Glaciers on Mars Likely Helped Carve Red Planet's 'Grand Canyon'

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Signs of acid-rock interactions in Valles Marineris, the Grand Canyon of Mars, suggest that glaciers in the planet's past may have been responsible for carving at least some of the extensive network when the planet was more severely tipped.

While other deposits of the mineral, known as jarosite, have been found on Mars, the new signature is the first to suggest formation by ice, rather than by ponds or puddles of water.

"Jarosite is usually considered an evaporative mineral: it forms from acidic water that is evaporating," lead author Selby Cull, of Bryn Mawr College in Pennsylvania, told Space.com by email. [The Search for Water on Mars (Photos)]

Article continues below"Getting an evaporating pool of water halfway up a 3-mile-high cliff is tricky, and the more we looked into the geologic context surrounding the deposit, the less likely a liquid water origin seemed."

When acid meets rock

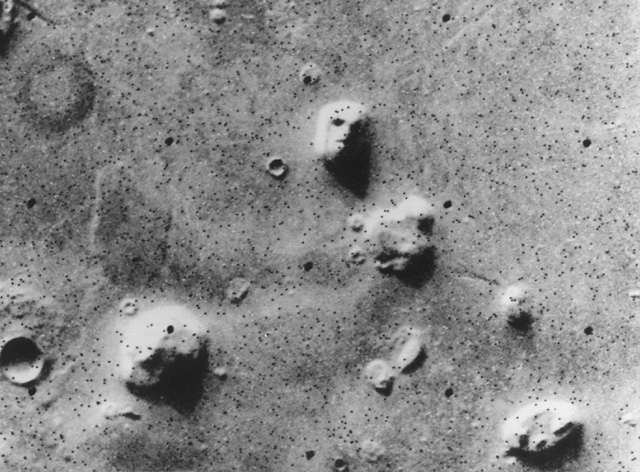

One of the largest canyon systems in the solar system, Valles Marineris is an extensive network running nearly 2,500 miles (4,000 kilometers) just beneath the Martian equator. The massive system is five times larger than Arizona's Grand Canyon— it stretches the length of the United States and encircles 20 percent of the Red Planet.

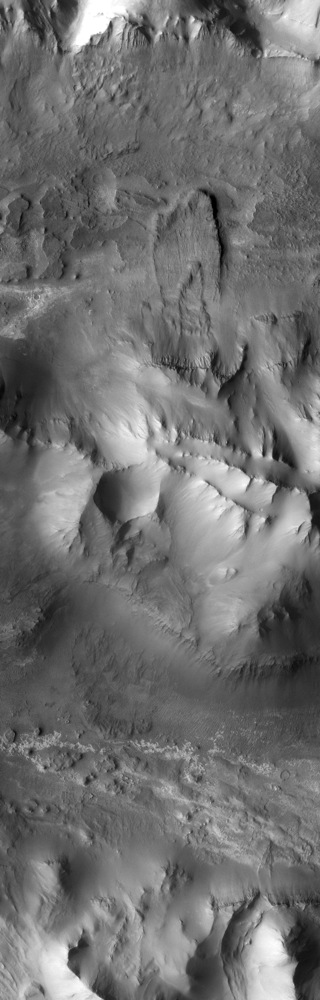

The Ius Chasma lies on the western side of the formation, and consists of two parallel troughs, each approximately 300 miles (500 km) long and up to 5 miles (8 km) deep, split by a ridge that runs between the two.

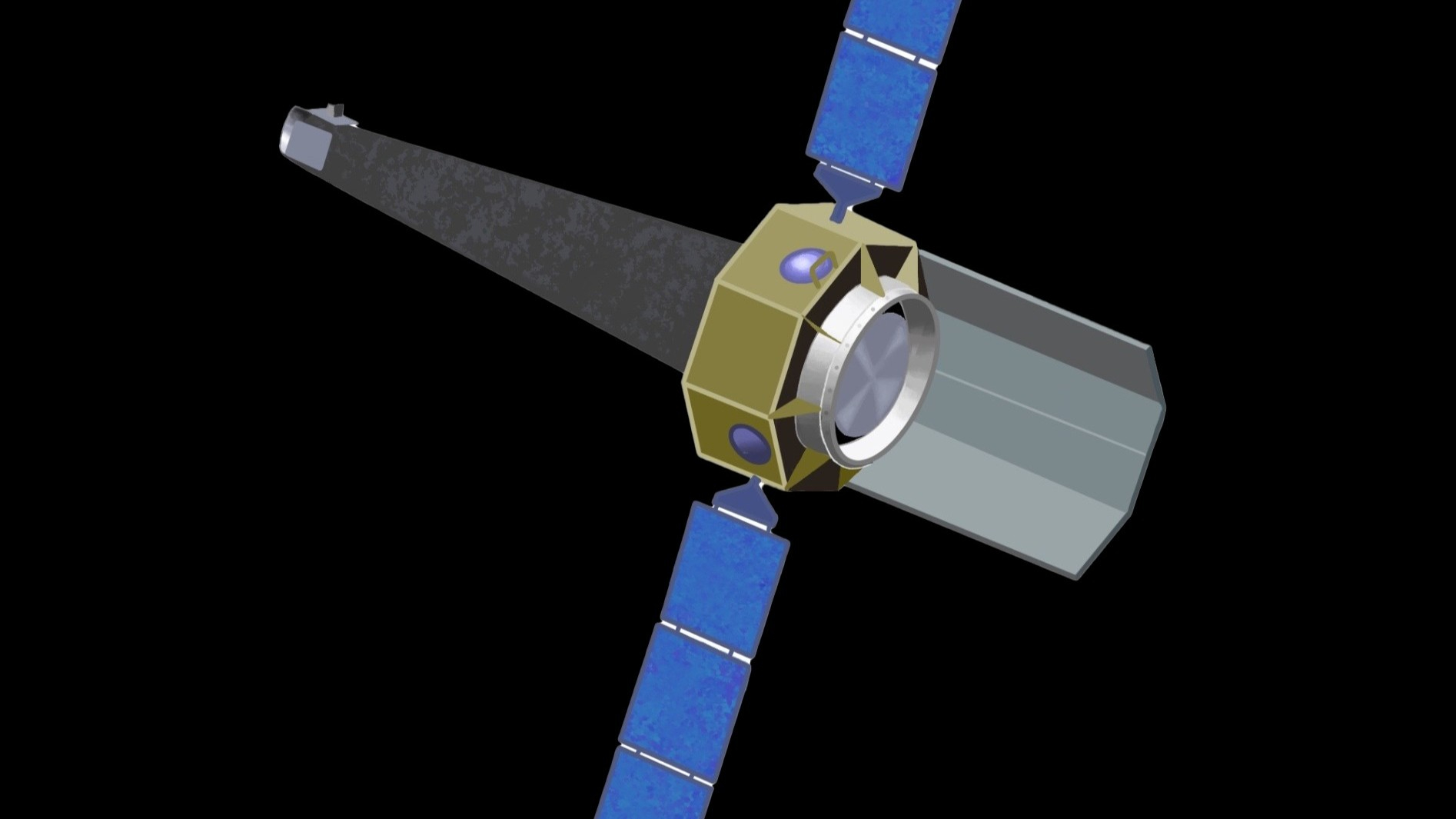

Using the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) onboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, Cull and her team found deposits of jarosite along Ius' southern wall, along with other sulfates and opal. A sulfate mineral, jarosite only forms in extremely acidic water on Earth, where it has been found in a wide range of environments.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"On Earth, jarosite has been found in acid-saline lakes in the hyperarid Australian deserts, in acid mine drainage systems like the Rio Tinto of Spain, as a result of 'acid fog' along the margins of volcanoes in Hawaii and Nicaragua, surrounding Arctic cold-water springs on Ellesmere Island [Canada], and along the margins of glaciers that interact with acid-producing minerals," Cull said.

"Of these, though, the only one that makes sense at Ius Chasma is the glacial origin."

Several other jarosite deposits have been have been found on Mars, but all of the previous regions appear to have formed by pooling or standing acidic groundwater that welled up from the surface and evaporated. The Ius deposits, however, lie well above the bottom of the canyon, leading the researchers to conclude they had identified a new style of acid-sulfate formation on Mars.

"If you were hiking through the Ius Chasma, and came upon these jarosite-bearing deposits, they would look like thick, bright layers in the canyon walls, poking out between reddish sand dunes," Cull said.

"There would also be giant boulders of bright white opal strewn about the cliffside."

The research was published in the journal Geology.

A once-icy equator

Various researchers have independently suggested that ice may have played a role in shaping Valles Marineris, though it is unknown how extensive such glaciation might be. The jarosite deposits in Ius Chasma follow a region that others have interpreted as a glacial trimline — the maximum height a glacier could reach in a valley. Furthermore, the layering of the deposits suggest that they lie only on the surface of the walls, rather than welling up from water behind the ground in back of them.

The combined evidence led Cull and her team to propose that the oddly placed formations could have been created by glaciers. The process would have had to occur when Mars had a stronger tilt to its axis, pushing today's equatorial region to higher latitudes.

"If glaciers formed on Mars during a time of high atmospheric sulfur — from, say, volcanic eruptions —then that sulfur would get trapped in the ice grains," Cull explained.

"Heating along the margins of the glaciers could cause tiny pockets of meltwater to form in the glaciers, reacting with the trapped sulfur to produce sulfate minerals."

If the small caches of meltwater had a high enough acidity, they could have created jarosite along the edges of the glacier, high above the canyon floor.

A similar formation process has been suggested along the margins of glaciers in Svalbard in Norway, where meltwater along the edges interact with nearby sulfide minerals to create deposits such as jarosite.

According to Cull, jarosite has a fairly clear signature, so as long as there is enough of it, it's fairly easy to spot with a satellite instrument such as CRISM. However, geologic processes such as erosion, alteration or burial by rockslides could have hidden other signatures in the chasm, which would explain why the team found jarosite in only one region of the basin.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky