Milky Weigh: New Method Pins Down Our Galaxy's Mass

Astronomers now have a much better idea of just how much the Milky Way weighs.

For the first time, researchers used the full three-dimensional motions of several nearby galaxies to obtain a new, highly accurate estimate of the Milky Way's mass. That number is 960 billion solar masses, a recent study reports.

Previous estimates had ranged from about 700 billion to 2 trillion solar masses, study team members said. [Stunning Photos of Our Milky Way Galaxy (Gallery)]

A new spin

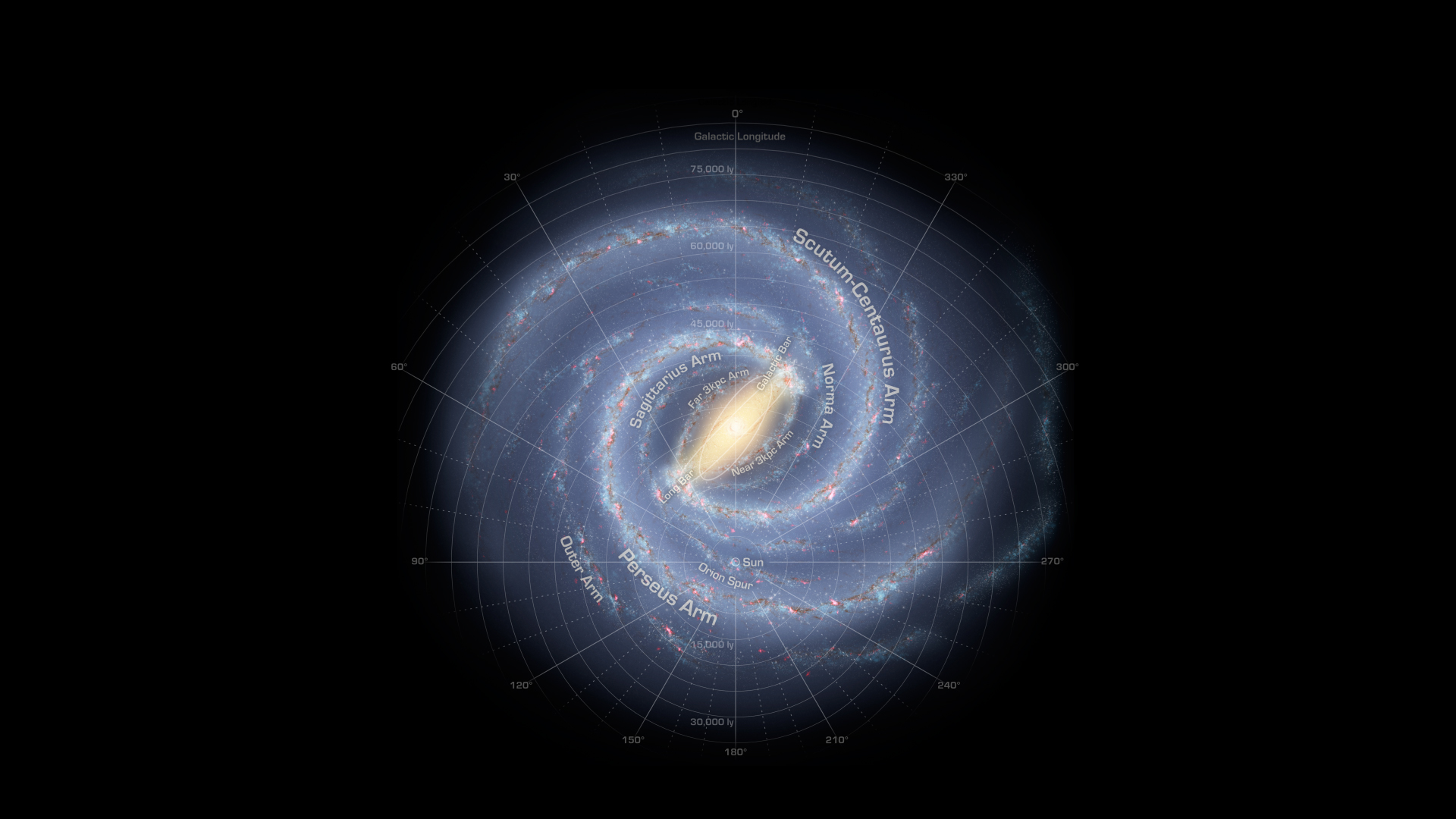

When it comes to measuring the mass of a galaxy like the Milky Way, a bathroom scale won't do, of course. Instead, astronomers have to study how the galaxy reacts gravitationally with other objects orbiting it. By charting how surrounding satellite galaxies and stellar streams move, researchers can estimate the size of our own spiral galaxy.

The recent study put a slightly different spin on this tried-and-true method. Instead of focusing on orbiting objects' position or velocity, the researchers turned their attention to the objects' angular momentum. This characteristic is more stable, team members said.

"Think of a figure skater doing a pirouette," study lead author Ekta Patel, a graduate student in the University of Arizona's astronomy department and Steward Observatory, said in a statement. "As she draws in her arms, she spins faster. In other words, her velocity changes, but her angular momentum stays the same over the whole duration of her act."

Patel and her team used 3D models of nine of the Milky Way's 50 known satellite galaxies, comparing their measured angular momentum to a simulated universe of 20,000 host galaxies resembling our own. They calculated the Milky Way's weight at 960 billion times that of the sun.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But that doesn't mean our galaxy hosts nearly a trillion stars. Astronomers think that stars, gas, dust and other "normal" stuff make up just 15 percent of the universe's mass; the rest is locked up in mysterious dark matter, which cannot be observed directly.

Most astronomers think the Milky Way hosts between 100 billion and 200 billion stars.

Smaller than Andromeda

The team's results reinforce the idea that the nearby Andromeda galaxy, also known as M31, is more massive than our own Milky Way. Understanding the Andromeda galaxy is important because the two are set to collide in 4.5 billion years. Right now, Andromeda is approaching the Milky Way at a speed of about 68 miles per second (110 kilometers per second).

According to Patel, tracking Andromeda's motion is "equivalent to watching a human hair grow at the distance of the moon."

Observations made by Europe's Gaia spacecraft and the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope in Chile, which is set to start scanning the heavens next year, will help further refine the measurements related to the satellite galaxies, providing a more precise number for their angular momentum, study team members said.

"Our method allows us to take advantage of measurements of the speed of multiple satellite galaxies simultaneously to get an answer for what cold dark matter theory would predict for the mass of the Milky Way's halo in a robust way," co-author Gurtina Besla, an astronomy professor at the University of Arizona, said in the same statement.

"It is perfectly suited to take advantage of the current rapid growth in both observational data sets and numerical capabilities," Besla added.

The study was published in April in The Astrophysical Journal. Patel also presented the results last month at the 232nd meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Denver.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky