What Will We Do When Hubble Dies?

For a generation, the Hubble Space Telescope has been exposing the universe's deepest, darkest secrets. From imaging the volcanoes of Jupiter's moon Io, to watching the dramatic breakup of comets, imaging baby galaxies, and helping to nail down the universe's age, its data has been instrumental in today's understanding of the cosmos near and far.

But it's an old telescope, unmaintained since the last space shuttle mission visited in 2009. While the observatory is in excellent health today, it's expected to stop collecting data sometime in the 2020s. What will we lose when the telescope finally dies?

NASA is quick to point out that the James Webb Space Telescope, expected to launch in 2018, will enhance Hubble's capabilities in many ways. But for the telescope's higher resolution and ability to peer back to the very early days of the universe, there is one key thing it doesn't have: ultraviolet capabilities. (It also will lack some of Hubble's fine spectral resolution, and ability to observe a special spectral line called H-alpha that is useful for nebulae and stars.)

Astronomers are being urged to submit as many UV proposals to Hubble as possible because once it dies, there are no immediate plans to launch a successor. (Astronomers could then pull from the archive as needed in future decades.) Earth's atmosphere filters out UV, which is great for protecting life, but bad for UV astronomy, so it needs to be done from space. Astronomers say they don't think another UV telescope will fly until the 2030s, at the earliest.

RELATED: Our Universe Has 10-20 Times More Galaxies Than Thought

"For example, one of the big topics that we're going to look at in star and planet formation is the accretion of gas on to young, newly forming stars or planets," said Adam Kraus, an astronomer at the University of Texas at Austin. He explained that as gas falls on to budding stars and planets, they radiate most of their energy in the blue and ultraviolet wavelengths. Webb won't be able to see this as Hubble does, he told Seeker.

NASA's Jane Rigby, the deputy project scientist for Webb's operations, points out that the new telescope is designed to do science that Hubble can't. Webb has seven times more collecting area and also works at near absolute zero (the coldest temperature possible). Hubble works at room temperature, so it can't see as well in the infrared. Webb will see into dusty places where stars are forming, or galaxies that have been deeply "redshifted" (with spectral lines moving towards the red end of the spectrum) due to cosmic expansion.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Luckily for astronomers, it's expected that Hubble's and Webb's time in space will overlap. Hubble has a rich archive of observations that Webb could spend time looking at, including the famous "deep fields" of young galaxies. This type of work will be Webb's "bread and butter", Rigby said.

There's also the potential to make stereoscopic or "3D" images of several objects, since Hubble (in low Earth orbit) will be a million miles away from Webb, further out in space. At the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), which manages Hubble observations, some astronomers suggest images could be taken of nearby objects.

RELATED: Hubble at 25: Brief History of the Hubble Space Telescope

"You could see Saturn's rings sticking out of the page, Mars looking like a globe, or Jupiter and its moons moving," Joel Green, a project scientist at STScI, told Seeker. "There's a few scientific reasons, too. You might want to look at how cloud structures change in 3D, or how an impact happens in 3D."

Another possibility, he added, would be looking at a star explosion (or supernova) and from the distance between the telescopes, finding out where the explosion is coming from and examining certain features of the explosion.

Other observatories are planned after Webb. One is the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), which would use Hubble-class hardware that has a wider field of view. Its specialty would be dark energy and exoplanets. Another is the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which would look at planets passing in front of the brightest stars in our sky. These likely would get going in the 2020s, if funding for the missions is fully approved.

But the next generation is still being worked out. NASA draws heavily from the National Science Foundation's Decadal Survey when planning its missions. Right now, proposals are being formulated to present to members of the next decadal survey, which will be released in 2020.

RELATED: For NASA's Hubble Successor, Failure Isn't an Option

This will be the battleground for where UV astronomy is determined for the near future. NASA is planning to do up to four mission concept studies to present for the 2020 Decadal Survey, including a mission called the Large Ultraviolet/Optical/Infrared Surveyor (LUVOIR). As the name implies, it's supposed to be capable of observing in several wavelengths.

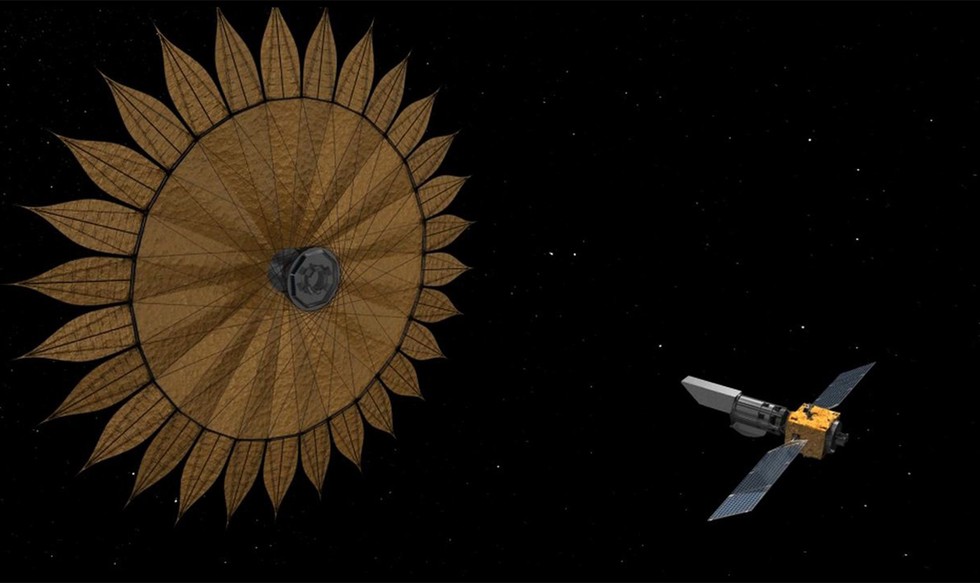

If it flies, it would examine protoplanetary disks, look for and image black holes, map the Milky Way and even look at nearby exoplanet atmospheres for signs of habitability. But it is competing against several other mission concepts, including one focused on infrared (Far-IR Surveyor), one for X-rays (X-ray surveyor) and a more modest UV and optical observer called HabEx. HabEx may use a special, separate shield to filter out a star's light for direct planet observations, which would be a first in astronomy.

"We're very hopeful that the national community in 2020 will fund one of these things and go forward," said Karl Stapelfeldt, the chief scientist of NASA's exoplanet science program. The aim is not only to be able to look at Earth-like planets around nearby stars, he said, but to study the rest of the universe as well.

There are other UV telescopes being proposed, such as Advanced Technology Large Aperture Space Telescope or ATLAST (which was considered in the last decadal survey) and the High Definition Space Telescope (HDST). This makes for a dizzying array of options and ideas for anybody trying to think ahead for the next generation of space telescopes.

While this is all being discussed, however, Webb is getting ready for launch. NASA's Rigby said she is greatly looking forward to the science that the telescope will provide.

"When you look the way Webb is designed, it is building on the legacy of Hubble," she said. "It's very much being built to do the things Hubble can't, because the things Hubble can do it's done so exquisitely... it's optimized in a totally different direction from Hubble, because Hubble has given us a legacy over 25 years within the range of its capabilities."

Originally published on Seeker.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.