Some Science Coming from Japan's Ailing Hitomi Satellite

SALT LAKE CITY — Japan's troubled Hitomi satellite managed to collect some science data before going silent last month, scientists said.

Officials haven't heard from the Hitomi X-ray astronomy satellite since late March, about six weeks after the satellite's launch, and the craft appears to have broken into several pieces. But Hitomi did manage to complete two scientific measurements before the trouble hit, said Ann Hornschemeier, a scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

"I am aware of the situation right now with Hitomi," Hornschemeier said here Sunday (April 17), during a session at the American Physical Society's April Meeting. "However, it did gather science data. There are science-data activities going on right now. At NASA, we're still carrying it as an operating mission."

Ralph Kraft, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Massachusetts, also spoke briefly about the Hitomi results during his presentation in the same session, which focused on NASA's Physics of the Cosmos program.

"Hitomi actually made two observations, science-calibration observations," Kraft said. "One was of the Crab Nebula; one was of the Perseus cluster."

Kraft clarified that Hitomi managed to take spectroscopic data of these two objects. Spectroscopy allows scientists to study the chemical and atomic properties of a source, based on the light that the source emits.

Kraft is not working on the Hitomi science analysis himself. However, he said he has seen preliminary results from that analysis, which he said are not yet public. Kraft indicated that the results had been submitted for publication.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

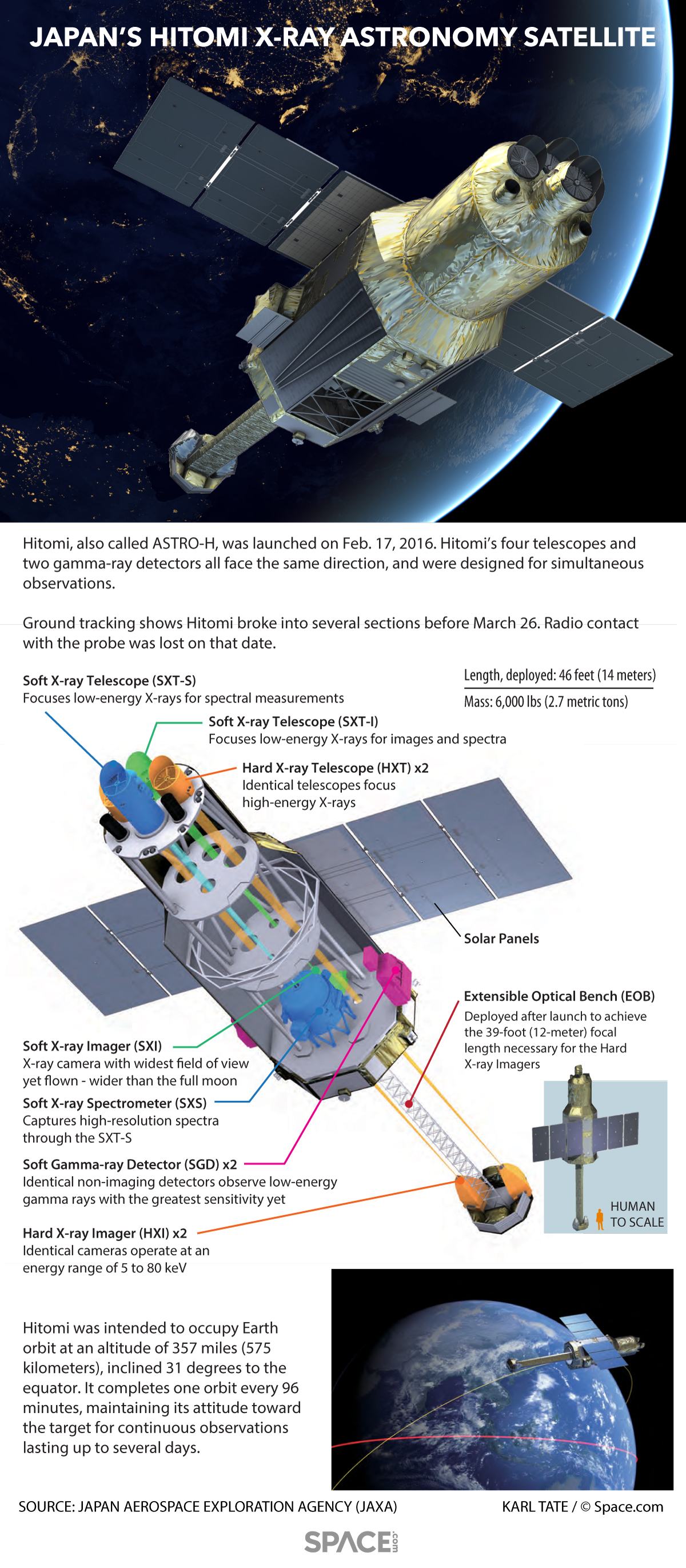

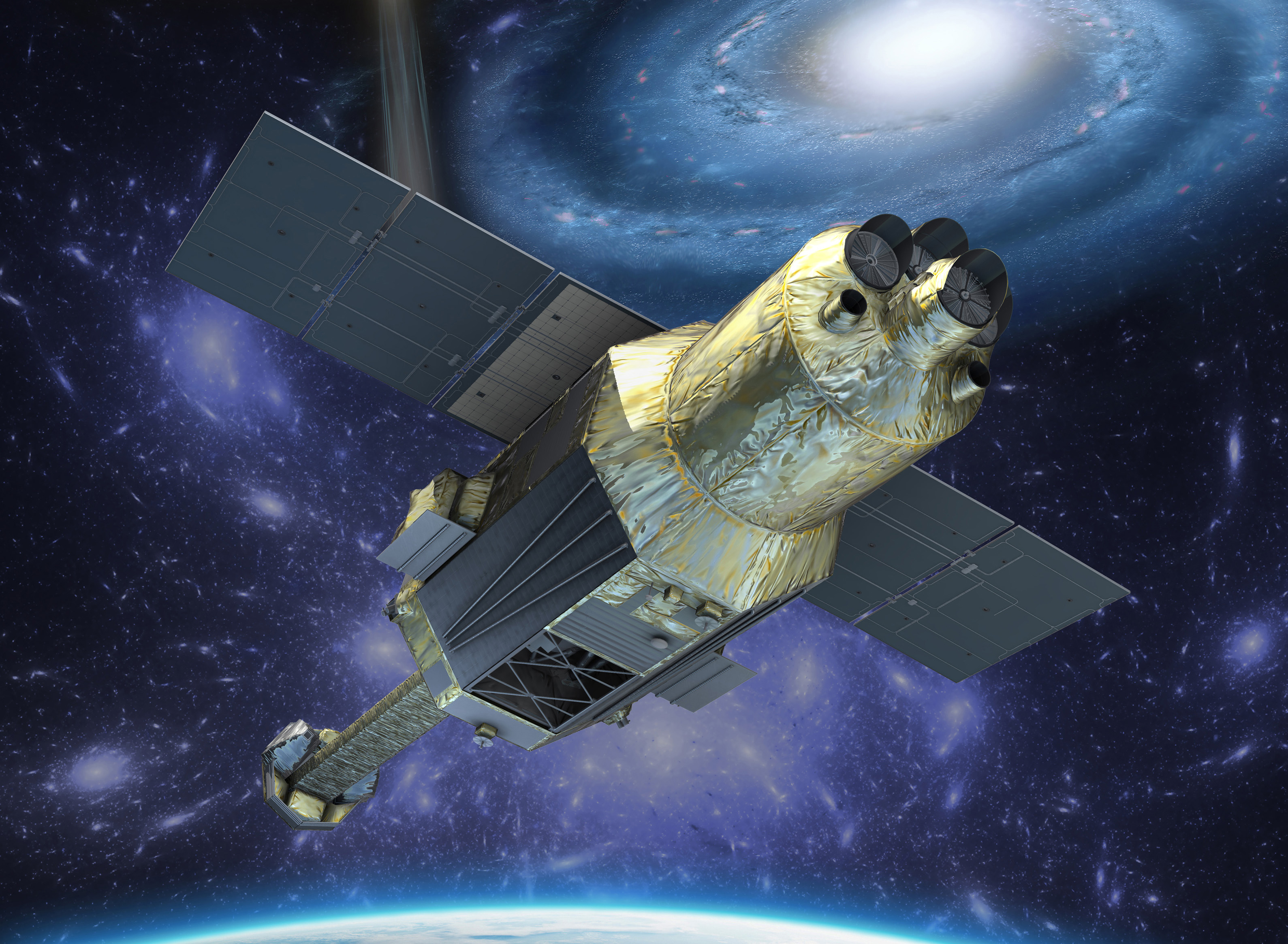

Hitomi, also known as ASTRO-H, launched to Earth orbit on Feb. 17. The satellite is equipped with instruments to observe the sky in both X-ray and gamma-ray wavelengths; its planned observations were intended to help scientists study dark matter distribution in the universe, the evolution and large-scale structure of the universe, black holes and other extreme states of matter, and many other phenomena.

It's unclear what exactly happened to Hitomi. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) said it hasn't given up hope on saving the satellite, but the long silence and the apparent breakup of the probe are obviously not good news.

"This is a real tragedy for our community that Hitomi is having problems," Kraft said.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter