What's It Like On Our Neighbor, Proxima b?

The newfound planet Proxima b is the closest planet outside our solar system ever discovered, and scientists think it might be amenable to life. But what would it be like to live on our nearest interstellar neighbor?

The two facts researchers are surest of are that it circles its star every 11.2 days — to match the telltale stellar wobble they used to identify the orbiting planet — and that its minimum mass is 1.3 times that of the Earth. The rest is up to probability and future measurements, but the results look promising — especially because of its 4.2 light-year distance from Earth at Proxima Centauri, the closest neighbor star to the sun.

"It's not only the closest terrestrial planet found, it's probably the closest planet outside our solar system that will ever be found because there's no star closer to our solar system than this one," Ansgar Reiners, an astrophysicist at Gottingen Institute for Astrophysics and co-author on the paper, said at a news briefing. Its closeness to Earth makes it not only a possible destination for humankind, but a perfect target to gather more information from home. [Proxima b: Complete Coverage of the Exoplanet Discovery]

Researchers think the planet is likely rocky, and it has a surface one could walk on — it's probably not a tiny gas planet. (Its location around a red dwarf star suggests it's not a giant gas planet, either, like Jupiter or Saturn.)

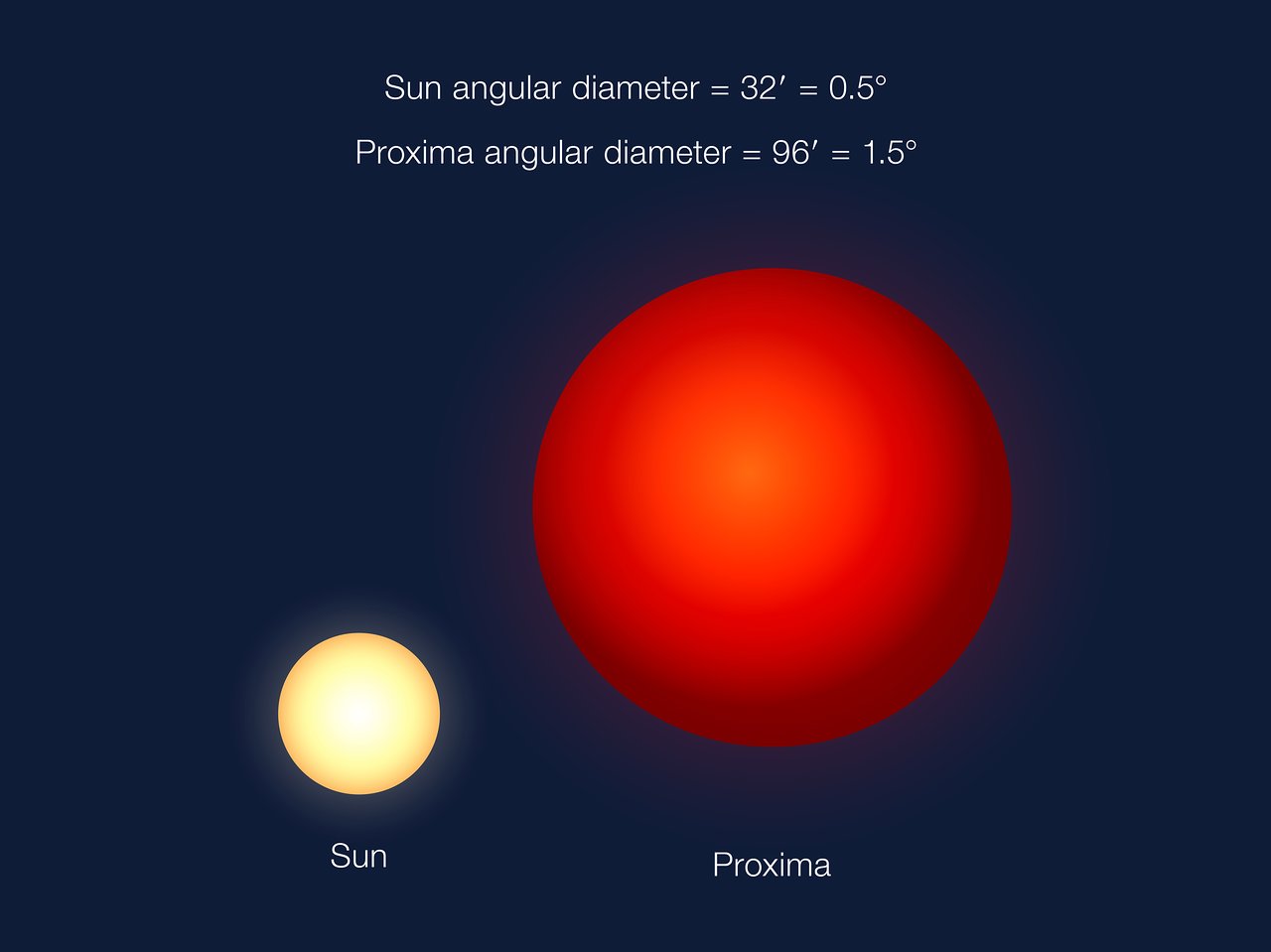

Its star, Proxima Centauri, is much fainter than the sun and just 0.12 times its mass, and the planet huddles nearby, at just 5 percent the distance between the sun and the Earth. (The star has a diameter just 1.4 times that of Jupiter.) Researchers think because of its close orbit the planet is likely tidally locked and in synchronous rotation, which means that it always presents the same face to its star as it orbits around (like Earth's moon does). One half of the planet is always bathed in the sun's radiation, and the other faces outward.

"One side is always sunny, the other is gloomy and dark," Guillem Anglada-Escudé, a researcher at Queen Mary University of London and lead author on the new paper, said during the briefing.

Looking up at the sky from the right location on Proxima b, then, one might see two bright dots of the nearby binary system, Alpha Centauri — a pair that researchers think are part of the same system as Proxima Centauri, even though it's relatively far away compared with the two stars' closeness.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Without an atmosphere, the planet's surface could hover at around minus 40 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 40 degrees Celsius). But that's no cause for alarm, the researchers said during the briefing — Earth itself would hover at around minus 4 F (minus 20 C) without an atmosphere. If this planet has an atmosphere, too, it could range from minus 22 to 86 F (minus 30 to 30 C) on its dark and light sides, making it warm enough to host liquid water on its surface.

Whether it has that atmosphere and water, though, depends a lot on the planet's history.

"It strictly depends on the initial conditions," Anglada-Escudé said. "Either this planet's dry, or it formed very far away and brought a lot of water from beyond the ice line [far away in the star's system, where comets and debris are icy rather than just rocky], or maybe started dry but comets rain every once in a while on the planet and make it water again."

"This is open for speculation, but chances are good — there are viable models and stories that lead to a viable, Earth-like planet today," he added.

Another thing to consider is the radiation beaming off the nearby star, researchers said — because Proxima Centauri is so close, strong enough X-ray and ultraviolet radiation would stand a chance of boiling off the water and stripping the planet's atmosphere. While the current high-energy radiation — about 100 times that of modern-day Earth, the researchers estimated — isn't enough to have that effect or to preclude life, it's possible that earlier in the star's lifetime it could have been violent enough to take a toll.

"None of this does exclude the existence of an atmosphere or of water," Reiners said. "It all depends on the formation of the system."

As for the modern-day radiation, "we don't think it's a showstopper here," Anglada-Escudé said. [Proxima b By the Numbers]

The researchers also mentioned other signals in the star's wobbles whose source was unsure — it may just be the star itself, or it might indicate another planetary neighbor, or one large planet with an entourage of smaller ones around it, the researchers said in a second press conference. That planet, though, would be farther out, larger and well away from the zone where liquid water can exist.

Further observations will help resolve whether or not it's a stellar system of one — and more information about what the planet and its system are like are surely coming soon, the researchers said.

"The good news is that it's so close," Reiners said. "This is not only nice for having it in our neighborhood, but this is also a dream for astronomers if we think about follow-up observations."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.