Mysterious X-Ray Emission May Reveal Nature of Dark Matter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

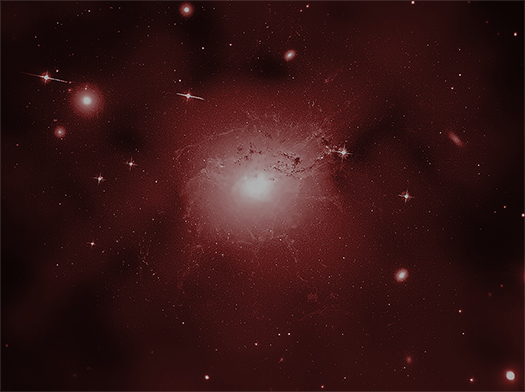

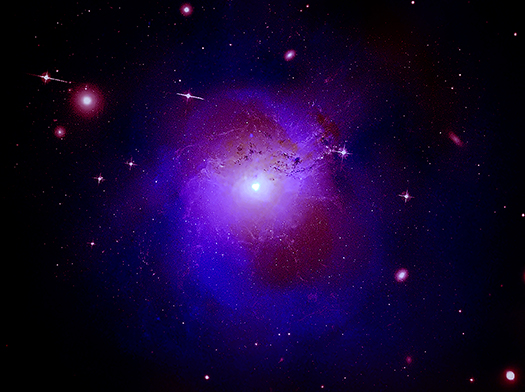

X-ray light from the Perseus cluster of galaxies may finally reveal the true nature of one of the most mysterious substances in the cosmos: dark matter.

Dark matter is a bizarre material that does not emit light or energy, yet is thought to make up about 85 percent of the matter in the universe. Researchers use creative and indirect observations to deduce dark matter's presence, but it remains challenging to pin down solid evidence of the substance's existence. Thanks to mounting observations by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, a Japanese-led X-ray telescope known as Hitomi and the European Space Agency's (ESA) XMM-Newton, scientists may be on the verge of a groundbreaking discovery about the mysterious material, researchers said in a statement from the Chandra X-Ray Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

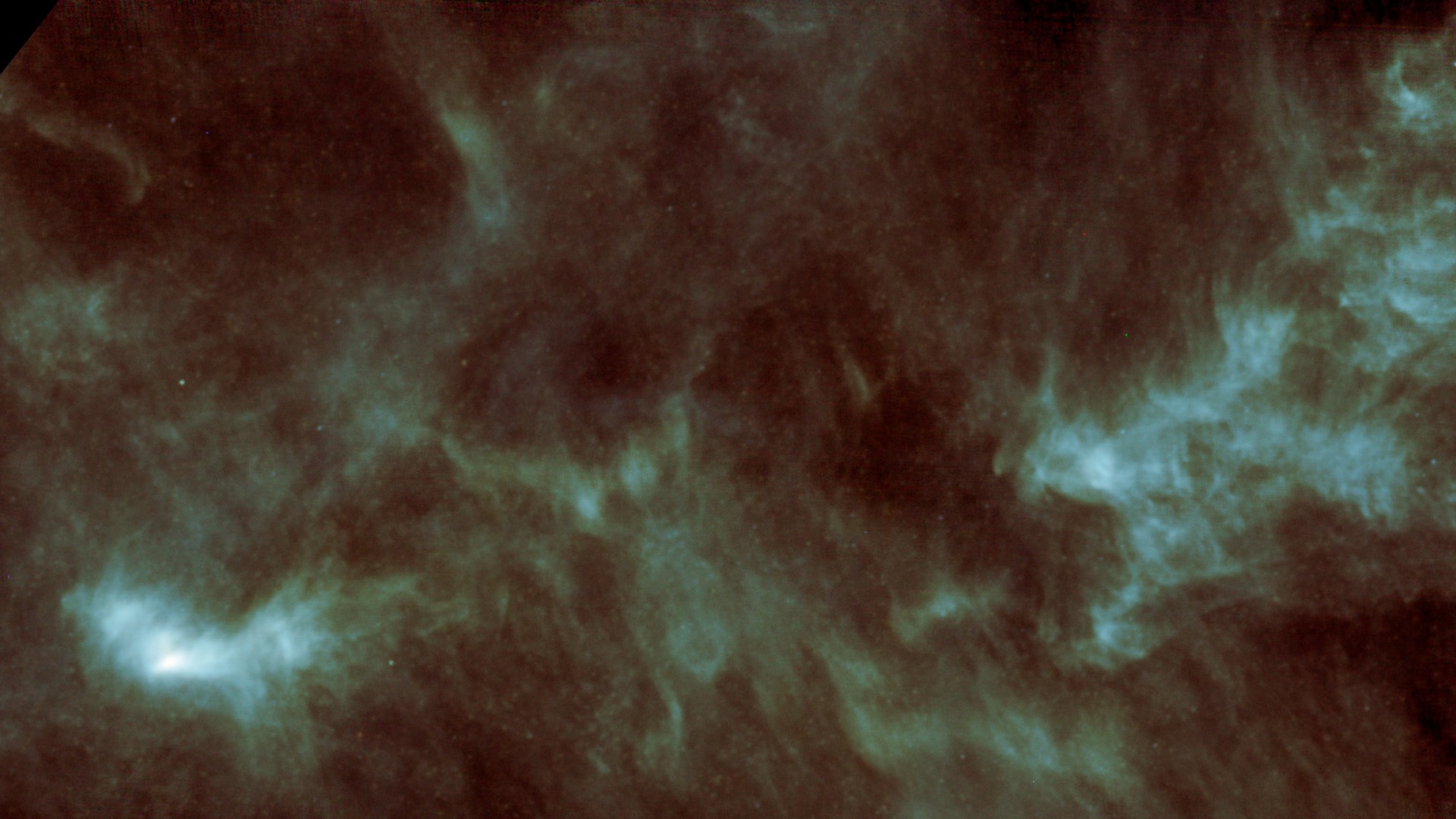

The subject of study is the Perseus cluster, a dusty region of galaxies gathered together 250 million light-years from Earth. Scientists estimate that the Perseus cluster is 11.6 million light-years across and that it may contain a whopping 660 trillion times the mass of the sun.

In 2014, an unusual spike of intensity in X-ray wavelengths caught the attention of researchers using the XMM-Newton space observatory. The waves were coming from heated gas in the Perseus galactic cluster, near the center. Researchers also found that this same wavelength of radiation, known as an emission line, was coming from 73 other galaxy clusters, according to the statement.

That 2014 observation showed radiation emanating with 3.5 kiloelectron volts (keV) of energy, and a new analysis detected an absorption of X-rays — also at 3.5 keV — surrounding a supermassive black hole at the center of the Perseus cluster. Researchers have found it nearly impossible to explain why that particular wavelength is being emitted and absorbed, and because previously-seen astronomical objects don't seem to reveal clues about the wavelength emission, they suggested dark matter could be the cause.

"We expect that this result will either be hugely important or a total dud," said Joseph Conlon of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom, lead author of the recent study. "I don't think there is a halfway point when you are looking for answers to one of the biggest questions in science." The new paper describing the team's results was published in the journal Physical Review D on Dec. 19.

If dark matter caused the atypical emission and absorption lines at that wavelength — both giving off and absorbing X-rays within the collection of galaxies — further observation could teach researchers more about the mysterious substance, the scientists said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Fortunately, powerful X-ray telescopes currently being developed will let scientists make more-precise observations of these fascinating X-ray emission lines.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.