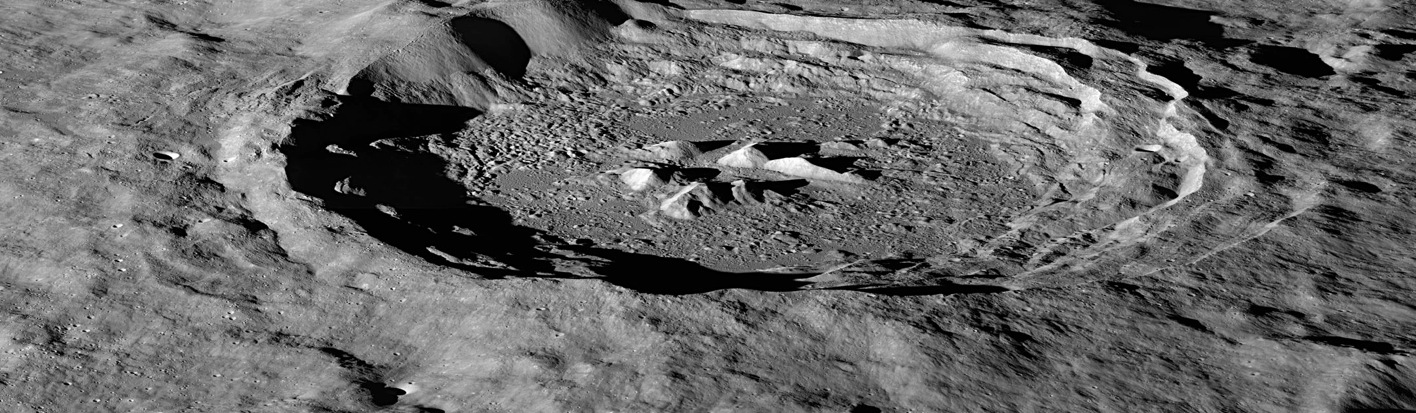

Moon Water Ingredient More Plentiful on Slopes Facing Lunar South Pole

Future moon colonists seeking water should focus on crater slopes that face the moon's south pole rather than those that face the equator, according to new data.

That conclusion comes after NASA's long-running Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) discovered there is very slightly more hydrogen — 23 parts per million by weight, on average — in "polar-facing slopes." Hydrogen could be a sign of lunar water since it, along with oxygen, form to make water. If this hypothesis is confirmed and there is enough water available, future colonists could mine the liquid rather than transporting it from Earth.

"Here in the Northern Hemisphere, if you go outside on a sunny day after a snowfall, you'll notice that there's more snow on north-facing slopes because they lose water at slower rates than the more sunlit south-facing slopes," lead author of the water study Timothy McClanahan said. "We think a similar phenomenon is happening with the volatiles on the moon." [Photos: The Search for Water on the Moon]

It's unclear how much hydrogen is available. Most polar-facing slopes are below the resolution of LRO's Lunar Exploration Neutron Detector (LEND) instrument that did the measurements. It is possible that hydrogen exists in areas that can't yet be spotted, but the water abundance found so far is tiny. "The amounts we are detecting are still drier than the driest desert on Earth," McClanahan of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland added.

Researchers also aren't sure if the hydrogen is a signal of water (two hydrogen atoms bound to an oxygen atom) or hydroxyl, which is made up of an oxygen and hydrogen molecule.

The hydrogen itself likely came from several different sources. Comets and asteroids could have spread water while impacting the lunar surface. Hydrogen is also abundant in the solar wind, a constant stream of particles from the sun that sometimes impact the moon. When the hydrogen hits the surface, it could mix with oxygen found in the silicate rocks there to create hydroxyl or water.

Before LRO arrived at the moon, researchers hypothesized that hydrogen could only survive in permanently shadowed craters protected from the sun's heat. Subsequent observations by the spacecraft have shown hydrogen is far more widespread.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team combined LEND observations with other data from LRO to come up with the hydrogen hypothesis, including topography and temperature maps. This allowed scientists to map the hydrogen abundance against the conditions on the surface.

Results based on the research were published in the journal Icarus. The team is also analyzing craters in the moon's northern hemisphere to see if a similar trend takes place there.

Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.