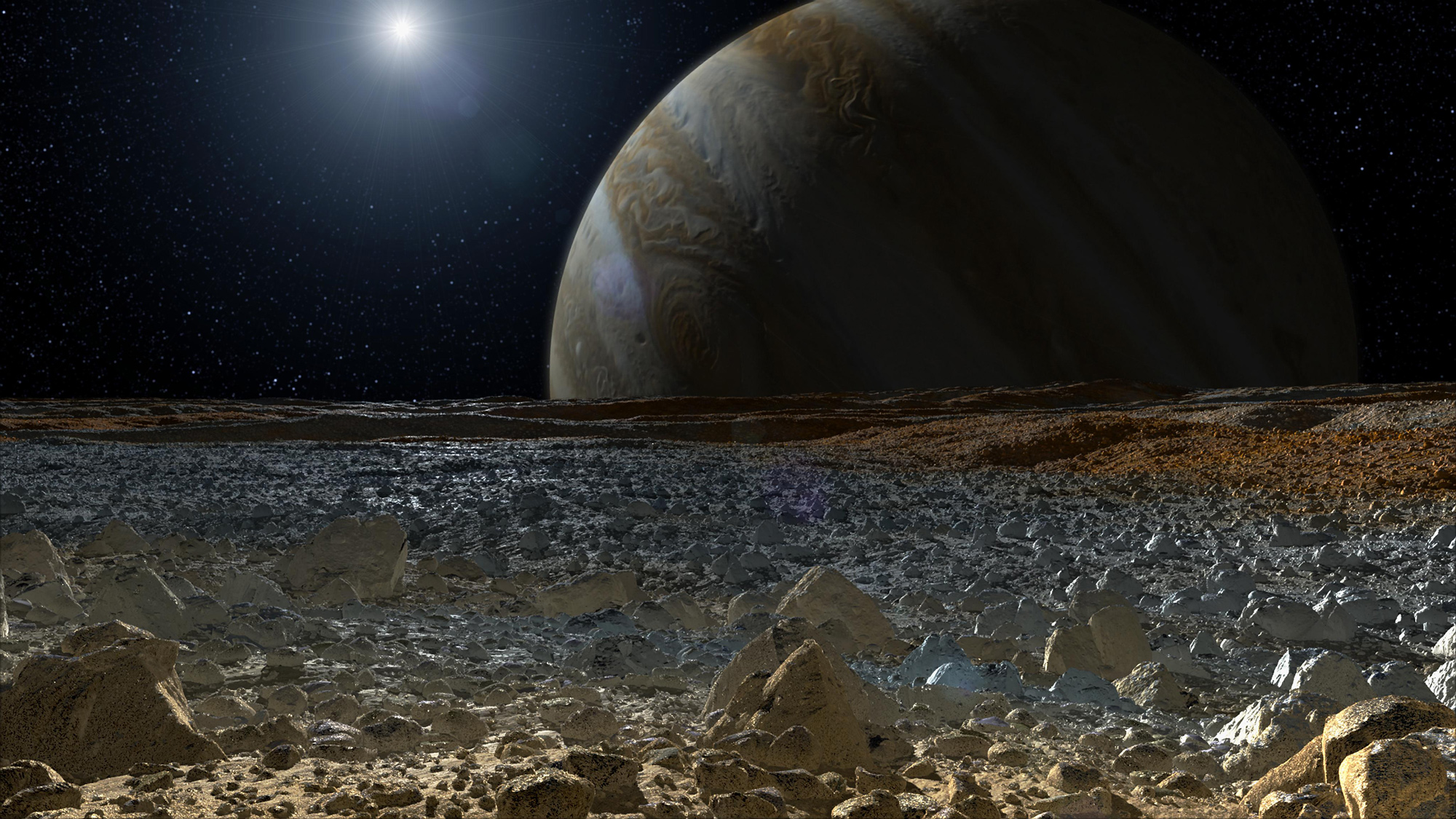

NASA's Europa Lander May Drill to Find Pristine Samples on Icy Moon

Searching for signs of life, or life's precursors, on the surface of Jupiter's moon Europa could spoil the hunt before it begins — which is why many scientists advocate going underground.

An ocean containing twice as much water as all of Earth's seas is thought to slosh beneath Europa's 10-to-15-mile-thick (15 to 25 kilometers) ice shell. For this reason, astrobiologists regard the 1,900-mile-wide (3,100 km) Jovian moon as one of the solar system's best bets to host extraterrestrial life.

Furthermore, NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has spotted evidence of water-vapor plumes emanating from Europa's south polar region, suggesting that material from the ocean may fall back onto the moon's icy surface. [Europa May Harbor Simple Life-Forms (Video)]

That's an exciting prospect for NASA, which aims to put a lander on Europa in the 2020s to look for chemical evidence that the moon could support life. (NASA's Europa mission began as a flyby-only affair, but the U.S. Congress ordered the inclusion of a lander late last year.)

−However, the very landing could complicate this search greatly. Firing thrusters to slow the spacecraft's descent "will be like hosing down the ground with ammonia, and this is a very inconvenient thing to do," said Ralph Lorenz, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland.

It's inconvenient because ammonia contains nitrogen, he said. "Everything in our body has nitrogen," Lorenz told Space.com. −−"If you are interested in nitrogen as a prerequisite for life, then finding even traces of it at Europa is important, and so even a little thruster contamination matters a lot."

If such contamination were to occur, scientists would struggle to figure out if nitrogen detected at Europa was native or imported from Earth, he said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In a study published in the journal Planetary and Space Science this past August, Lorenz found that putting a 440-lb. (200 kilograms) spacecraft down on Europa would disturb the surface out to 30 feet (9 meters) around the lander. He concluded this after studying images of past surface disturbances caused by spacecraft landings on Earth's moon and Mars.

Scientists cannot assume that the Europa lander will be able to move away from such a contaminated site. NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has wheels, so it drove away from its Red Planet landing site back in 2012. But scientists know little about the hazards on Europa's surface, Lorenz said.

"The distribution of rocks could cause a lander to tip over, or it could fall into a crevasse," Lorenz said. "In space exploration, it's not good enough to speculate that this will work. Why throw 1 [billion] or 2 billion [dollars] into it?"

The issue of nitrogen contamination on Europa is more problematic than it is on Mars or Earth's moon because the Jovian satellite is much colder than these other worlds, Lorenz said. At its warmest, temperatures on Europa don't rise above minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 160 degrees Celsius). Under such frigid conditions, ammonia is more likely to stick to Europa's surface, allowing it to interact with other molecules and perhaps make a mess of observations, Lorenz said.

Other researchers think that sampling Europa's surface is important, but that the best samples lie deeper. "We have to go down, beneath the surface," said Britney Schmidt, a planetary scientist at the Georgia Institute of Technology who has worked on NASA's Europa lander mission concept.

This means drilling into Europa's ice. Schmidt thinks a mission needs to drill at least 4 inches (10 centimeters) down, to a place where the thrusters haven't contaminated the ice and space radiation hasn't destroyed biogenic molecules — the stuff− necessary for life's processes to take place.

"If we get 10 centimeters, or a meter [about 3 feet], down, this area hasn't been blasted with the thrusters," Schmidt told Space.com. "Maybe a portion, but the confidence for getting a pristine sample goes up the further you go down."

The Europa lander won't just be looking for ammonia or nitrogen, stressed Peter Willis, a chemist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California.

Still, he said, the Europa lander mission will take precautions; the lander will likely bore into the ice, Willis said. NASA also plans to employ the sky-crane landing method, which put Curiosity down on Mars, with the Europa craft, he added. −−After descending toward Europa, a hovering spacecraft will fire thrusters into the air to stay aloft while it uses a cord to lower the lander down to the surface. Then, it will let go. [How Curiosity's Sky Crane Landing Worked (Infographic)]

In such a case, "the spacecraft actually falls, but we hope not too far," Willis said.

Limiting the amount of Earthly organics being sprayed on Europa's surface will help NASA's quest to find extraterrestrial life —− even if what researchers are looking for doesn't walk or swim, Schmidt said.

"People want us to drill into Europa and find a fish," she said. "But right now, this is not realistic;− the hope is to land there and detect biogenic molecules, the molecules essential for life."

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.