After Pluto, New Horizons Probe Draws Near to Its Next Target: Ultima Thule

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Don't sleep on NASA's New Horizons spacecraft.

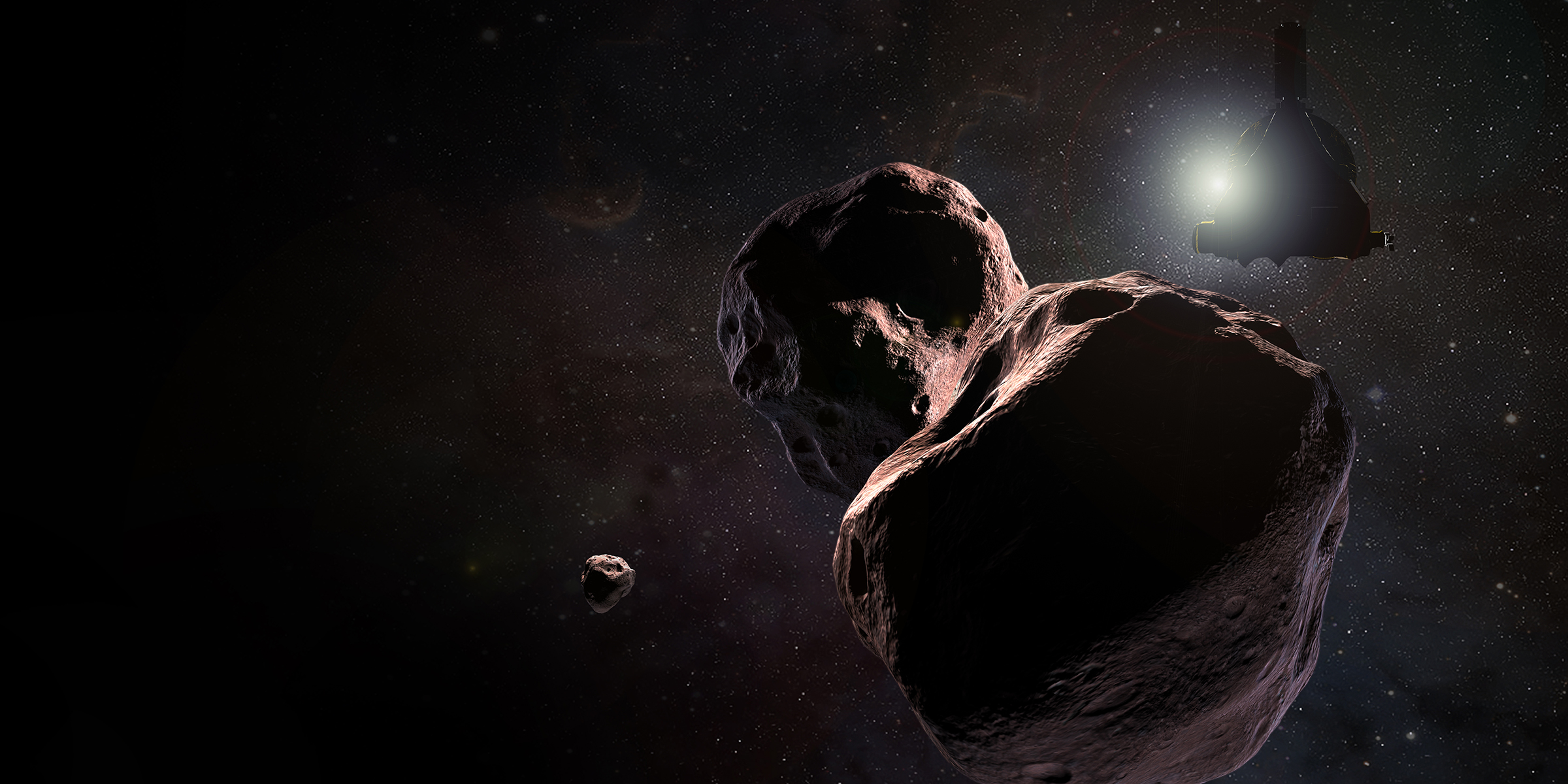

The history-making probe, which famously zoomed past Pluto in July 2015, is closing in on its next flyby target, a frigid chunk of ice and rock about 4 billion miles (6.4 billion kilometers) from Earth dubbed Ultima Thule.

New Horizons is now just 80 million miles (130 million km) from Ultima Thule, mission members said Wednesday (Sept. 19). That's less than the distance from Earth to the sun (about 93 million miles, or 150 million km). [Destination Pluto: NASA's New Horizons Mission in Pictures]

The spacecraft has already begun photographing Ultima Thule for navigation purposes and remains on track to cruise within a mere 2,200 miles (3,540 km) of Ultima in the wee hours of Jan. 1, 2019. The data New Horizons gathers during that encounter hshould shed considerable light on the solar system's early days, said mission principal investigator Alan Stern.

"Ultima Thule was formed at the origin of our solar system, and it's been in this deep freeze ever since," Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said during a webcast event Wednesday.

"Going to it is like making an archaeological dig into the history of our solar system," he added. "We've never been to anything like this."

Ultima Thule was discovered in 2014 (and is formally known as 2014 MU69). The object's surface is reddish and dark — about as reflective as potting soil, Stern said. And Ultima Thule appears to be about 23 miles (37 km) wide.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But the object remains shrouded in mystery. Its composition and shape are unknown, for example, as is its precise orbit. Researchers don't know for sure if Ultima Thule has any moons or debris rings or even if it's a single object. Indeed, Ultima may well consist of a pair of close-orbiting bodies, New Horizons team members have said.

The upcoming flyby will clear up such questions. But pulling off the epic encounter won't be easy, Stern stressed Wednesday.

Ultima Thule lies 1 billion miles (1.6 km) beyond Pluto and is much smaller than the dwarf planet. New Horizons is 3 years older now, with lower power levels. And the probe will attempt to get much closer to Ultima on Jan. 1 than it ever got to Pluto. (The 2015 encounter had a close-approach distance of 7,800 miles, or 12,550 km.)

"Everything about this flyby is tougher," Stern said.

New Horizons will have one shot at the flyby, which will occur as the probe is zooming along at about 32,000 mph (51,500 km/h). Stern said he thinks the team and the spacecraft are up to the challenge. But, as in the rest of life, there are no guarantees, especially given the boundary-pushing nature of this mission.

"It's really an adventure of exploration," Stern said.

The $720 million New Horizons mission launched in January 2006, tasked with lifting the veil on Pluto. The Ultima Thule encounter is the centerpiece of the probe's extended mission, which also includes the study from afar of a variety of other objects in the Kuiper Belt, the ring of icy bodies beyond Neptune's orbit.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.