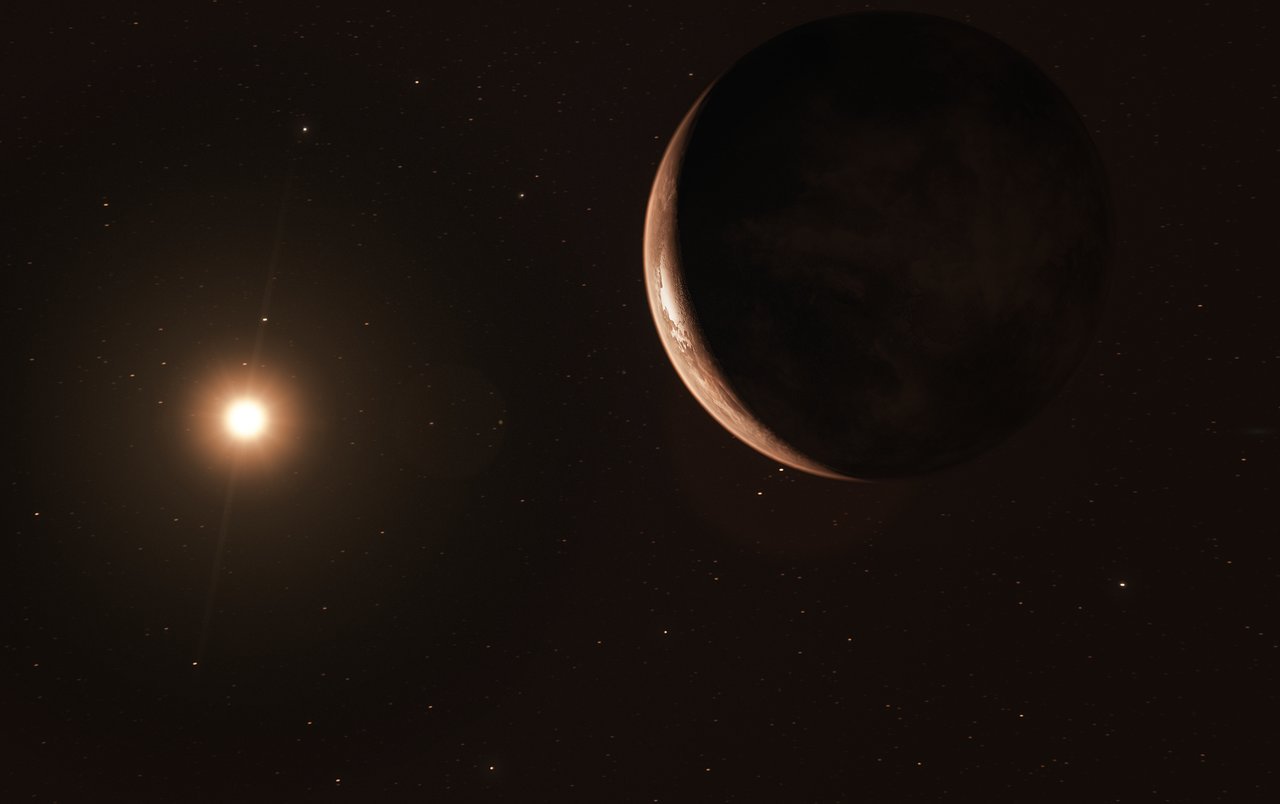

Barnard's Star Planet May Not Be Too Cold for Life After All

SEATTLE — One of Earth's nearest exoplanet neighbors, the planet orbiting Barnard's Star, may still have a chance at hosting life, despite its frigid temperatures.

New research suggests that heat generated by geothermal processes could warm pockets of water beneath the surface of the planet called Barnard's Star b, potentially providing havens for life to evolve. Images captured by NASA's much-delayed James Webb Space Telescope could help determine if the planet is the right size for that phenomenon to occur, and instruments coming even later in the future could identify signs of life.

"This is the best-imageable planet, the best Earth-sized one," Edward Guinan, a researcher at Villanova University in Pennsylvania, told Space.com. Using 15 years of data, Guinan and his colleague Scott Engle, also at Villanova, determined that while the planet is too cold for liquid water, and thus probably for life, to exist on the surface, the world might still hold subsurface oceans, depending on how large it is. Such oceans could form only on a rocky world, but if the planet is a gas giant, all bets are off. [Barnard's Star b: What We Know About Nearby 'Super-Earth' Planet Candidate]

"If it's a super-Earth, it could have anything going on," Engle said.

The two researchers announced their results here at the 233rd annual winter meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

A gas giant or a super-Earth?

Located only 6 light-years away from Earth, Barnard's Star is the closest single star to the sun; only the triple stars of the Alpha Centauri system are closer. The nearness of Barnard's Star has encouraged many researchers to turn their instruments toward it, and in the 1970s, astronomers debated whether the dim star had a planet. It wasn't until November 2018 that researchers announced the discovery of a massive world orbiting the nearby sun.

Barnard's Star b is enormous for a rocky planet, at least 3.2 times as massive as Earth. Although its orbit is roughly the same as Mercury's, the planet is probably a freezing wasteland thanks to the dim light from the star. (If our sun were replaced by Barnard's Star, it would be only 100 times brighter than the full moon, and Earth's surface would quickly freeze.)That knowledge didn't dissuade Guinan and Engle, who were both part of the team that discovered the planet. At minus 274 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 170 degrees Celsius), the planet's temperature resembles that of Jupiter's moon Europa. With its subsurface ocean, Europa is considered one of the solar system's most potentially habitable bodies.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While Jupiter's radiation melts Europa's ice, the two researchers knew something different would be needed to produce lakes and seas beneath the ice of Barnard's Star b. So, the researchers looked at the planet itself.

"Super-Earths may have a capability of having extra geothermal energy that could, if it had water ice around it, melt the ice in places," Guinan said.

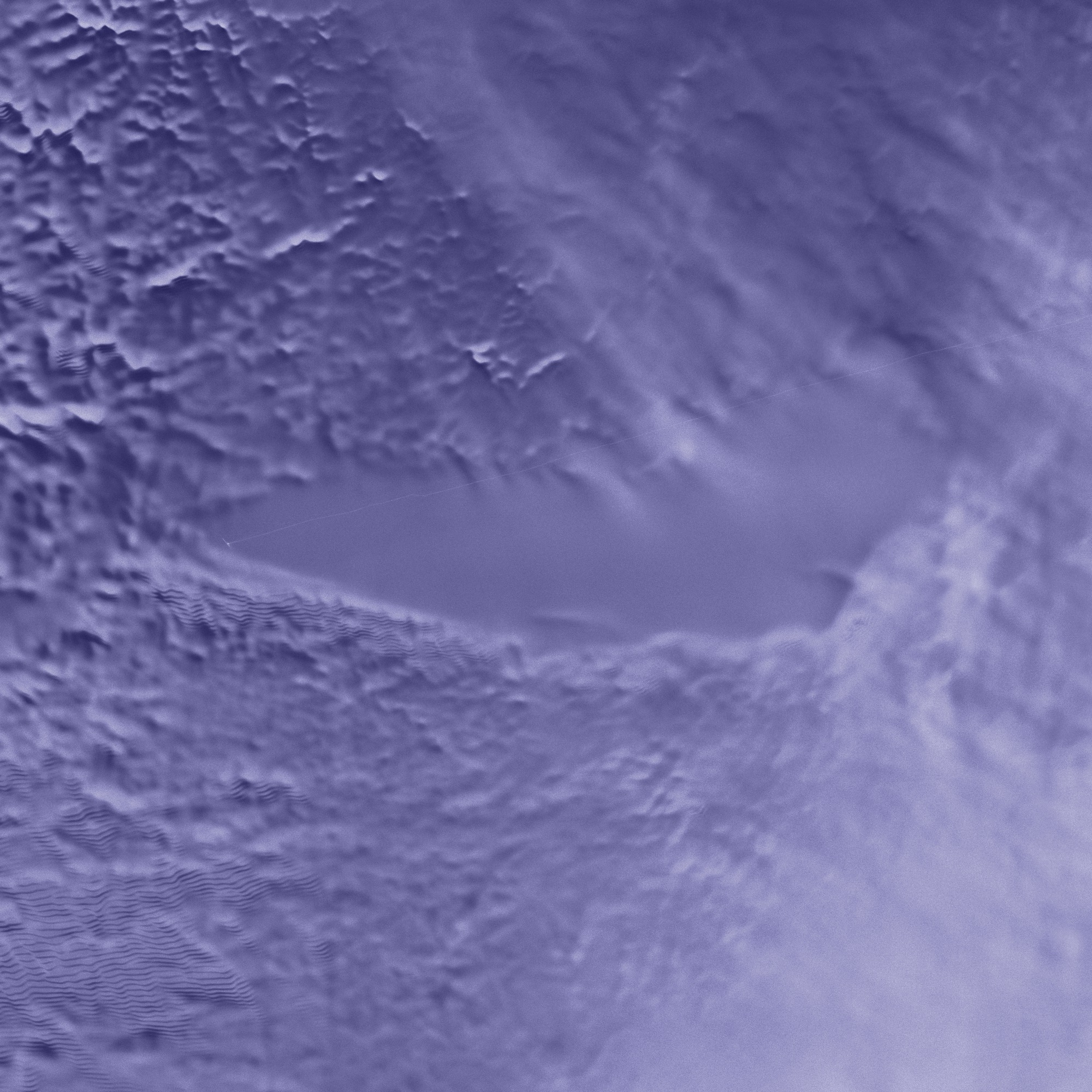

You don't have to travel to Jupiter to see evidence of similar lakes. The ice sheets of Antarctica cover hundreds of lakes, many of which are thought to be melted by the heat radiating from the Earth's core. The largest of these, Lake Vostok, is thought to contain a wide variety of organisms cut off from other life for millions of years. Guinan and Engle think similar environments could evolve on a rocky Barnard's Star b.

Rocky is the key term, because researchers aren't sure precisely how large Barnard's Star b really is — just that it's at least 3.2 times the mass of Earth. That would likely make it a rocky super-Earth, but if the planet instead has seven or eight times the mass of Earth, it would be a smaller version of Neptune. Like the solar system's own (other) blue world, this type of gas giant would lack a surface for life to evolve on and would most likely not be habitable, the researchers said.

"In that case, it's game over" in the search for life on this world, Guinan said.

The James Webb Space Telescope could help solve the mystery of the planet's nature by directly imaging the world. This kind of imaging of planets requires the worlds to be far enough away from their stars that the starlight can be blocked; otherwise, the glow would drown out the world like a spotlight drowns out candlelight.

Once again, the dim nature of Barnard's Star comes to the rescue. If the planet is a mini-Neptune, Guinan said, the Webb telescope should easily spot the world. Things are a little trickier for a rocky world, which he said was "borderline." Still, he and Engle seemed confident that the upcoming telescope could catch a glimpse.

Barnard's Star also benefits from popularity. Its close proximity to our solar system means it has been a target for planet hunters for decades, and Engle said that this world would be "on Webb's top priority list" for many researchers. If Webb spots a dim world, then it's probably a super-Earth, Guinan said. If, however, the planet is extremely bright, then it's most likely a mini-Neptune.

"Then, I don't care," Guinan said.

If life thrives beneath the icy surface of Barnard's Star b, future generations of telescopes could one day catch a glimpse of signs of that life. If the planet expels plumes, as Europa has occasionally done, researchers could search for organic material in those fountains. But that would require telescope technology that won't come until future decades.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and onFacebook. Original article on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky