Manned Orbiting Laboratory Declassified: Inside a US Military Space Station

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

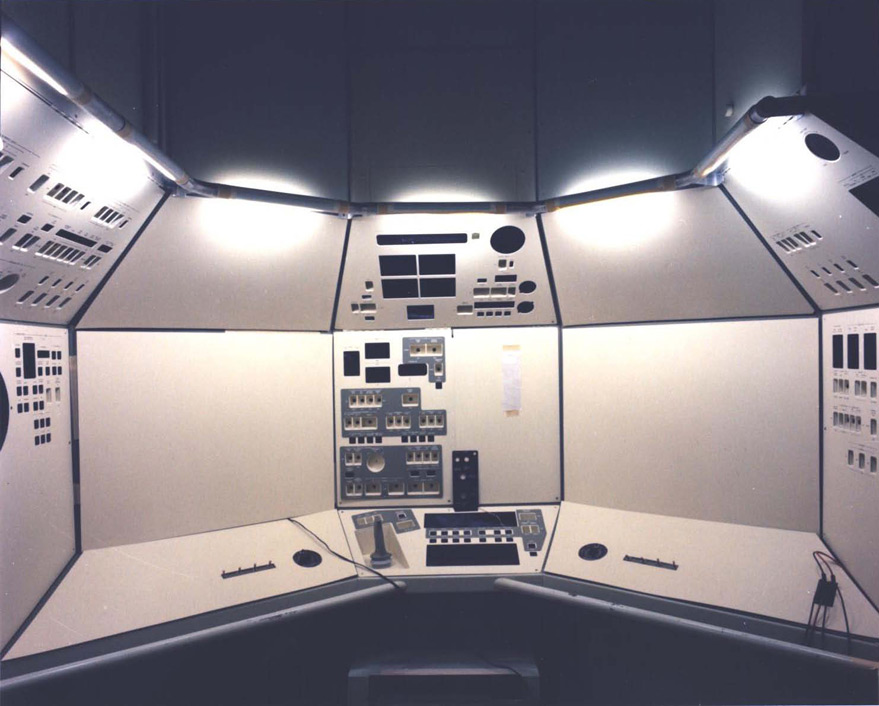

Control center

This may look like a spaceship set from a science fiction movie, but this image depicts a design mock-up for the controls inside the Manned Orbiting Laboratory.

A joystick controller can be seen at center, along with a console with buttons and screens for other data readouts.

Up next: Practicing for space

Practicing for space

Preparing the Manned Orbiting Laboratory for crewed missions meant practicing tasks in spacesuits like the scene shown here to see how well the station's design worked.

Up next: The human face

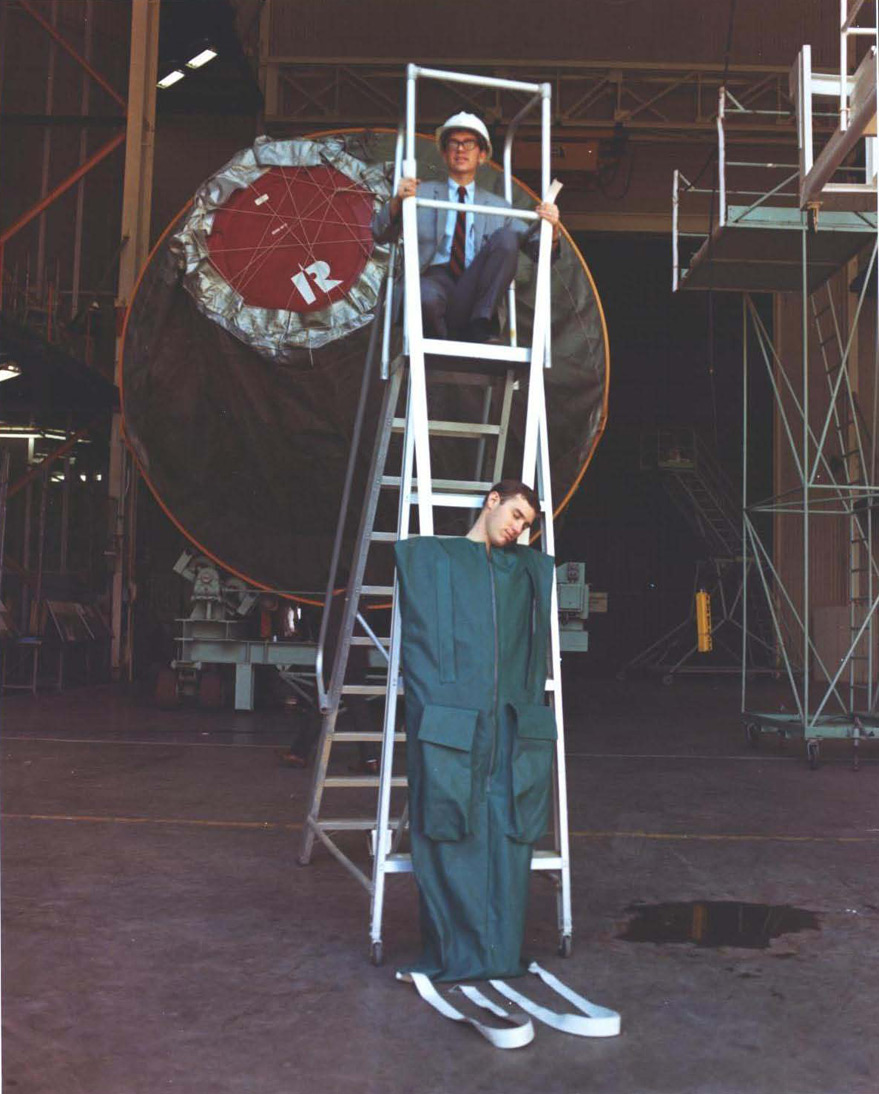

The human face

Pictured here is a person dressed as an astronaut, doing MOL testing. Just like NASA astronaut selections of the 1960s, the Manned Orbiting Laboratory astronauts were named publicly. Their faces were known and in a now-unclassified memo, a policy relating to MOL astronauts noted there was a slight (but real) risk that they could be captured by hostiles if they landed in the wrong spot.

While NASA astronauts worked for a civilian program, in the 1960s they were mainly recruited from the military branches for security and qualifications purposes. A similar policy was in place for the MOL, although in this case the astronauts had to be able to meet "top secret" requirements due to the clandestine nature of their mission. After MOL was cancelled, about half of the astronauts transferred to NASA. Among them was Bob Crippen, who eventually flew in the first space shuttle mission in 1981.

Up next: Living in space

Living in space

Life aboard the Manned Orbiting Laboratory would require more than just military reconnaissance in space. It would mean living in space as well. Here, an individual is seen inside a sleeping bag designed for astronaut use on the Manned Orbiting Laboratory. Unlike in this photo, no ladders would be necessary to climb into this sleeping bag on the MOL.

Up next: Walking the tightrope

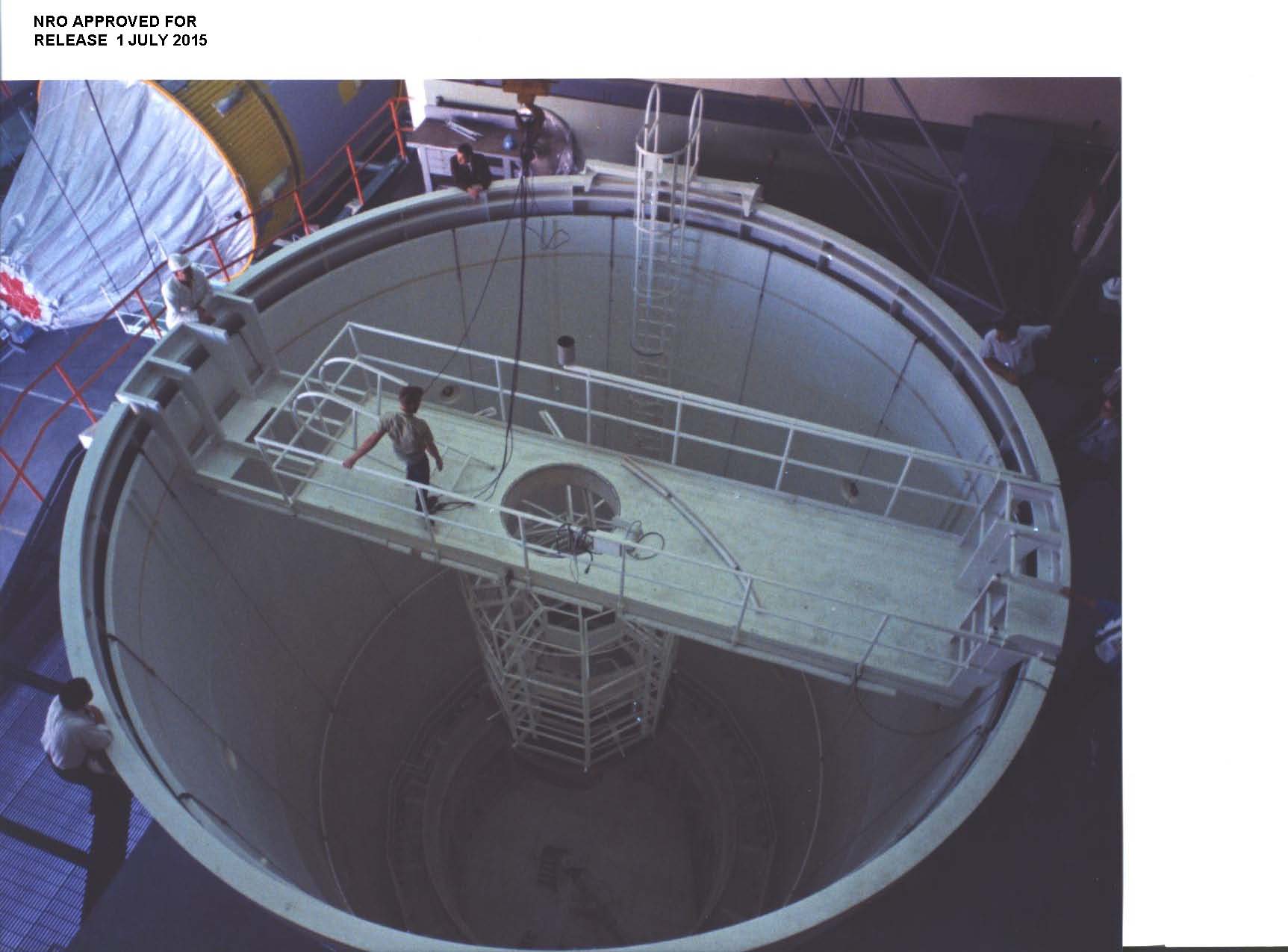

Walking the tightrope

The Manned Orbiting Laboratory never got to orbit, but it did get to assemble major components. In this picture, you can see a part of the massive hull that would have ridden into space behind the spacecraft. The astronauts would have had access to this area to perform experiments and do some of the main functions of the mission.

This was a similar design to the Skylab space station, which used a modified Saturn IV rocket stage to house the United States' first orbital laboratory. This allowed astronauts to stay in space, exercise and perform experiments for several weeks. The longest of the three crewed missions lasted 84 days.

Up next: Vast assembly

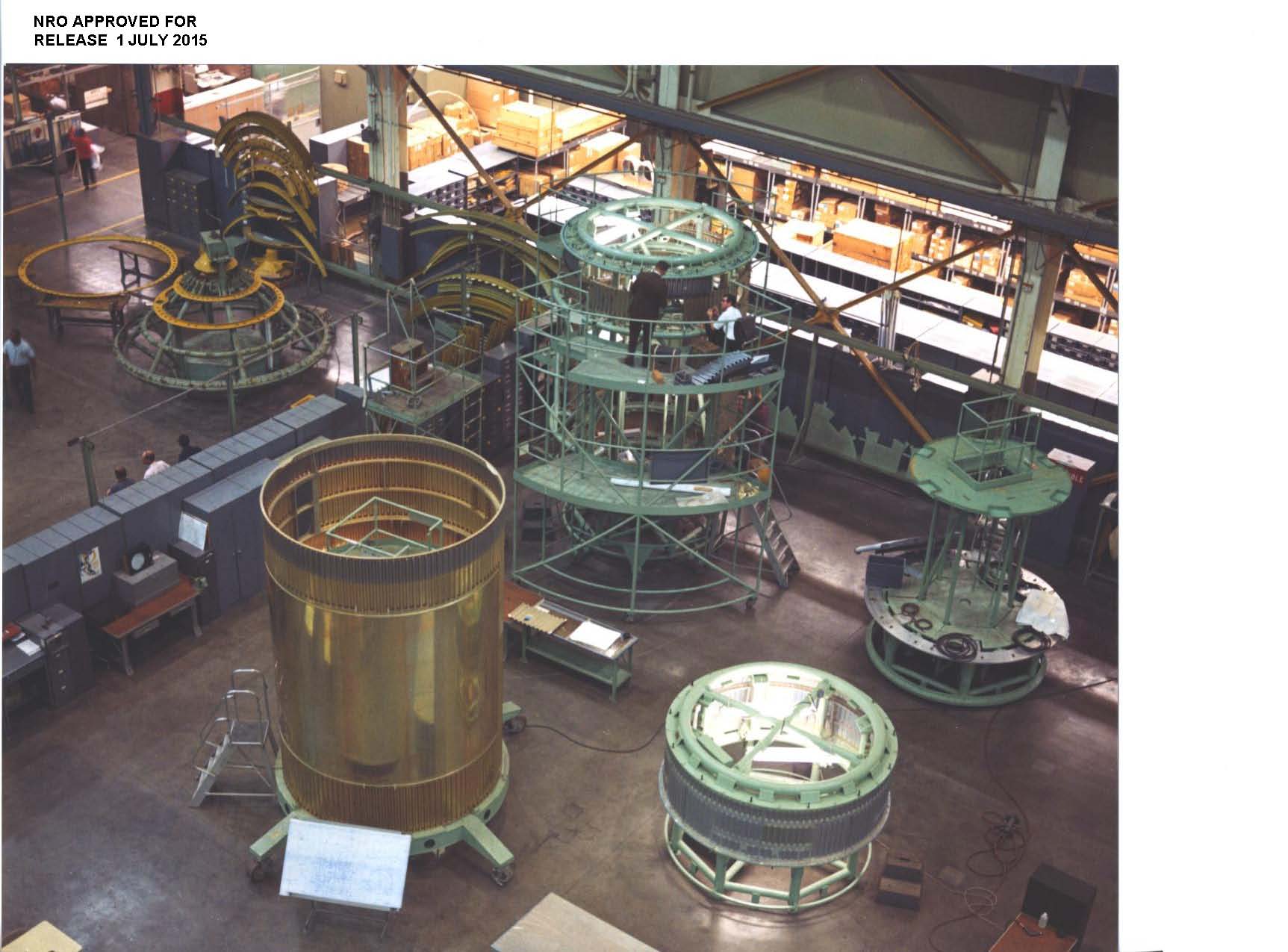

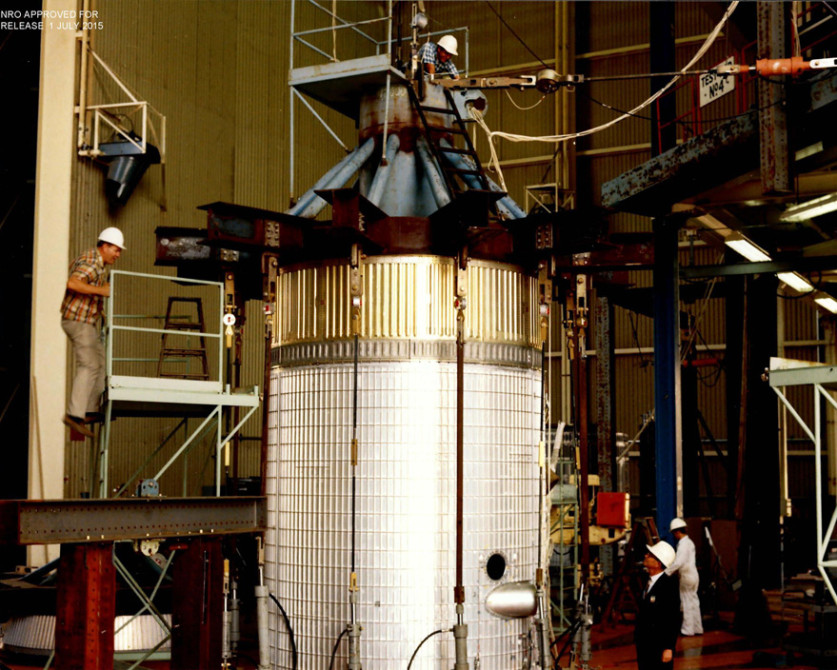

Vast assembly

To create a large spacecraft, you require large facilities. According to a 2014 Space Review article, the Manned Orbiting Laboratory was built in a large Huntington Beach, Calif. facility. After the program was cancelled in 1969, the people working at that facility naturally lost their jobs (which didn't help California's aerospace industry problems at the time).

The Space Review, which perused many of the MOL documents, adds that as of 2014, it was unclear what had happened to the unused hardware. How much of it was completed, and whether it was destroyed, remained open questions decades after MOL's cancellation.

Up next: Underwater work

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

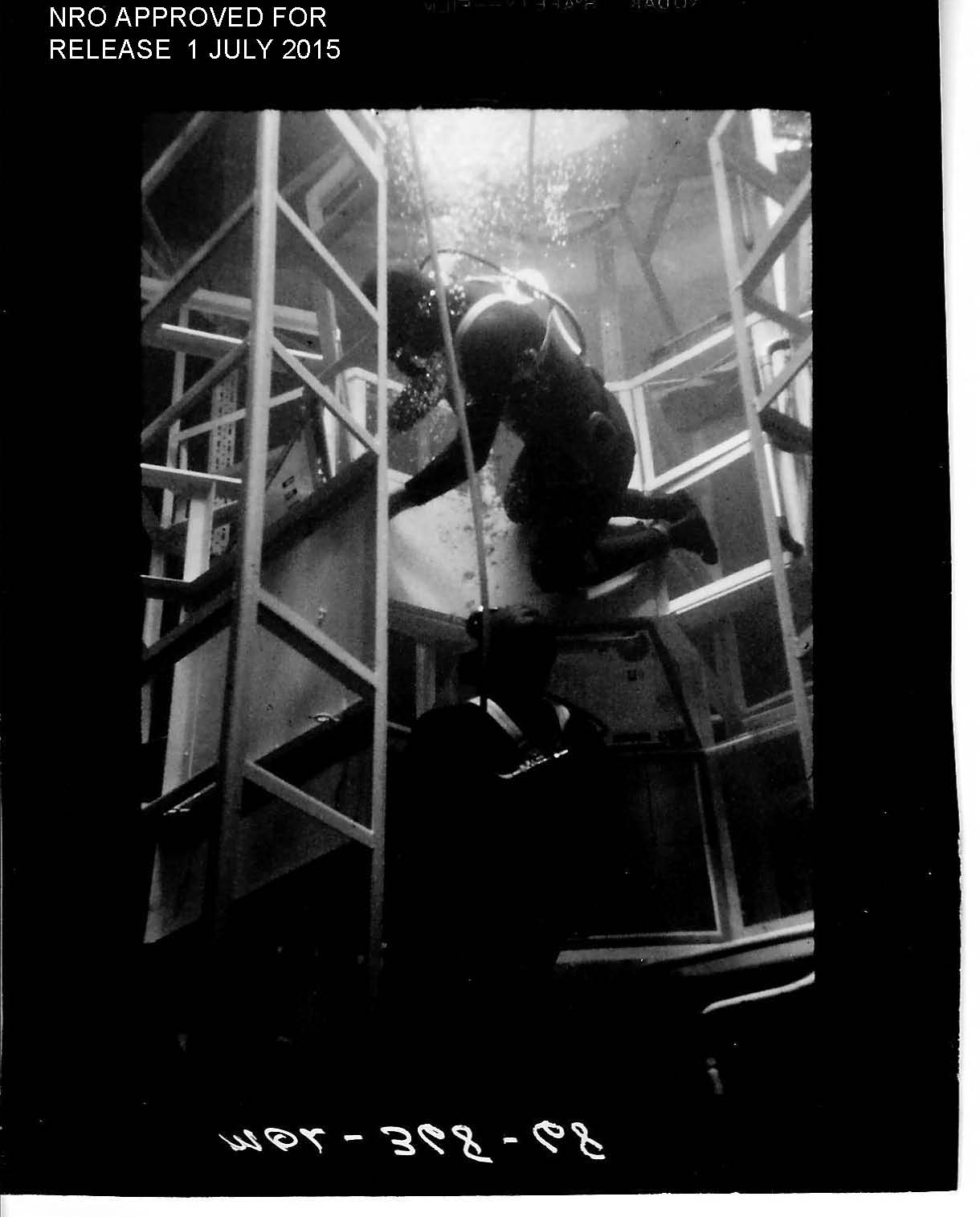

Underwater work

This picture shows a person in a scuba suit working underwater as part of Manned Orbiting Laboratory activities to prepare astronauts for spacewalks.

Spacewalks were an emerging skill for NASA and the Soviet Union in the 1960s. No one was very comfortable working in a “weightless” environment, and astronauts in the Gemini program reported many problems finding appropriate handholds and footholds on the spacecraft to get their work done.

Spacecraft tweaks were implemented. It wasn't until the end of the program, Gemini 12, that a spacewalk was able to complete all major objectives without exhausting the astronaut. [How NASA's Gemini Spacecraft Worked (Infographic)]

Up next: Space legacy

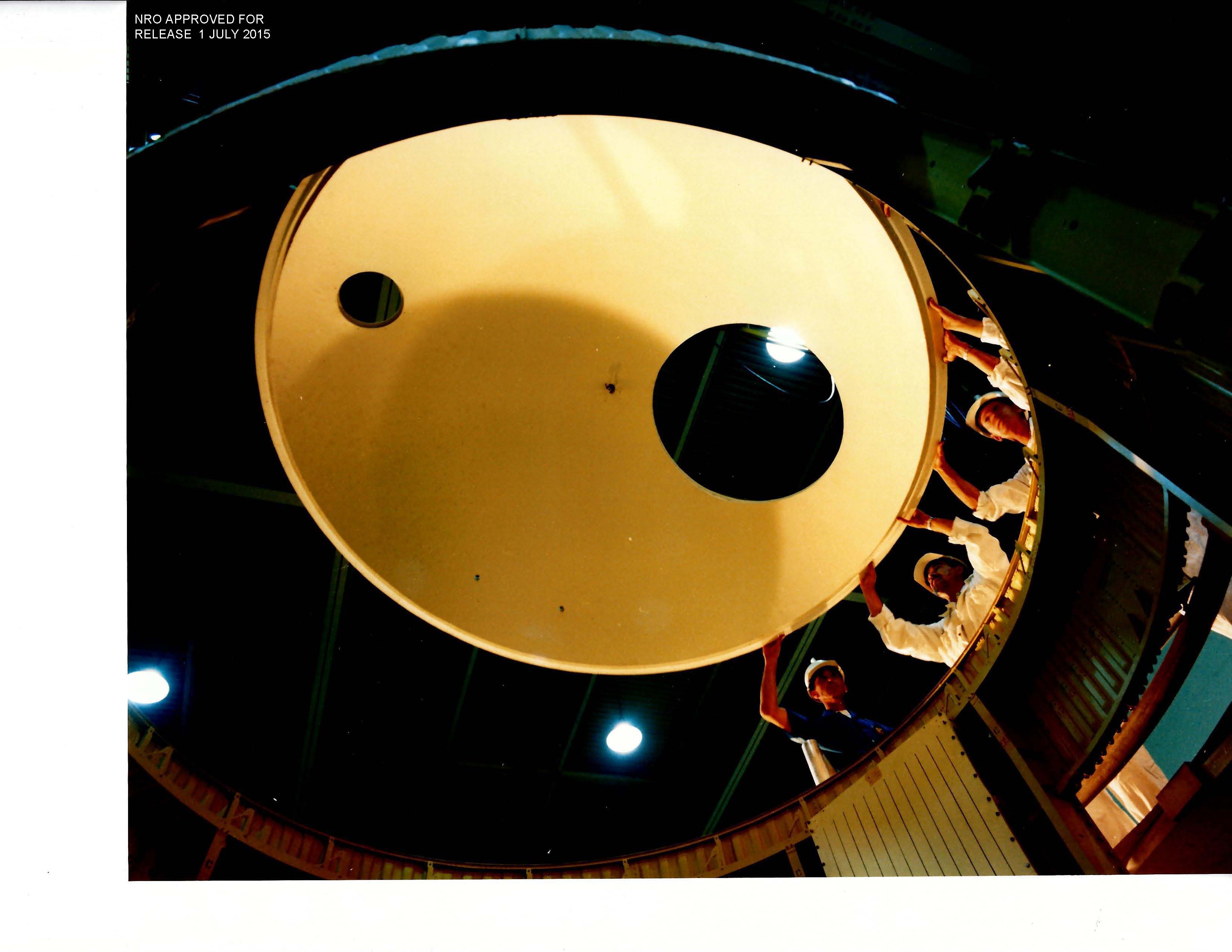

Space legacy

While space hardware (such as the pictured hardware) from the Manned Orbiting Laboratory never made it into orbit, the NRO noted in a PDF document that MOL did have a lasting legacy on space generally. While the astronauts had the most high-profile exit from MOL, personnel such as these ones were able to transfer to other security programs and use their knowledge from MOL, the NRO said.

The program also had certain spaceflight technologies that were recycled in other programs. For example, MOL astronauts had access to a more flexible spacesuit than Gemini astronauts because the MOL astronauts were required to move from the Gemini capsule to the lab once in orbit. This technology was transferred to NASA after MOL was concluded.

Up next: Modular construction

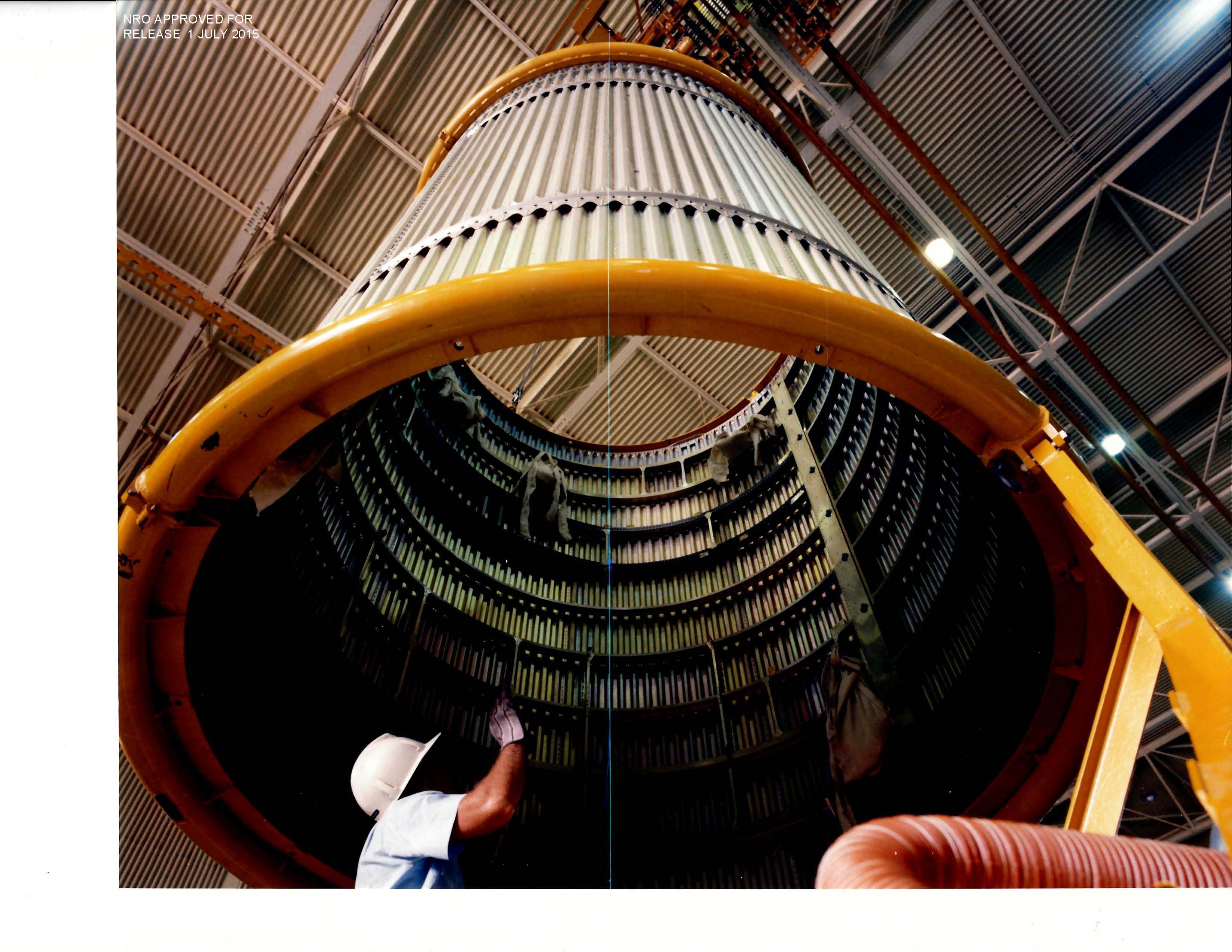

Modular construction

This picture shows a piece of the MOL being looked at by technicians. In the 1960s, spaceflight construction was an idea that you would see in diagrams – not something that was implemented for real. The International Space Station, however, saw many of its components assembled in orbit between the 1990s and the end of the space shuttle program in 2011.

This multi-module assembly was also a legacy of MOL, the NRO noted in the same PDF document. That's because MOL had proposals to launch more than one space module and then dock them together in orbit to create a larger structure. [Manned Orbiting Laboratory: Secrets of a US Military Space Station (Infographic)]

Up next: More releases to come

More releases to come

The 2015 document release of MOL, while heralded by the NRO, represents only a fraction of the information available on the program. The pictures shown in this slideshow – as well as more than 200 others – did not have captions attached to them. But the NRO said in the same PDF document that more information is coming soon.

“We anticipate releasing a new history of the MOL crew members in 2016. A CSNR [Center for the Study of National Reconnaissance] oral historian is preparing the history based on her interview of MOL crew members,” the NRO wrote.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.