Supernova Ashes Found in Fossils Hint at Extinction Event

Supernova ash has been discovered in fossils that were created by bacteria on Earth, a new study finds.

Because the fossils contain a variety of iron that is most likely the product of a supernova event that occurred light-years from Earth, this finding also suggests that the event might have played a role in an extinction event on Earth, researchers said.

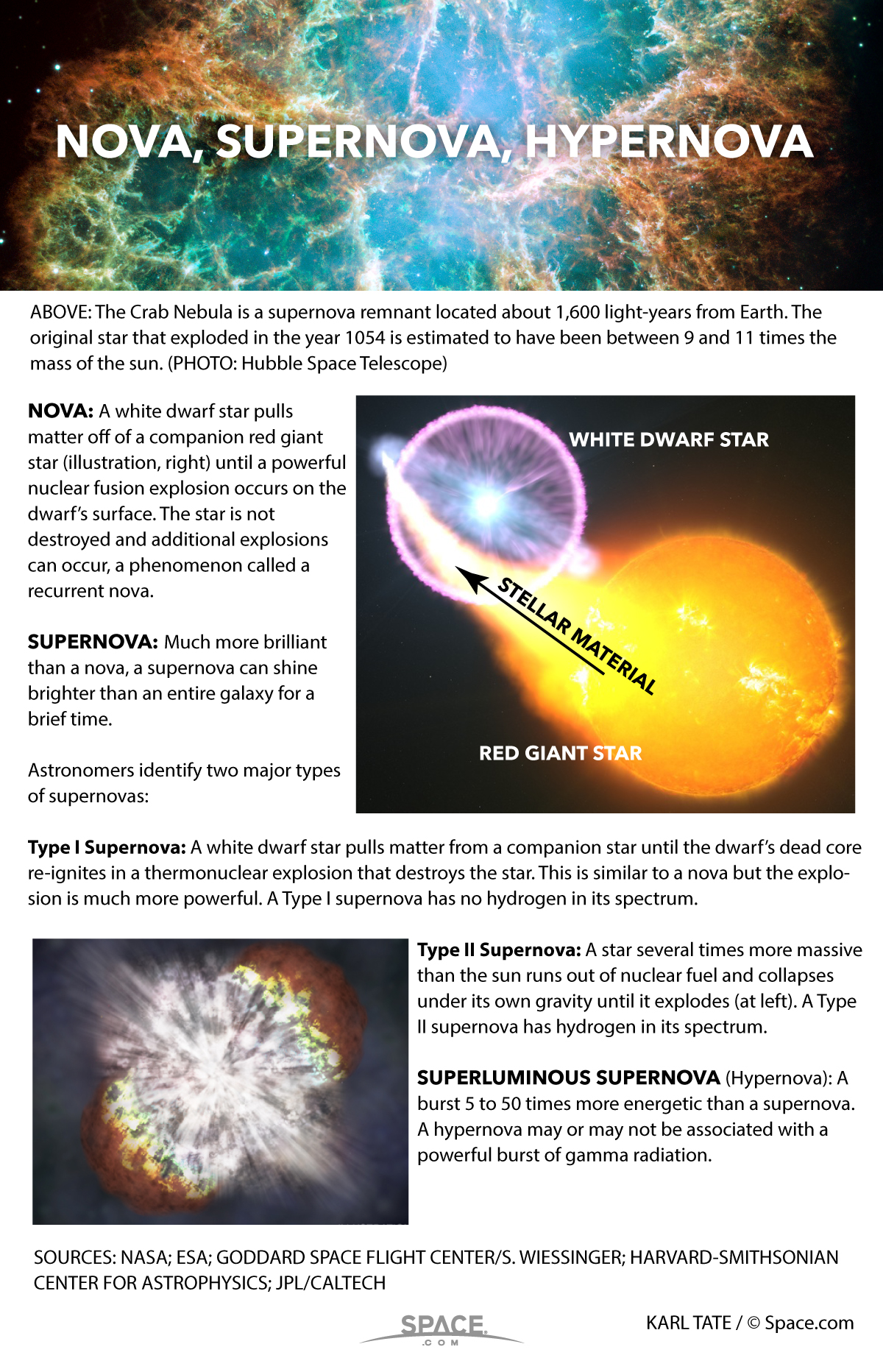

Supernovas are powerful explosions of giant, dying stars. These outbursts are visible all the way to the farthest corners of the universe, and are bright enough to briefly outshine all of the other stars in their host galaxies. [Amazing Supernova Images from Star Explosions]

Previous research has found that supernovas generate a mildly radioactive variety of iron known as iron-60. These cataclysmic explosions then hurl vast amounts of iron-60 — more than five to 10 times the mass of the sun — out into space. Iron-60 that's produced in other natural ways creates only up to one-tenth as much. As such, iron-60 that is found on Earth and on the moon likely is ash from supernovas.

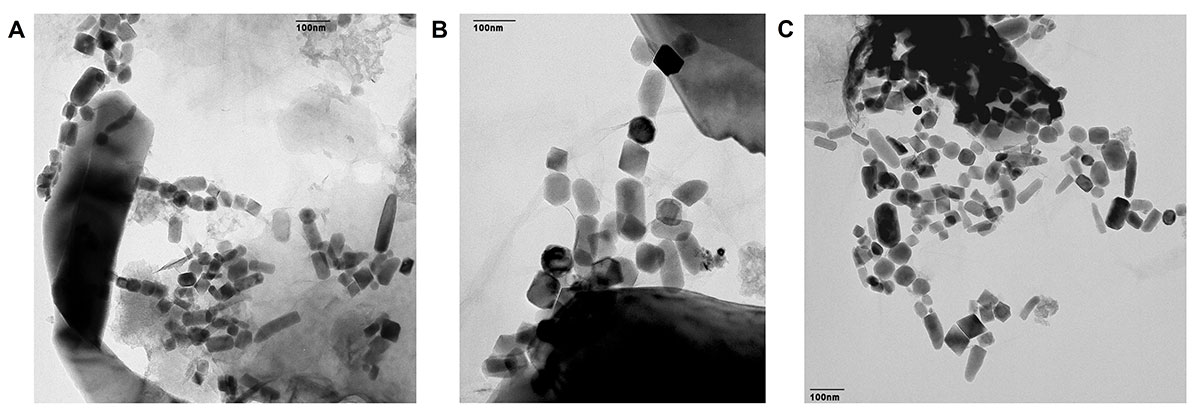

Now scientists have discovered iron-60 within fossilized chains of magnetic crystals of a mineral known as magnetite. These "magnetofossils," each of which is about 90 nanometers — or billionths of a meter — large, were created by microbes known as magnetotactic bacteria.

Previous studies have suggested that a supernova at least 325 light-years from Earth blasted the planet with iron ash about 2 million years ago. To look for traces of this debris, the researchers analyzed core samples of marine sediment that were extracted from the Pacific Ocean that dated from this span of time.

The scientists discovered that the magnetofossils that contained iron-60 first appeared in the core samples between 2.6 million and 2.8 million years ago. The supernova debris apparently then rained down on Earth for about 800,000 years, with iron-60 levels peaking about 2.2 million years ago.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Finding still-live atoms of iron-60 ejected from the guts of a supernova 2.6 million years ago within magnetofossils is awesome," said study co-author Shawn Bishop, an experimental nuclear astrophysicist at the Technical University of Munich in Germany. "Being able to detect them with the fantastic sensitivity we have — if you give me one atom of iron-60 in 10^16 [10 million billion] stable atoms of iron, we can find it — is awe-inspiring."

The researchers noted that this supernova debris rained down on Earth at about the same time as an extinction event that claimed mollusks such as marine snails and bivalves. A period of global cooling happened during that time as well.

"We can't say anything about the causative contribution of this supernova to this extinction, but — pun intended — it seems like an astronomical coincidence," Bishop told Space.com.

Future research can unearth evidence to support or refute this potential link between supernovas and extinctions, Bishop said.

The scientists detailed their findings online Aug. 10 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original story on Space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us