What Would It Take to Land on Mercury? It's Time to Find Out, Scientists Say

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Mercury has been devoid of spacecraft companions since NASA's Messenger mission ended in 2015, and while the next mission bound for the innermost planet launches later this year, it won't arrive until 2025.

Scientists are passing the time digging through Messenger's data and planning what the new mission will bring, of course. But, they've also begun to think about what's next for the littlest planet in the solar system — and to revive dreams of finally putting a robot on its surface.

"That's going to really be unprecedented, with two spacecraft observing Mercury at once," Nancy Chabot, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, told Space.com. Chabot was referring to the BepiColombo mission, which consists of a pair of orbiters that will be launched in October. "We all know that we're going to get a lot of amazing data and make a lot of discoveries about the planet, but we also know that mission has been in development for decades." [10 Strange Facts About Mercury (A Photo Tour)]

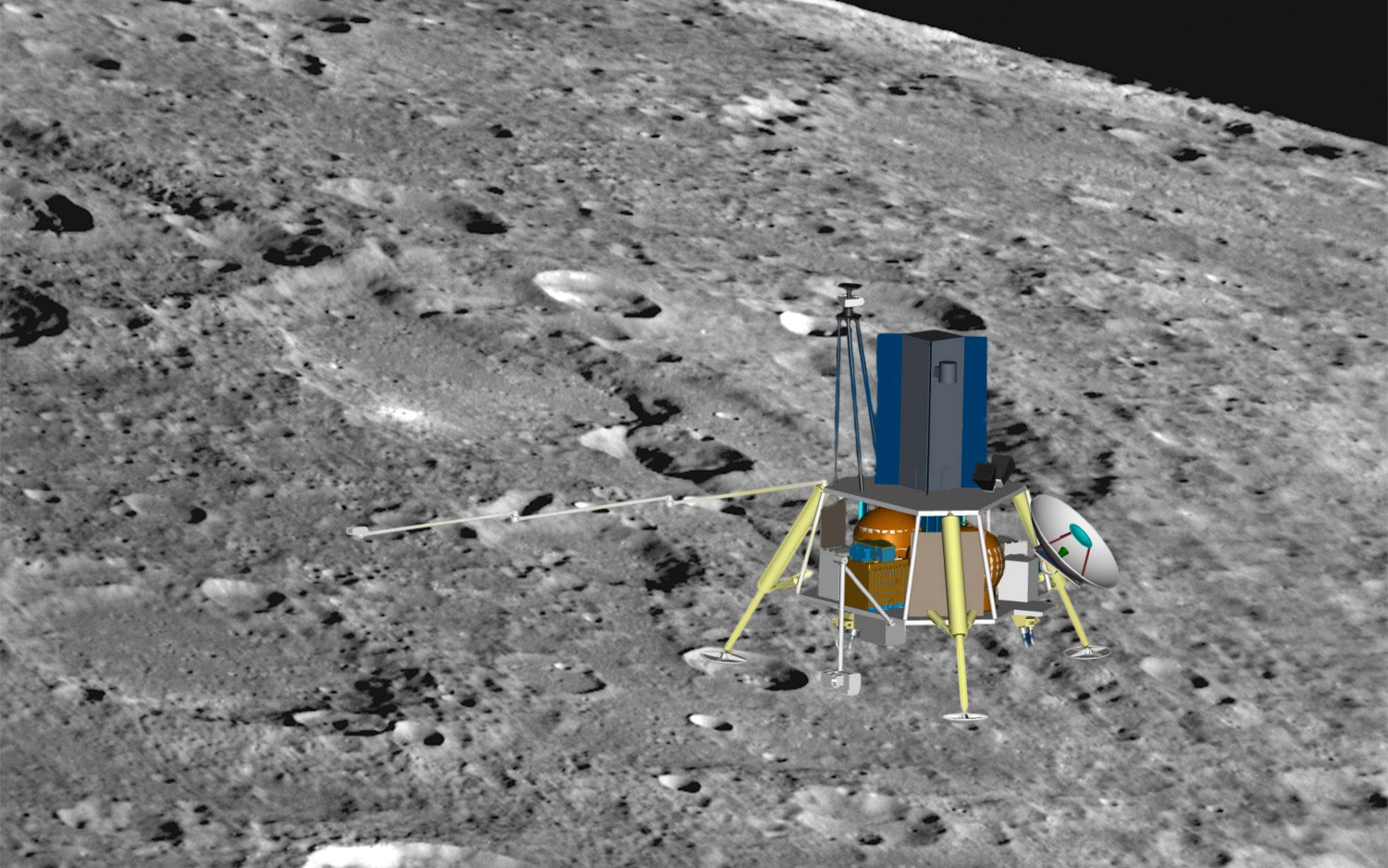

Chabot is one of the lead authors of a newly published white paper calling for a detailed study to examine the feasibility of putting a lander on Mercury. Although such a study was conducted in 2010, no mission ever came of it because the planet is such a challenging target — but new technology may make a Mercury lander more feasible. And a lander would fit with the typical rhythm of planetary exploration: fly by, orbit, land, rove.

But NASA decides its missions in accordance with reports called decadal surveys, which are produced every 10 years by the National Academies of Sciences. Committees will soon begin working on the next one for planetary endeavors, which will cover 2023 to 2032. And when they do, Mercury scientists want them to consider their favorite planet.

"We need to get working on this now for us to see a Mercury lander in the 2030s," Paul Byrne, a planetary geologist at North Carolina State University and one of the lead authors of the white paper, told Space.com. "Our job will be complete if we can convince people to do one of these studies."

Why send a lander?

There are plenty of questions haunting Mercury scientists, especially in the wake of the Messenger orbiter, which gathered data from 2011 to 2015. And that situation will only improve once BepiColombo reaches the planet in 2025 and begins sending back more orbital data.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mercury itself is a weird, wonderful world. "Mercury is sort of a planet of extremes — you've got the hot and cold temperatures, you've got the fact that it spins on its axis three times for every two times it goes around the sun," Steven Hauck, a planetary scientist at Case Western Reserve University, one of the lead authors on the white paper and a key figure in the mission study completed in 2010, told Space.com. "There are places on the planet where you can see double sunsets and double sunrises." And then there's the bit where the planet is almost entirely made up of core, with thin shells of mantle and crust surrounding a giant metallic ball.

All that weirdness means that while individual scientists have their own preferences for what a mission could look like, they say that right now, the details are much less important than looking at the feasibility of any mission at all. That's why the white paper doesn't specify any particular landing site or instrument suite — or even what the lander's primary goal would be. [Mercury Photos from NASA's Messenger Probe - Part 2 (April 2011 through 2012)]

"With any of those [mission goals], there's still amazing, compelling science that you could do on the surface of Mercury," Chabot said. "I think I'd be willing to go with a lot of different options, just because there are so many different science questions that a lander could answer."

What makes Mercury so difficult

But missions aren't solely about scientific merit: NASA and its fellow space agencies need to be pragmatic about their resources as well, and that puts Mercury at a disadvantage. "For decades, people have argued that Mercury is just as — if not more — scientifically compelling than Mars, but Mars is much easier to get to," Byrne said. Mars is also easier for a spacecraft to land on and survive, whereas every step of a Mercury lander would be challenging.

First, getting there: "You essentially need three rockets to get to Mercury," Hauck said: one to get off Earth, one to get from Earth to Mercury and one to carefully land on the planet (because it lacks an atmosphere that can slow down a spacecraft). Oh, and the entire process takes six or seven years because of the complex trajectory a spaceship would need to follow in order to reach the tiny, innermost planet.

And it doesn't get easier after landing, given a host of threats on the surface — most notably the incredible temperature extremes on the planet. "It's exceptionally hot on the day side and the exact opposite on the night side," Hauck said.

But since the last mission study was conducted in 2010, a host of new technologies have become available, or close enough for researchers to reasonably consider using them for a mission in the 2030s. That includes high-power rockets like SpaceX's Falcon Heavy, which could help send a mission on its way. And technology developed to enable the Parker Solar Probe to fly just 4 million miles (6 million kilometers) above what we consider to be the surface of the sun may be adaptable enough to allow a lander to survive out of the shade on Mercury, Byrne said.

The team's hope is that a new, detailed mission study could determine whether these factors combined, plus administrative changes — such as, no longer needing to include the cost of the launch itself in a mission plan — might make a Mercury lander affordable under NASA's New Frontiers program, which has created the Juno, New Horizons and OSIRIS-REx missions. That program caps mission costs at $850 million. [Most Enduring Mysteries of Mercury]

The group behind the white paper knows that a detailed-consideration study may not return a favorable result. "A Mercury lander is challenging, we all know this, we're not being naive," Chabot said. But the group's scientists worry that without a study, NASA will simply assume a lander isn't feasible — and in the process, shortchange the scientific merit of the smallest planet.

"We don't know why Mercury is the way it is, only that it's kind of important we understand that," Byrne said. And landing on the tiny planet may be the key to solving some of its many mysteries — if only someone can figure out how to do it.

Editor's note: This story has been corrected to clarify that the next decadal survey for planetary science covers 2023-2032.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.