How to See the 'Jupiter Triangle' in April's Night Sky

In many ways, stargazing is sort of like geometry. There are many star patterns that resemble a variety of different geometrical shapes. Since most of us do not have as a fertile imagination as our ancestors in visualizing people, animals, mythological beasts or even inanimate objects among the stars, we tend to fall back on more familiar figures, such as a great square, a backwards question mark, a kite, and so on.

And triangles.

The sky abounds in this particular shape. It's the easiest of all to visualize, since only three stars are needed to form it. In addition to two constellations that are officially recognized as triangles (Triangulum and Triangulum Australe, the Southern Triangle), there are triangles that represent the hindquarters of two animals, the Big Dog (Canis Major) and the Lion (Leo). [April's Night Sky: What You Can See This Month (Maps)]

And for those who are unfortunately stuck under rather light polluted skies, there is a long, narrow triangle currently visible high in the western sky during the evening, in the constellation of Gemini, the Twins. Henry Neely, who was a popular lecturer at New York’s Hayden Planetarium more than half a century ago, once noted in his 1946 book "A Primer for Stargazers": "I have always tried to indicate a figure which is much easier for star-gazers of today to find, and the three brightest and most unmistakable stars in Gemini – Pollux, Castor and Alhena – can be seen to form a long wedge."

The most famous triangle

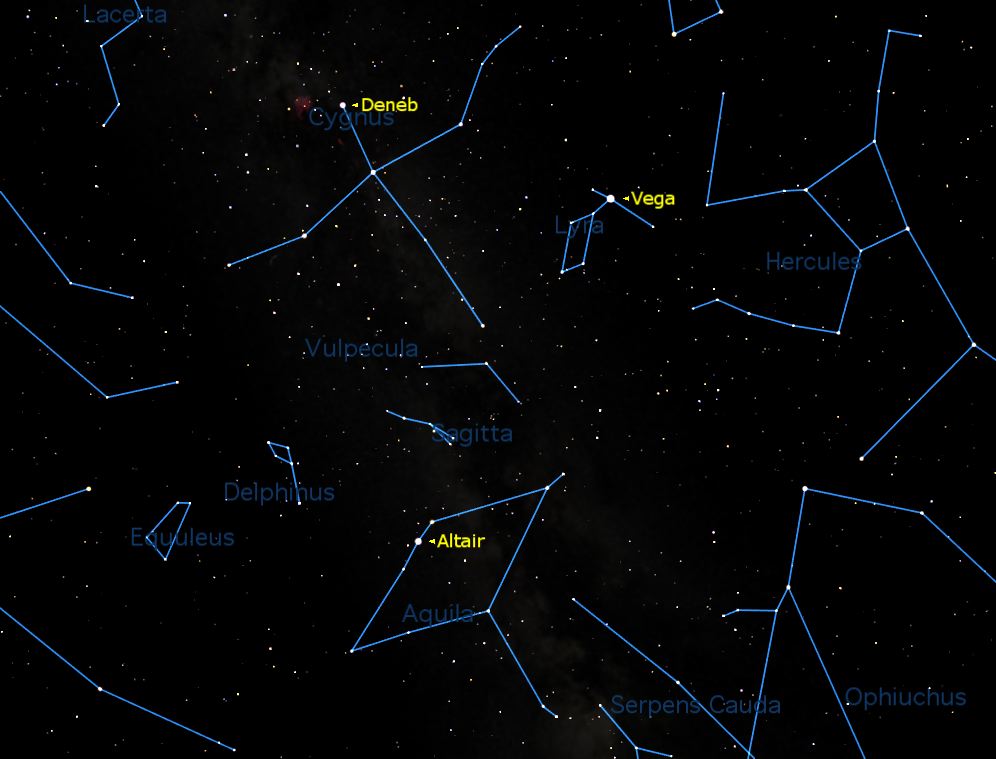

Probably the most famous celestial triangles in our sky is not a constellation in of itself, but is composed of three of the brightest stars in the sky, each from its own constellation: The Summer Triangle . It's a roughly isosceles figure composed of Vega, in Lyra, the Lyre, Altair in Aquila, the Eagle.

Currently, in order to get a good view of the Summer Triangle, we must wait until around 3 a.m. your local time and face east-northeast; the Triangle will be ascending the sky and will be roughly halfway from the horizon to the overhead point at the first light of dawn.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By the time we get to mid-June, the Triangle will already be rising as darkness falls and will be in the sky all night. And of course, during the balmy nights of July, August and September, the Triangle will be a prominent fixture in our summer sky.

But this year, there is going to be another triangle that will vie for our attention in the summertime sky.

Jupiter's triangle

In our current late evening sky, there is a somewhat similar, albeit brighter triangle configuration, although it is only temporary since one of the three points on the triangle is marked not by a star, but a planet. Facing east-southeast this week at around 11 p.m. your local time, we can see a roughly isosceles triangle formed by the bright stars Arcturus and Spica and the brilliant planet Jupiter.

Since Jupiter is the brightest of the three points, I would suggest we call it the "Jupiter Triangle."

This Triangle appears to point toward the northeast, with the brilliant yellow-orange star Arcturus (magnitude –0.1) at the vertex. The bluish star Spica (magnitude +1.0) and the brilliant planet Jupiter (magnitude –2.4) forms the bottom of the Triangle. The Arcturus-Jupiter and Arcturus-Spica sides of the Triangle measure about 38 degrees in length, while the Jupiter-Spica side is about 30 degrees long. For a reference, keep in mind that your clenched fist held at arm’s length measures roughly 10 degrees in width.

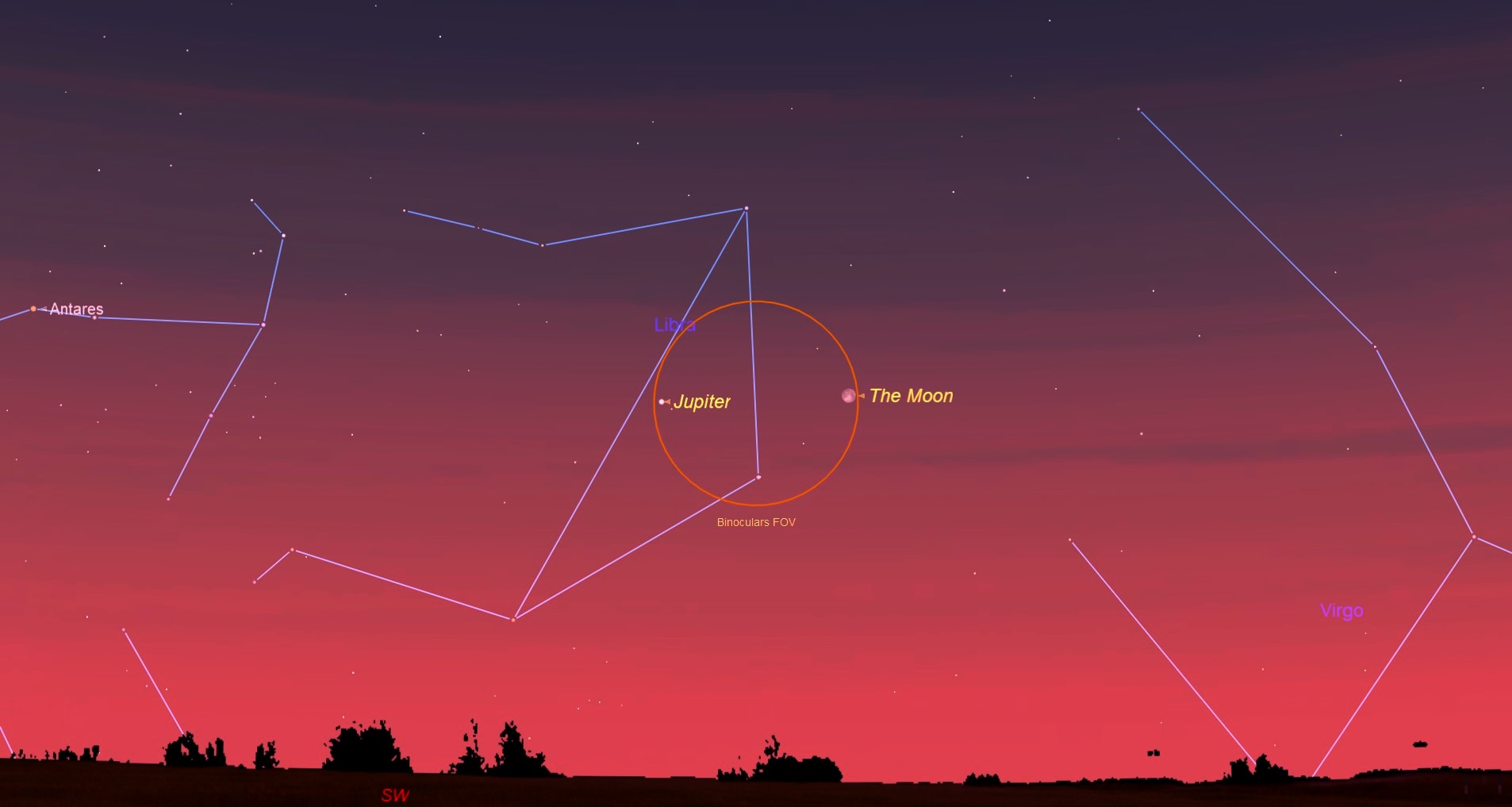

This month, on the evenings of April 28 and 29, the moon (which will be full on the later night) will be passing across the lower half of the triangle; it will be situated to the upper left of Spica on the 28 and to the upper right of Jupiter on the 29. [The Brightest Planets in April's Sky (and How to See Them) ]

Catch it while you can!

But unlike the famous Summer Triangle, which is composed of fixed stars, the Jupiter Triangle will be in a constant state of flux in the coming weeks because Jupiter will has been slowly shifting its position against the background stars. Since March 9, Jupiter has been undergoing a retrograde (backward) motion and has shifted westward against the star background. As a result, it has been approaching Spica and will continue to do so until its retrograde motion ends on July 11. By then the two will appear 20 degrees apart giving the triangle a more streamlined and slender appearance.

But thereafter, as Jupiter resumes its normal eastward motion, Spica and Jupiter will spend the rest of the summer gradually getting farther apart. Finally, during mid-to-late September, Spica will become too deeply immersed in the sunset glow to be seen. Jupiter itself will disappear into the sunset glow by early November.

When they reappear in the morning sky later in the fall, Jupiter will have moved far to the east of Spica and will no longer make for a very convincing Triangle with Spica and Arcturus … until it passes through this part of the sky again in the year 2030!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers’ Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Fios1 News in Rye Brook, NY.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.