Stellar Photo Reveals Cosmic Crashes Waiting to Happen

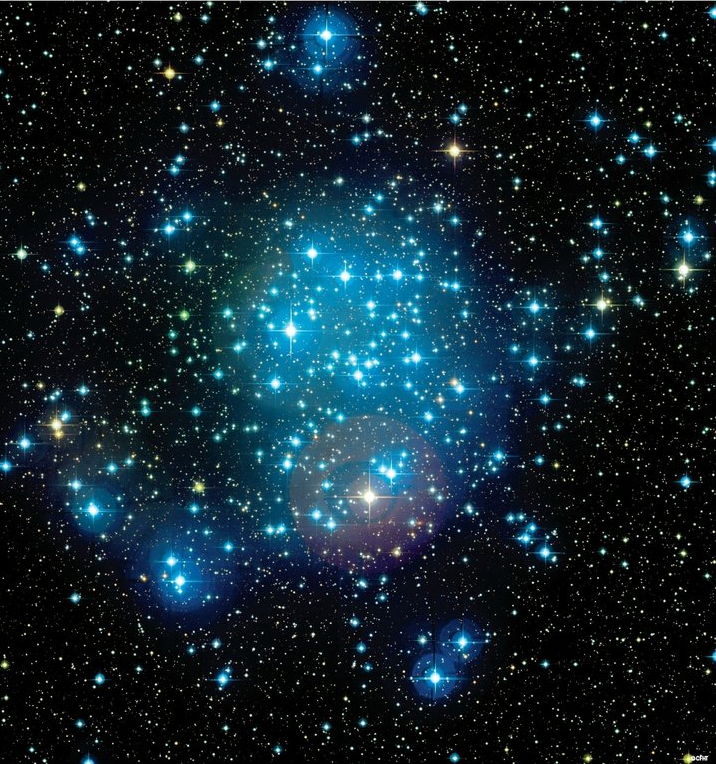

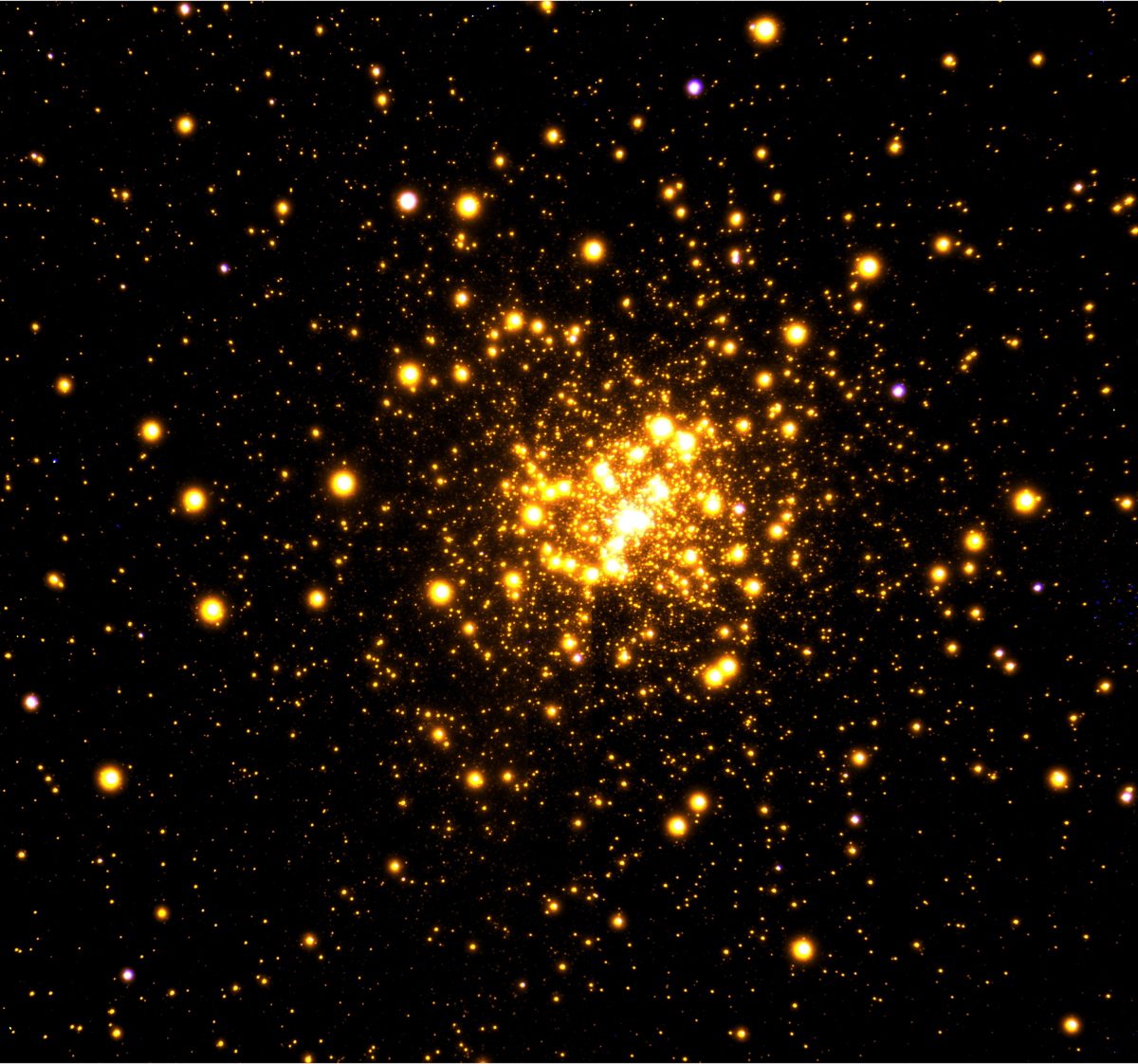

Densely packed clusters of stars are accidents waiting to happen in space. Case in point: This new photo shows a spot near the center of the Milky Way with a crowd of stars likely to collide, merge and push one another around.

The photo, captured by astronomers using a Gemini Observatory telescope in Chile, shows Liller 1 — a star cluster located about 26,000 light-years from Earth, behind a thick veil of dust. Astronomers were able to capture the ultraclear picture on the infrared and near-infrared spectrum using the observatory's Gemini South telescope.

The stars have an estimated mass of about 1.5 million suns and are packed so tightly that it's a recipe for cosmic crashes, scientists said. [Stunning Space Photos from the Gemini Observatory]

"Although our galaxy has upwards of 200 billion stars, there is so much vacancy between stars that there are very few places where suns actually collide," Douglas Geisler, of the University of Concepcion in Chile, principal investigator of the original observing proposal, said in a statement. "The congested, overcrowded central regions of globular clusters are one of these places. Our observations confirmed that, among globular clusters, Liller 1 is one of the best environments in our galaxy for stellar collisions."

Gemini's adaptive optics system was the key to grabbing the image — it uses a moving mix of laser guides and deformable mirrors to adjust for the distorting impact of the atmosphere and capture a sharp image. Orbiting telescopes like Hubble don't have to compensate for the atmosphere's movement. However, the Hubble telescope, in particular, does not have access to the specific band of near-infrared light that pierces interstellar dust most clearly.

Study team member Francesco Ferraro, of the University of Bologna in Italy, described star collisions as a game of cosmic billiards — the smaller the table, and the more balls on it, the more likely collisions are to happen.

"Indeed, our observations confirm Liller 1 as one of the best 'laboratories' where the impact of star-cluster dynamics on stellar evolution can be studied," Ferraro said in the same statement.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The research was detailed in The Astrophysical Journal in June.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.