Rare Event: Mercury to Cross the Sun Nov. 8

In November, the planet Mercury will make a rather feeble attempt to eclipse the Sun.

On Nov. 8, Mercury will pass through inferior conjunction, a point in its orbit where it is directly between Earth and the Sun. Normally the innermost planet is not visible during an inferior conjunction.

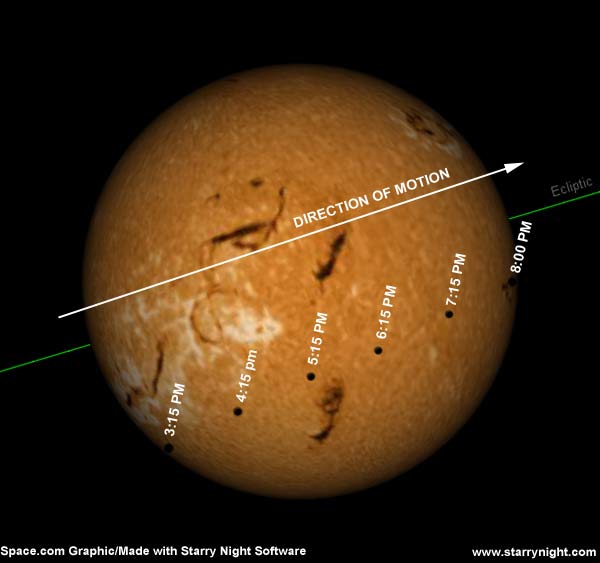

But this time the setup will produce a striking celestial phenomenon that can be viewed with small telescopes when Mercury's tiny silhouette slowly crosses in front of the solar disk [image]. Astronomers refer to such an event as a "transit."

Care must be taken to view the event with proper filters to avoid eye damage.

Rare event

A transit is a relatively rare occurrence. As seen from Earth, only transits of Mercury and Venus are possible. This is the second of 14 transits of Mercury that will occur during the 21st century.

| Safe Viewing Never look directly at the Sun with your naked eye or through a telescope or binoculars. Severe eye damage can result. | Safe Viewing | Never look directly at the Sun with your naked eye or through a telescope or binoculars. Severe eye damage can result. |

| Safe Viewing | ||

| Never look directly at the Sun with your naked eye or through a telescope or binoculars. Severe eye damage can result. |

With proper viewing filters, the transit will be visible with small telescopes. Viewers should use special, approved filters that can be purchased from reputable dealers of astronomy products.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Sun's image and the shadow of Mercury can also be projected through a telescope onto a white screen, sheet of paper or wall.

The entire transit from start to finish will be visible in its entirety only from the west coast of North America, (including central and southern Alaska), Hawaii, New Zealand and the east coast of Australia. From Australia and New Zealand the transit will occur on the morning of Nov. 9.

From the United States, those situated to the east of a line running from roughly northern Idaho to westernmost Texas will be able to see the beginning stages of the transit, but sunset will intervene before Mercury can move off the Sun's disk [map].

What to expect

The tiny disk of Mercury will begin moving on to the Sun at 2:12 p.m. EST (11:12 a.m. PST) and will take about 2 minutes to move completely onto the Sun's disk. The planet will be recognizable along the lower left edge of the Sun as a tiny, black, sharp-edged dot, but having only 1/194 the Sun's diameter.

Just under five hours later, Mercury will reach the Sun's right (west) edge. Mercury will take about 2 minutes to move completely off the disk of the Sun, beginning at 4:08 p.m. PST.

In those eastern regions where the Sun will set before the transit ends, a good observing site should have a low horizon to the south of due west. It is a good precaution to check the Sun's setting point a day or two beforehand, to verify that trees or buildings do not block the view.

Safe equipment needed

Unlike a transit of Venus, a transit of Mercury is not visible with the unaided eye. A telescope must be used, magnifying at least 30-power to bring out the "dark dot" of Mercury in silhouette against the Sun's disk.

Eye safety is always a prime concern when dealing with the Sun. Never look directly at the Sun through a telescope! Rather, you should project the enlarged solar image onto a white card or screen or use proper, approved solar filters.

SPACE.com will provide more observing details and information about the transit on Nov. 3.

- Images: 2003 Mercury Transit

- More About Transits

- Images: 2004 Venus Transit

- Sky Calendar & Moon Phases

- 10 Steps to Rewarding Stargazing

- Astrophotography 101

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for The New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.