Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

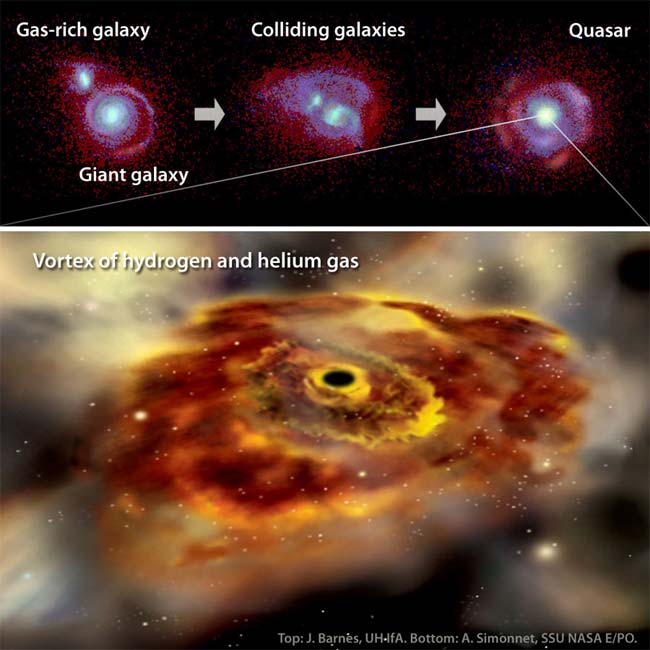

Astronomers have found the first direct evidence that some quasars fuel their bright energy emissions by feeding on gas from external sources, probably neighboring galaxies.

Hai Fu and Alan Stockton of the University of Hawaii, using the Hubble Space Telescope, observed that the chemistry of the vortex of gas responsible for a quasar's brightness (which matches that of a trillion suns) suggests that the gas comes not from the massive galaxy containing the quasar, but from a nearby smaller galaxy in the process of merging with the large one.

Outed by radio waves

Discovered in 1961, quasars consist of supermassive black holes, each surrounded by a vortex of gas. The gas spins with increasing speed as it falls toward the black hole and experiences ever greater gravitational pull. The spinning causes the gas vortex's temperature to rise until it shines hundreds of times brighter than the galaxy in which it resides.

Quasars first attracted notice for their odd output of radio waves, which at the time were thought to accompany only certain exploding galaxies and supernova remnants. The radio waves enabled scientists to determine that these objects were not stars, as had been thought, but rather powerful emissions from extremely distant galaxies.

Some of the light emitted by older quasars dates back to the early days of the universe. Research into quasars has helped astronomers develop a picture of galaxy formation in the first billion years after the Big Bang.

Though the mechanics of quasars had been observed indirectly, Fu and Stockton sought to discover the nature of the gas that fuels these hungry titans.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Graduate student Fu noticed that among certain quasars, those with an extended region of gaseous emissions as large as the galaxy itself, gas near the black hole was unusually low in the heavier elements and made up almost purely of hydrogen and helium.

"[Fu] approached me, and we looked at a few other objects together and saw the same thing," Stockton told SPACE.com. "Those quasars with extended emissions regions lacked an abundance of heavy elements, and … those without extended emissions had the usual abundance."

Eating off neighbor's plate

Their observations implied that the extended emissions quasars were picking from their neighbor's plate. "We're pretty confident that the gas in the inner region is not from this massive galaxy," said Stockton. "It came from an external source, most likely a medium-sized galaxy merging with this large one."

Their findings do not shed light on the eating habits of all quasars. Only those with extended emissions regions, which also happen to be powerful radio sources, exhibit the phenomenon. "And only a third to one half of those," said Stockton.

"We think that when the radio source ignites, it sends a blast wave out that clears out a lot of the gas [which contains heavy elements]," making way for in-falling matter from the colliding gas-rich galaxy.

The new research, published in the Aug. 1 issue of the Astrophysical Journal, will help scientists develop theories about a younger universe. The emissions observed by Fu and Stockton are an average 3 billion years old, about a quarter of the way back in time to the Big Bang.

- VIDEO: Black Hole Diving

Top 10 Strangest Things in Space

Top 10: The Wildest Weather in the Galaxy