Bursting the Spherical Bubble: Universe Might Be Pill-Shaped

Instead of being perfectly round like a globe, the universe might be a bit stretched in shape like a pill.

The newly proposed shape could be caused by a magnetic field that pervades the entire cosmos or defects in the fabric of space and time, researchers said.

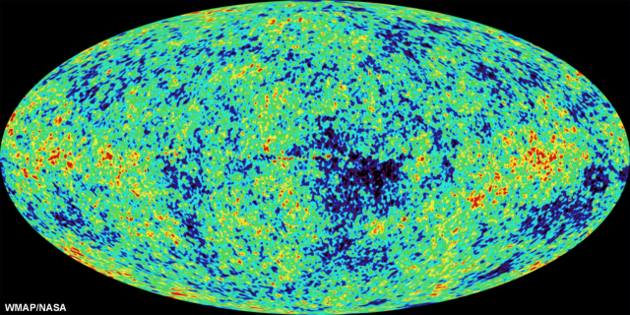

Scientists in Italy base their proposal off data gathered by a NASA satellite known as the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP). This spacecraft is designed to scan the sky and measure the temperature of the heat left over from the Big Bang and now present throughout the universe in the form of microwaves.

So far data from this probe has helped nail down some of the most important details about the universe. This includes the age of the universe since the Big Bang, at 13.7 billion years; the time when the first atoms formed, at 380,000 years after the Big Bang; and how much of the universe is made of either ordinary matter or the mysteries known as dark matter and dark energy, at roughly 5, 25 and 70 percent, respectively.

The quadrupole anomaly

The satellite also revealed an oddity concerning the way in which portions of the sky contribute to the overall map of cosmic microwaves. When it comes to the largest samples of the sky, the level of microwave radiation seems to be under-represented. On the other hand, smaller samples seem to be contributing radiation at expected levels.

Now astrophysicist Leonardo Campanelli of the University of Ferrara and his colleagues Paolo Cea and Luigi Tedesco at the University of Bari, all in Italy, have found that a universe shaped a bit like an oval can explain this so-called "quadrupole anomaly."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If the universe did not expand as a sphere after atoms first formed but instead as a slightly more elongated shape known as an ellipsoid, that would explain the odd cosmic microwave intensities seen at the largest scales, the researchers suggest. Some parts of a nonspherical universe would be farther away than others, and thus appear slightly fainter, a minute difference mostly imperceptible when only looking at tiny slices of the sky.

According to Campanelli and his colleagues, the universe may be roughly 1 percent more eccentric, or nonspherical, than previously often believed. An ellipsoid universe could be caused by a magnetic field pervading the cosmos that stretches space-time, he said, or by space-time defects such as cosmic strings, immensely dense structures just a proton or so wide stretched to intergalactic scales, whose gravity could distort space and time.

Bigger headache

While NASA astrophysicist Gary Hinshaw at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., felt it "fair to say that the data weakly favor the ellipsoidal model," he told SPACE.com that invoking an ellipsoid shape for the universe to solve the quadrupole anomaly created a bigger headache involving why the universe might be ellipsoid to begin with.

"It is actually difficult to understand how an ellipsoidal model would arise 'naturally' in cosmology, so the burden switches from explaining a very mild 'anomaly' to explaining a fundamentally new feature of our universe," Hinshaw said.

The scientists reported their findings in the Sept. 29 issue of the journal Physical Review Letters. Future space missions that better see how cosmic microwaves are polarized could test the ellipsoidal model.

This article is part of SPACE.com's weekly Mystery Monday series.

- The Strangest Things in Space

- Does the Universe Have an Edge?

- Understanding Dark Matter and Light Energy

- 10 Confounding Cosmic Questions

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us