Saturn Probe Dives Past Rings for 1st Time

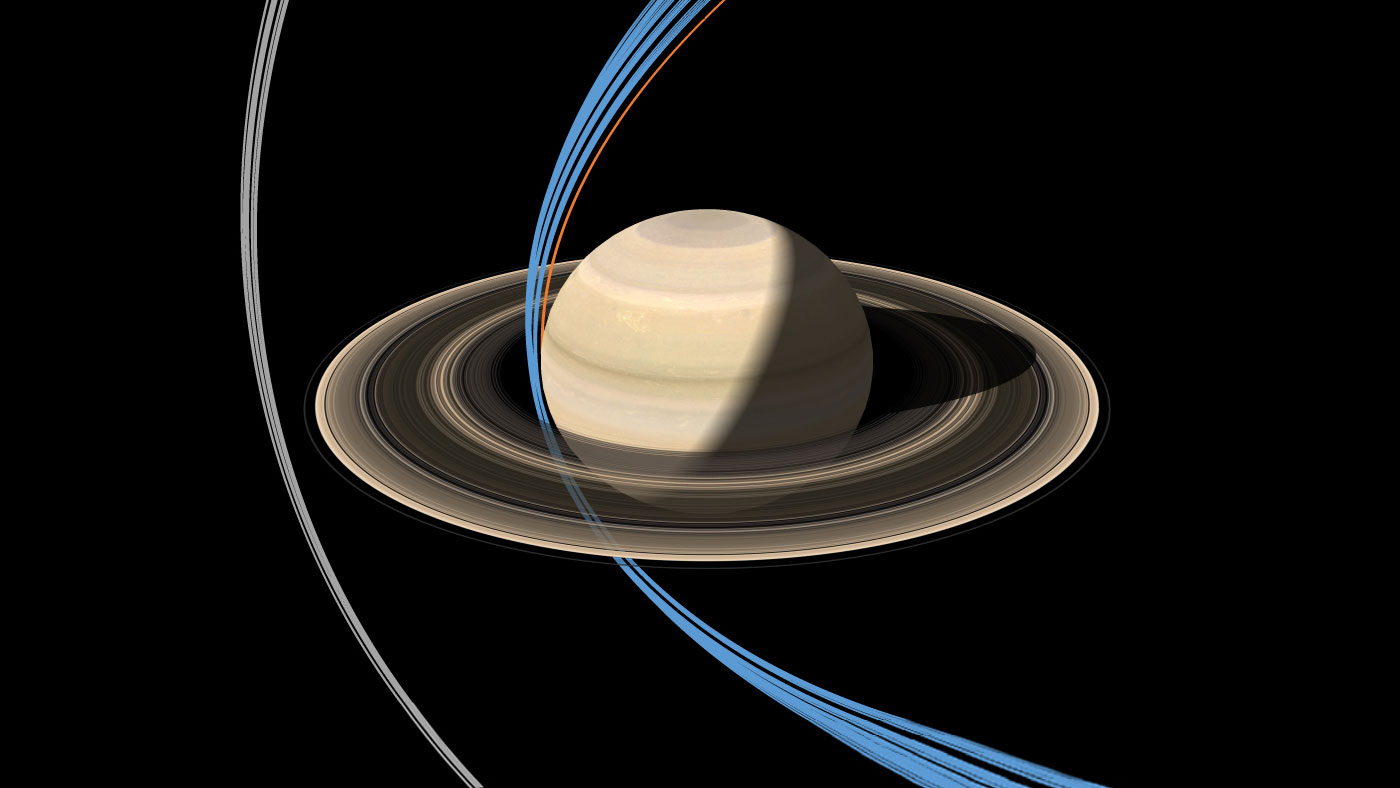

NASA's Cassini spacecraft grazed Saturn's iconic rings Sunday (Dec. 4), performing the first plunge of the long-lived mission's next-to-last phase.

Cassini zoomed within 57,000 miles (91,000 kilometers) of Saturn's cloud tops on Sunday morning, diving through the planet's ring plane at about the spot where a faint ring generated by the small moons Janus and Epimetheus lies, NASA officials said.

Cassini will perform 19 more such close passes, each one about a week apart, through April 22, 2017.

"It's taken years of planning, but now that we're finally here, the whole Cassini team is excited to begin studying the data that come from these ring-grazing orbits," Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, said in a statement. "This is a remarkable time in what's already been a thrilling journey."

The $3.2 billion Cassini-Huygens mission, a joint effort involving NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency, launched in October 1997 and arrived in orbit around Saturn in July 2004. In January 2005, the piggyback Huygens lander descended to the surface of Titan; the Cassini mothership, meanwhile, kept studying Saturn and the planet's rings and moons.

That work won't last much longer, however. On April 22, Cassini will fly close to Titan, whose gravity will reshape the probe's orbit such that it zooms between Saturn and its innermost ring, which lies just 1,500 miles (2,400 km) from the planet.

Cassini will then make 22 plunges through this gap during the "Grand Finale" phase of its mission, which will conclude with an intentional death dive into Saturn's thick atmosphere on Sept. 15, 2017.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This suicide maneuver will ensure that Cassini doesn't contaminate Titan or its fellow Saturn moon Enceladus with microbes from Earth, NASA officials have said. (Both satellites may be capable of supporting life; scientists think that both Titan and Enceladus harbor subsurface oceans of liquid water, and Titan has seas of hydrocarbons on its surface.)

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.