Quadruple Star Babies Found in Cosmic Womb

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

For the first time, a litter of four infant star siblings have been seen gestating in the belly of a gas cloud. Researchers say the finding supports the theory that most stars do not begin their lives alone.

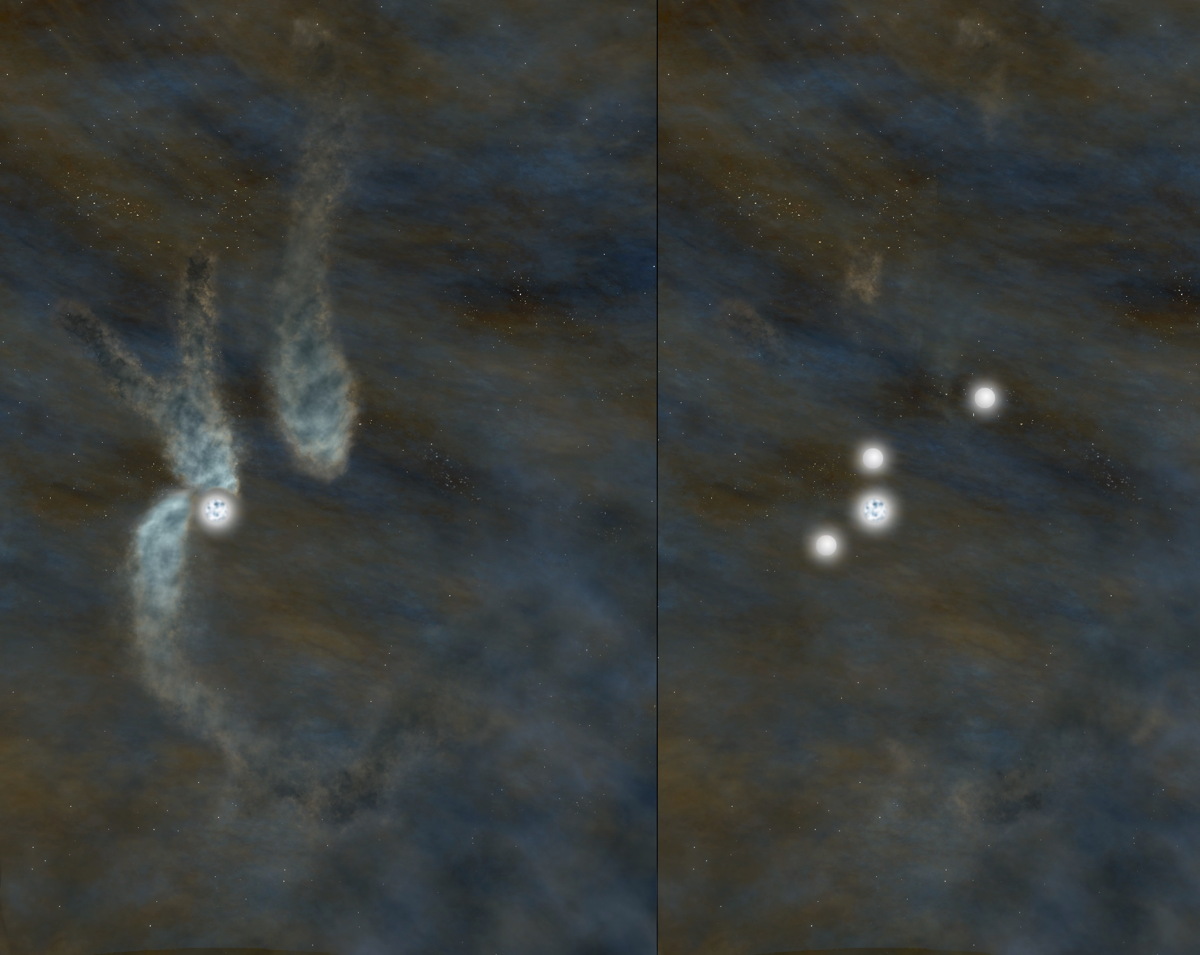

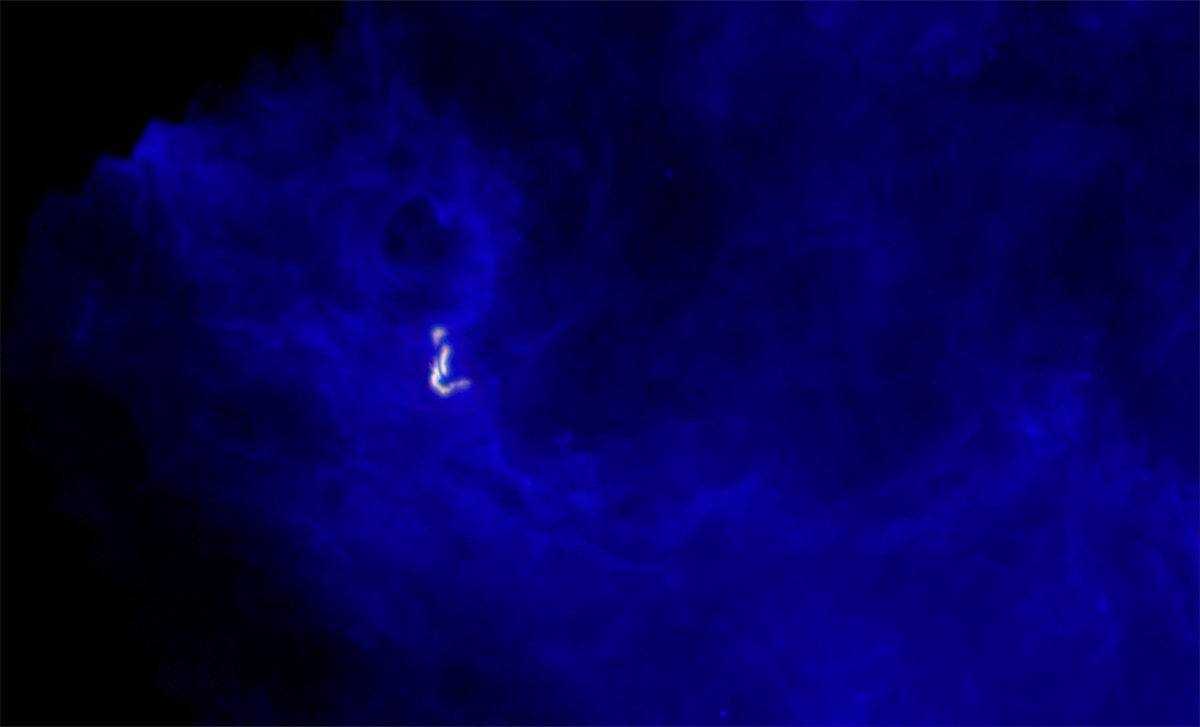

In the Perseus star-forming region, four stars are emerging from a single parent filament, and have been observed moving together as a family. Three of the siblings are balls of gas (within the larger gas filament) that researchers say are on the cusp of collapsing into stars, while the fourth sibling has already become a star.

Scientists estimate that more than half of all stars like our sun live with a partner star, and yet scientists have little observational evidence to suggest whether these stars are born together, like twins, or come together later in life. Double-star systems impact many areas of astronomy, including the search for black holes and for habitable exoplanets. The new findings could give scientists a better idea of how multi-star systems emerge. [Stars: The Life and Death Of Stellar Fusion Engines | Video]

Star families move together

The newly discovered star babies appear to be less than 100,000 years old, and may be the "youngest multiple star system," ever observed, according to Kaitlin M. Kratter, an assistant professor astronomy at the University of Arizona, who was not affiliated with the new research.

The new research shows that these four stars are forming from the same gas filament, and are linked together in a single system. But the stars (or soon-to-be-stars) are separated by 3 to 4 thousand astronomical units or AU (the distance from the Earth to the sun), which the authors of the new work say is a very large distance for star binaries. Normally, star twins are separated by only 10 to 1 hundred AU.

"These objects are so far apart that previously we all thought they were unrelated," said Jaime Pineda, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Theoretical physics and lead author on the new research. "But with the new observations, we can measure that these systems are really part of a whole. In this case it's the first time we can say it's like a family."

The researchers used three different telescopes to study the stellar babes. To show that the stars are part of the same family, the researchers had to measure their velocity, and show that they were moving as a unit.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If you don't know at what velocity the gas is moving you can't make this kind of study about the level of bound-ness of the system," said Pineda, who completed the research at the University of Zurich.

Star sibling rivalry

More than half of the stars in the universe are thought to exist in multi-star systems. It is through observing the motion of binary stars that scientists have identified black holes that have masses close to that of our sun. Binary stars can create Type Ia supernova, which scientists use to measure distances in the universe. Binary star collisions may create gravitational waves, or ripples in the fabric of space-time. Scientists have found potentially habitable planets around binary star suns.

"And yet the origins of the all-too-normal population are mysterious," said Kratter, in an article in the journal Nature discussing the new research.

Binary systems are highly common, but full-grown quadruple star systems are much rarer.

"Given the relative rarity of quadruple star systems at older ages, one might think this discovery improbable, or lucky," Kratter said. "On the contrary, it supports predictions that most stars begin their lives in a litter."

It's likely that after multi-star systems form, a kind of sibling rivalry sets in: the gravitational pull of all the bodies creates a highly unstable environment. While the researchers cannot say for sure what will happen to the four star siblings, Pineda said it's likely at least one of them will be ejected later on.

Kratter also notes that young stars have more bound companions than older stars, indicating that while stars may be born in groups, they eventually move away from home, leaving behind a smaller pool of siblings. Some double-star systems may contain stars that were born together, while ejected stars may form binaries somewhere else.

The new result is a tantalizing piece of evidence that could help astronomers understand how star families form. Based on the new finding, Pineda said, researchers may want to re-examine other groups of stars that were previously assumed to be part of separate systems, to see if they are, in fact, part of the same family.

"I think it's very likely that […] there are regions where we can repeat this experiment and try to determine […] in a more general way if this is a common result," Pineda said, "Or if we're looking at an odd ball."

The research is detailed online in the Feb. 11 edition of the journal Nature.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter