How Solar Systems are Organized

It is the rare gas giant planet that inhabits the outskirts of its solar system. Most are like our own Jupiter and prefer to stick close to their stars, a new study suggests.

The finding, to be detailed in an upcoming issue of Astrophysical Journal, helps give astronomers a better sense of how planets are arranged in the universe at large.

“Now that we know there aren’t large numbers of giant planets lurking at large distances from their stars, astronomers have a more complete picture and can better constrain [in theory and in models] how planets are formed,” said study leader Beth Biller of the University of Arizona.

Some planet formation theories have predicted that gas giants form far away from their stars and then migrate inward by gravitational interactions with other bodies.

“There was some idea that there might possibly be a reservoir of giant planets [far from their stars] that would eventually migrate in, and we don’t really find evidence for this reservoir,” Biller said in a telephone interview.

A skewed picture?

Of the nearly 250 planets discovered so far outside our solar system, most are gas giants that orbit extremely close to their stars.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Called “hot Jupiters,” these extrasolar planets hug their parent stars tighter than Mercury does the sun. As a result, they can zip around their stars in just a few days or hours.

The majority of extrasolar planets known were found using the radial velocity method, which involves measuring the stellar wobbles caused by planets gravitationally tugging on their stars. Because this technique is best suited to detecting massive planets close to their stars (large planets located close to their stars create the biggest wobbles), astronomers were unsure whether more gas giants could be found at a greater distance from their stars via different detection methods.

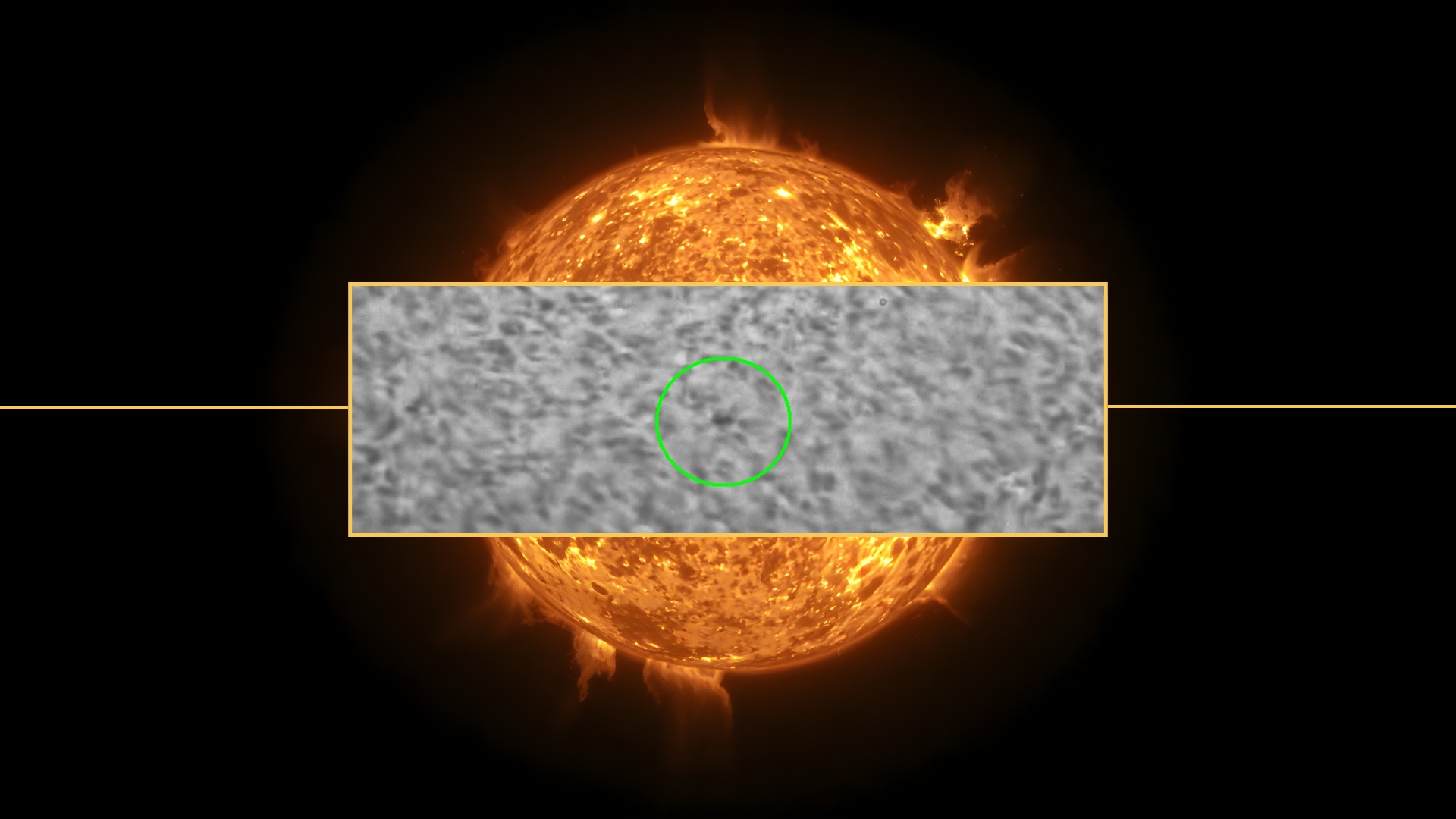

To answer this question, Biller and her colleagues conducted a three-year survey using telescopes in Arizona and Chile. The team looked specifically for gas giants residing relatively far from their parent stars. They surveyed 54 nearby, young stars where gas giant planets would still be forming. Theory predicts young Jupiters are brighter and thus easier to spot than older gas giants.

The survey turned up no giant planets beyond 10 AU (10 times the distance from Earth to the sun) of their host stars, leading the team to conclude that Jupiter-sized exoplanets are extremely rare in the outer parts of solar systems.

‘Reassuring’

Alan Boss, a planetary formation theorist at the Carnegie Institution of Washington, called the results “reassuring.”

Planets are thought to form within the dusty protoplanetary disks that surround young stars.

The two leading theories about how planets form—core accretion and disk instability—have problems making gas giants out at distances beyond 20 AU. “There just isn’t enough disk mass out there unless the disk is implausibly massive,” Boss told SPACE.com.

“Any planets formed out at those distances are probably the result of orbital interactions between unstable systems, and unstable systems are expected to form rarely, if at all,” Boss added.

Boss and Biller pointed out there is another possible explanation for the survey results.

“This survey depends on assuming that young gas giants are much brighter than older gas giants and hence easier to detect,” Boss said.

Some recent studies, however, have suggested young gas giants might not be brighter than old ones as commonly thought. If this proves to be correct, it could mean remote Jupiters do exist but are just too faint to detect.

- Top 10 Most Intriguing Extrasolar Planets

- Death Spiral: Why Theorists Can't Make Solar Systems

- On Zippy New Planets, a Year is Just Hours Long

Ker Than is a science writer and children's book author who joined Space.com as a Staff Writer from 2005 to 2007. Ker covered astronomy and human spaceflight while at Space.com, including space shuttle launches, and has authored three science books for kids about earthquakes, stars and black holes. Ker's work has also appeared in National Geographic, Nature News, New Scientist and Sky & Telescope, among others. He earned a bachelor's degree in biology from UC Irvine and a master's degree in science journalism from New York University. Ker is currently the Director of Science Communications at Stanford University.