Big Sun Storms and Little Solar Burps Have the Same Trigger

Giant eruptions of material and smaller jets from the sun's surface are closer cousins than anyone thought, according to new research from the U.K.'s Durham University and NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center. Understanding the mechanism the two have in common is a big step forward in understanding how the solar atmosphere behaves.

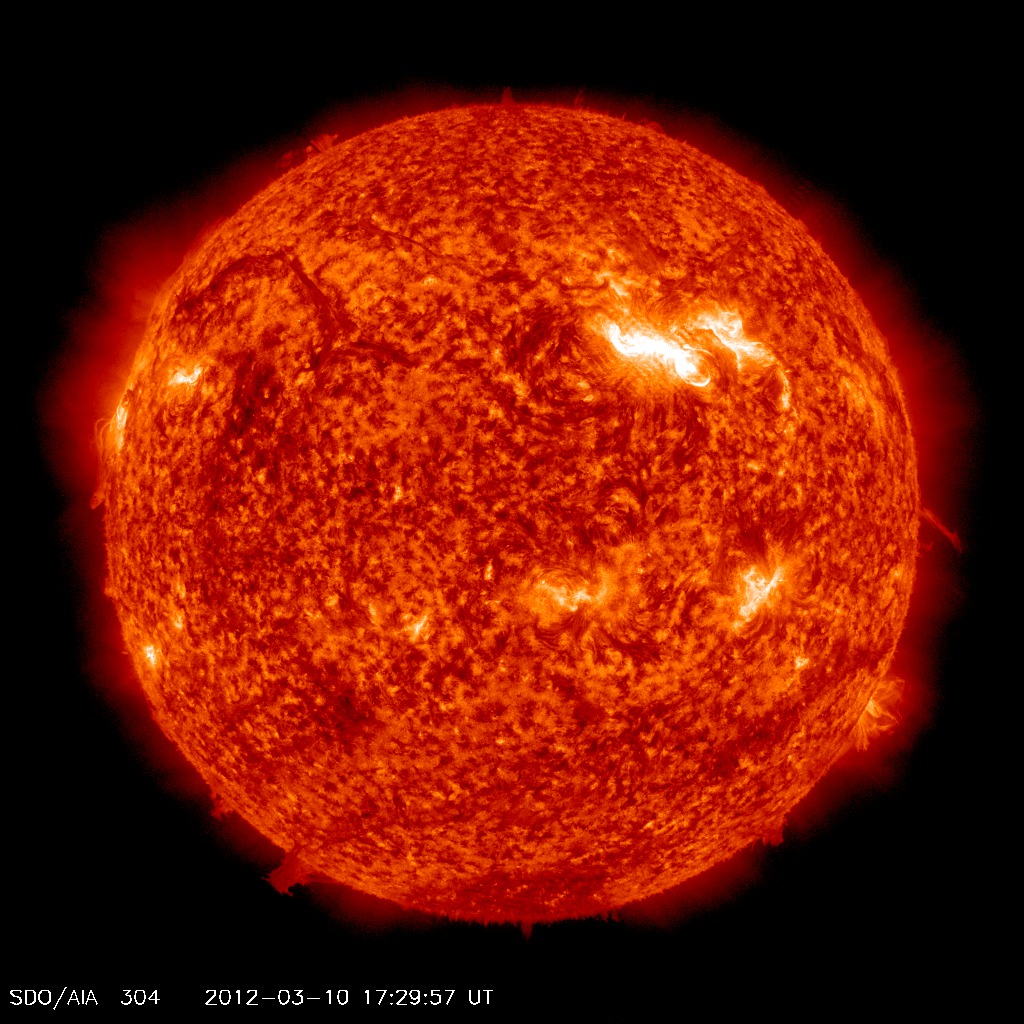

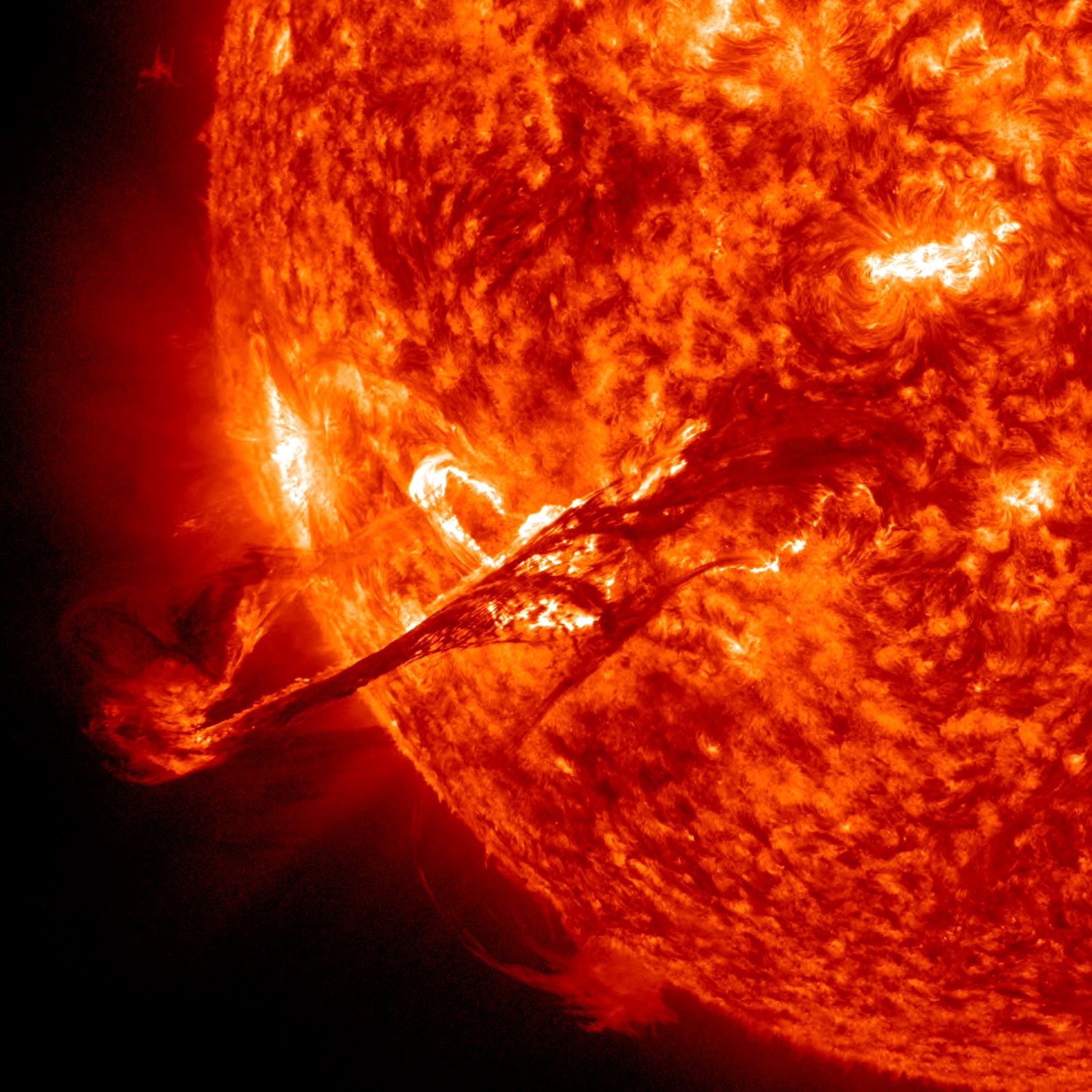

Coronal mass ejections (CMEs) and coronal jets are two types of solar activity with very different magnitudes. CMEs are blasts of charged particles that can cause widespread disruption of communications and endanger astronauts in orbit when they reach Earth, and they also generate the spectacular auroras visible from Earth's polar regions. The massive blasts occur when the magnetic field lines near the solar surface cross, break and reform or reconnect, releasing energy.

Coronal jets, on the other hand, are smaller, more frequent and much less energetic. Their origin was unknown but thought to be different than that of CMEs, researchers on the new study said in a statement, although the jets seemed related to the movement of energy to the upper atmosphere of the sun, contributing to the solar wind of charged particles that stream toward Earth. [The Sun's Wrath: Worst Solar Storms in History]

New 3D simulations of the solar atmosphere illustrate how coronal jets could occur the same way CMEs do, though on a much smaller scale. In the statement, the researchers said the strength and shape of the magnetic field around filaments of gas on the sun's surface, or photosphere, determines whether a coronal jet or a CME is produced.

The scientists call their mechanism for eruptions the "breakout model," because the stressed filament "breaks through" the local magnetic fields into space.

"The breakout model unifies our picture of what's going on at the sun," Richard DeVore, a solar physicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center and co-author on the new work, said in the statement. "We can advance understanding of how these eruptions are started, how to predict them, and how to better understand their consequences."

"A greater understanding of solar eruptions at all scales could ultimately help in better predicting the sun's activity," lead author Peter Wyper, of the department of mathematical sciences at Durham University, said in the statement. "They can interfere with satellite communications, for example, so it is beneficial for us to be able to understand and monitor this activity."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Future studies will involve more simulations, the researchers said, but only closer observations of the sun's magnetic field and flows of plasma — especially at the poles — can confirm the breakout model is correct. Those kinds of observations will have to wait for data from two upcoming missions: NASA's Solar Probe Plus and the joint European Space Agency/NASA Solar Orbiter. The Solar Probe Plus is scheduled for July 2018, while the Solar Orbiter is slated for October of that year.

The new findings were detailed today (April 26) in the journal Nature.

Follow Jesse Emspak on Twitter @Mad_Science_Guy. You can follow us @Spacedotcom and on Facebook & Google+. Original story on Space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.