'Frozen Lake' on Pluto May Point to a Warmer Time

NASA's New Horizons spacecraft has spotted evidence that liquids might have once flowed across the dwarf planet that stole everyone's heart.

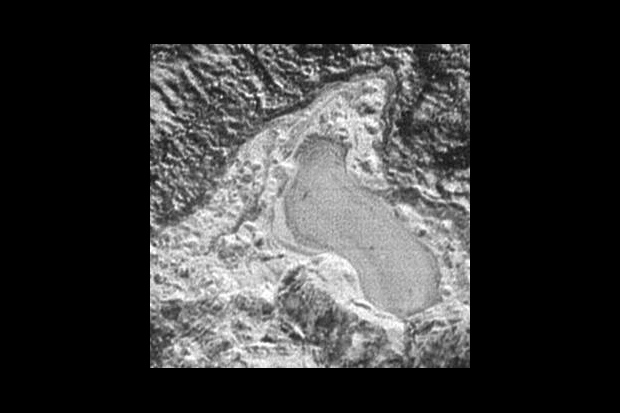

The evidence comes in the form of a frozen lake that researchers think once harbored liquid nitrogen. At its widest point, the lake appears to be about 20 miles (30 kilometers) across. New Horizons spotted the lake during its July flyby of the dwarf planet, which also gave observers the iconic view of the broad, heart-shaped region on Pluto's surface that is nicknamed Tombaugh Regio.

"In addition to this possible former lake, we also see evidence of channels that may also have carried liquids in Pluto's past," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said in a statement.

Although the dwarf planet orbits the sun at an icy distance, a higher pressure in Pluto's atmosphere sometime in the past would have caused warmer conditions on the surface. Today, Pluto's atmosphere has a pressure that's 1/100,000th of that found at sea level on Earth. But in the past, its atmospheric pressure may have been as much as 10,000 times higher — 40 times as high as the atmospheric pressure found on Mars today.

Such high pressure would have led to a hot environment that allowed liquid nitrogen to flow on the planet's surface.

So what has caused Pluto to lose its atmospheric pressure? Scientists think the dwarf planet's changing seasons (which shift much more radically than they do on Earth) could cause the atmosphere to wax and wane. Earth is tilted at an angle of 23 degrees on its axis, which keeps the Arctic and Antarctic regions confined, but Pluto's tilt wavers at about 120 degrees, which causes drastic changes in Pluto's climate over the course of millions of years.

Had New Horizon's flyby taken place a few millions years ago, the tiny planet would have looked vastly different than it does today. Nitrogen would have rained in the highlands, flown down into the plains and even collected as liquid in a lake. Today, all that remains is the stark outline of its frozen ghost.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Follow Shannon Hall on Twitter @ShannonWHall. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com

Shannon Hall is an award-winning freelance science journalist, who specializes in writing about astronomy, geology and the environment. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scientific American, National Geographic, Nature, Quanta and elsewhere. A constant nomad, she has lived in a Buddhist temple in Thailand, slept under the stars in the Sahara and reported several stories aboard an icebreaker near the North Pole.