How to Form Io's Mountains? Just Squeeze!

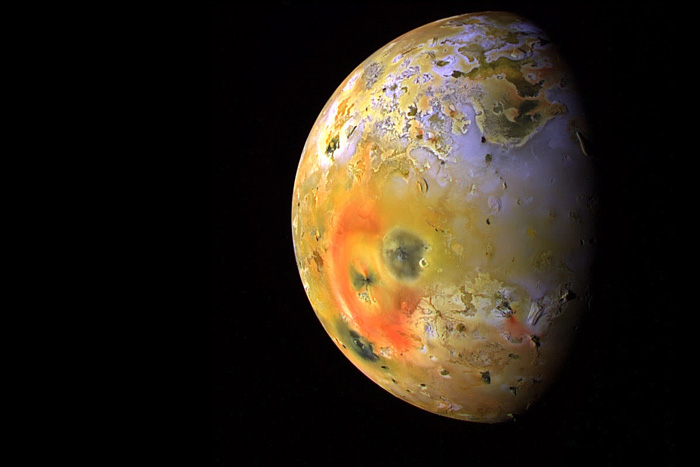

Jupiter's volcanic moon Io is full of mysteries, including how its mountains were formed. They have puzzled scientists for decades because they look nothing like mountains on Earth.

At home, we see mountains grow in ranges that can stretch across thousands of miles. But on Io, the more than 100 cataloged mountains mostly grow in isolation. What mysterious tectonic forces are at play here?

PHOTOS: Fire and Ice: Tides Drive Jupiter's Ocean Moons

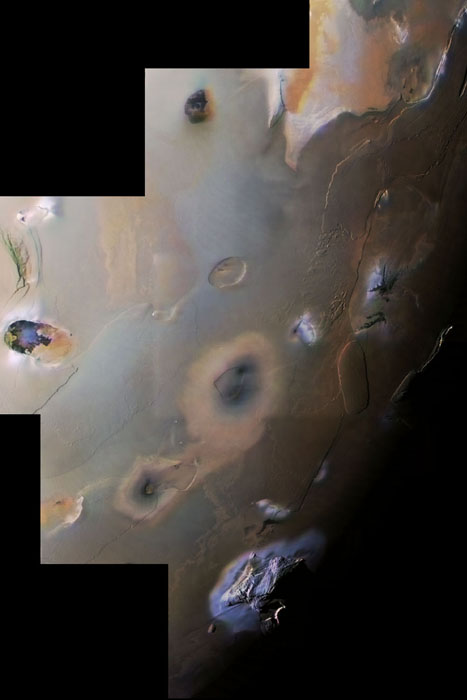

Io is so active that it's hard to look at the tectonics from space; molten lava coats the surface at an incredible rate of five inches per decade. So to answer the question, a new study used simulations to figure things out.

"The planetary community has thought for a while that Io's mountains might be a function of the fact that it is continuously erupting lava over the entire sphere," lead author William McKinnon, a planetary scientist at Washington University in St. Louis, said in a statement. He co-wrote a paper about this in 2001.

ANALYSIS: Icy Europa Does Battle With Solar System's Most Hellish Moon

"All that lava spewed on the surfaces pushes downward and, as it descends, there's a space problem because Io is a sphere, so you end up with compressive forces that increase with depth."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

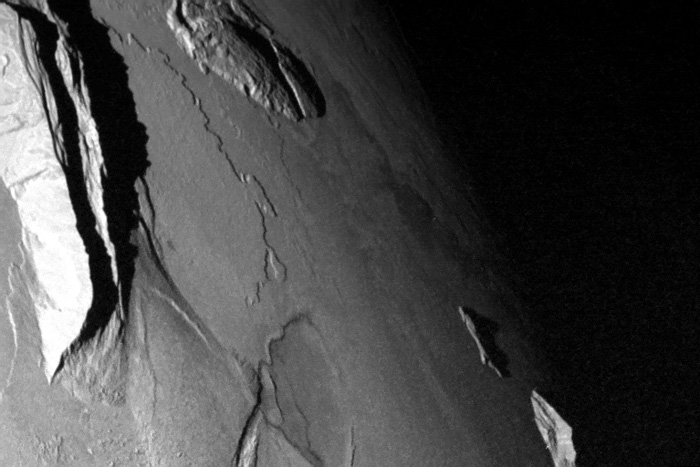

The new work simulates this hypothesis, but focuses on the fact that Io's compression gets stronger as you go deeper into the moon. This creates strain in a single fracture created deep inside of Io and then erupting to the surface, creating a cliff. The scientists also suggest this could explain why so many recent eruptions are found near the mountains.

"The compressive forces deep in the crust are incredibly high," McKinnon said. "When these faults breach the surface, those forces are released, and the entire stress environment around the fault changes, providing a pathway for magma to erupt."

NEWS: Volcanoes on Jupiter's Moon Io Are All Wrong

The simulations also may show why Io has some mountains that split over time. That's because the lava inside the crust creates both compression and high temperature. Heating rocks causes them to split because they have nowhere to expand to. This is especially prevalent when the volcano is not erupting and carrying away the lava, reducing the pressure.

The work was published in Nature Geoscience.

Originally published on Discovery News.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.