying $1 per kilowatt hour or more to supply power to its forward operating bases in Iraq.

"The biggest issue with previous studies is they were trying to get five or ten cents per kilowatt hour, so when you have a near term customer who's potentially willing to pay much more for power, it's much easier to close the business case," Miller said.

NASA first studied space-based solar power in the 1970s, concluding then that the concept was technically feasible but not economically viable. Cost estimates produced at the time estimated the United States would have to spend $300 billion to $1 trillion to deliver the first kilowatt hour of space-based power to the ground, said John Mankins, a former NASA technologist who led the agency's space-based solar power research and now consults and runs the Space Power Association.

Advances in computing, robotics, solar cell efficiency, and other technologies helped drive that estimate down by the time NASA took a fresh look at space-based solar power in the mid-1990s, Mankins said, but still not enough justify the upfront expense of such an undertaking at a time when oil was going for $15 a barrel.

With oil currently trading today as high as $80 a barrel and the U.S. military paying dearly to keep kerosene-powered generators humming in an oil-rich region like Iraq, the economics have change significantly since NASA pulled the plug on space-based solar power research in around 2002.

On the technical front, solar cell efficiency has improved faster than expected. Ten years ago, when solar cells were topping out around 15 percent efficiency, experts predicted that 25 percent efficiency would not be achieved until close to 2020, Mankins said, yet Sylmar, Calif.-based Spectrolab — a Boeing subsidiary — last year unveiled an advanced solar cell with a 40.7 percent conversion efficiency.

One critical area that has not made many advances since the 1990s or even the 1970s is the cost of launch. Mankins said commercially-viable space-based solar power platforms will only become feasible with the kind of dramatically cheaper launch costs promised by fully reusable launch vehicles flying dozens of times a year.

"If somebody tries to sell you stock in a space solar power company today saying we are going to start building immediately, you should probably call your broker and not take that at face value," Mankins said. "There's a lot of challenges that need to be overcome."

Mankins said the space station could be used to host some early technology validation demonstrations, from testing appropriate materials to tapping into the station's solar-powered electrical grid to transmit a low level of energy back to Earth. Worthwhile component tests could be accomplished for "a few million" dollars, Mankins estimated, while a space station-based power-beaming experiment would cost "tens of millions" of dollars.

Placing a free-flying space-based solar power demonstrator in low-Earth orbit, he said, would cost $500 million to $1 billion. A geosynchronous system capable of transmitting a sustained 5-10 megawatts of power down to the ground would cost around $10 billion, he said, and provide enough electricity for a military base. Commercial platforms, likewise, would be very expensive to build.

"These things are not going to be small or cheap," Mankins said. "It's not like buying a jetliner. It's going to be like buying the Hoover Dam."

While the upfront costs are steep, Mankins and others said space-based solar power's potential to meet the world's future energy needs is huge.

According to the report, "a single kilometer-wide band of geosynchronous earth orbit experiences enough solar flux in one year to nearly equal the amount of energy contained within all known recoverable conventional oil reserves on Earth today."

Brian Berger is the Editor-in-Chief of SpaceNews, a bi-weekly space industry news magazine, and SpaceNews.com. He joined SpaceNews covering NASA in 1998 and was named Senior Staff Writer in 2004 before becoming Deputy Editor in 2008. Brian's reporting on NASA's 2003 Columbia space shuttle accident and received the Communications Award from the National Space Club Huntsville Chapter in 2019. Brian received a bachelor's degree in magazine production and editing from Ohio University's E.W. Scripps School of Journalism.