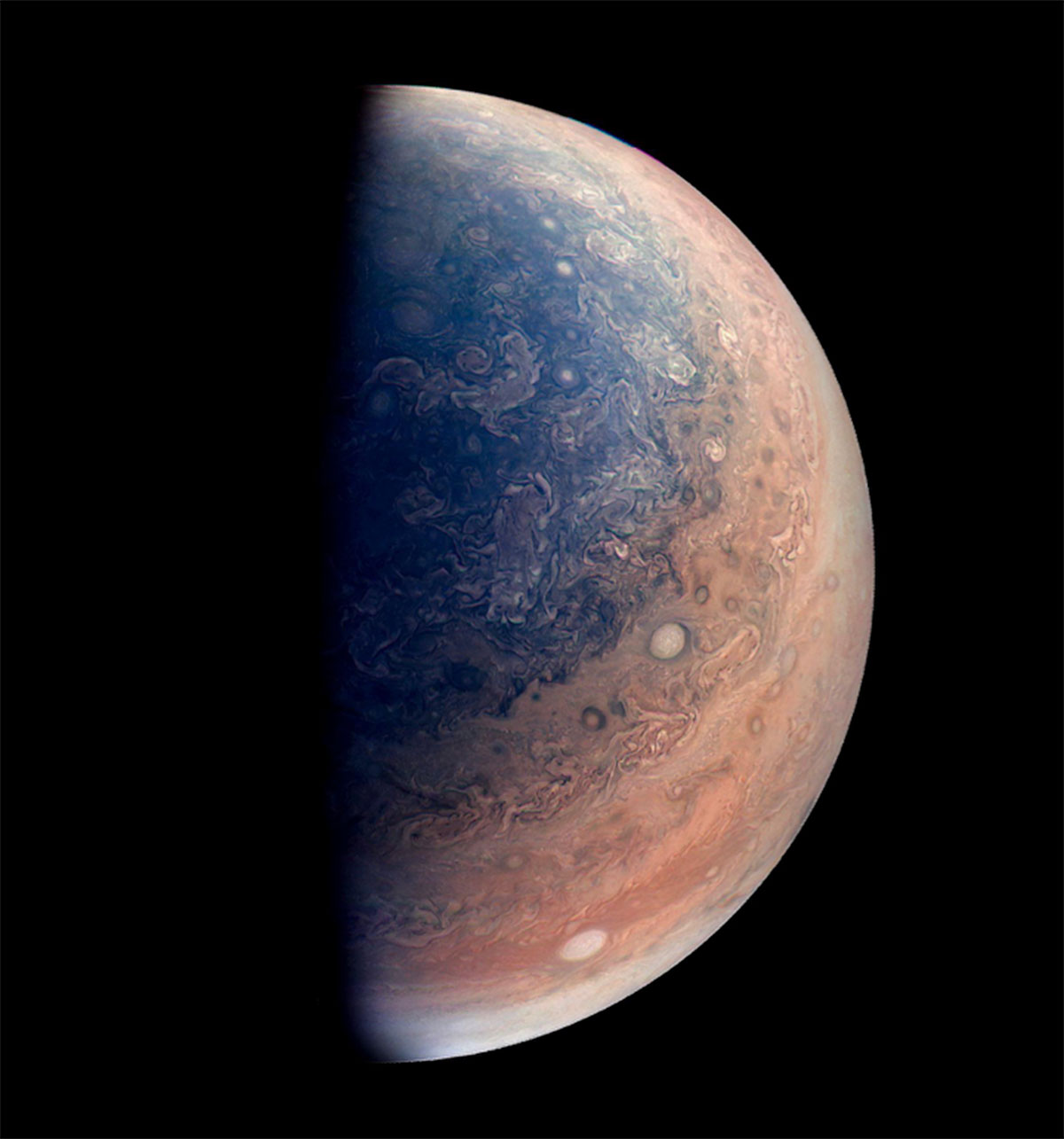

Ancient Jupiter: Gas Giant Is Solar System's Oldest Planet

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Astronomers finally know how old Jupiter is.

The gas giant's core had already grown to be 20 times more massive than Earth just 1 million years after the sun formed, a new study suggests.

"Jupiter is the oldest planet of the solar system, and its solid core formed well before the solar nebula gas dissipated, consistent with the core-accretion model for giant planet formation," lead author Thomas Kruijer, of the University of Munster in Germany and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, said in a statement. [Photos: Jupiter, the Solar System's Largest Planet]

Article continues belowAbout 4.6 billion years ago, the solar system coalesced from an enormous cloud of gas and dust. The sun formed first, and the planets then accreted from the leftover material spinning around the newborn star in a vast disc.

Theoretical work strongly suggests that Jupiter took shape quite early in the solar system's history, but the planet's precise age had remained a mystery, Kruijer and his colleagues said.

The researchers dated Jupiter's formation and growth by analyzing the ages of certain iron meteorites — shards of the metallic cores of ancient planetary building blocks — that have fallen to Earth. These ages were determined by measuring the abundances of molybdenum and tungsten isotopes. (Isotopes are versions of elements with different numbers of neutrons in their atomic nuclei.)

This work indicated that the meteorites came from two distinct "reservoirs" that were spatially separate for 2 million to 3 million years, beginning about 1 million years after the solar system formed, the researchers said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The most plausible mechanism for this efficient separation is the formation of Jupiter, opening a gap in the disk and preventing the exchange of material between the two reservoirs," the researchers wrote in the new study, which was published online today (June 12) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Jupiter's core would have to be about 20 times more massive than Earth to keep the two reservoirs from mixing, Kruijer and his team calculated. So, the results suggest the nascent gas giant was already that big within the first 1 million years of solar system history, the researchers said.

Jupiter's growth rate slowed thereafter, they said. The gas giant didn't reach 50 Earth masses until a minimum of 3 million to 4 million years after the sun's formation, the researchers determined. (Jupiter is currently about 318 times more massive than Earth.)

"Our measurements show that the growth of Jupiter can be dated using the distinct genetic heritage and formation times of meteorites," Kruijer said in the same statement.

The new study could also help explain why the solar system lacks worlds intermediate in mass between Earth and "ice giants" such as Uranus and Neptune. Such "super-Earths" are relatively common in other star systems.

"One important implication of this result is that, because Jupiter acted as a barrier against inward transport of solids across the disk, the inner solar system remained relatively mass deficient, possibly explaining its lack of any 'super-Earths,'" the researchers wrote in the new study.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.