Flexible 'Tentacle Robots' Could Aid Planetary Exploration

Space robots are about to get a whole lot sleeker and slinkier.

Researchers are developing new types of robotic systems inspired by elephant trunks, octopus arms and giraffe tongues. These flexible, maneuverable "tentacle robots" could have a variety of space applications, from inspecting hard-to-reach gear on the International Space Station to exploring crevices on Mars, scientists say.

"Those are all things that would be difficult for a conventional robot to do," roboticist Ian Walker of Clemson University said in April during a presentation with NASA's Future In-Space Operations working group. [The 6 Strangest Robots Ever Created]

A new kind of robot

The conventional robots to which Walker refers are mainstays of assembly lines around the world. They tend to be anthropomorphic, often modeled after the human arm, and are built to do one thing and do it well, over and over again.

These machines perform precision tasks in highly structured environments, with limited flexibility and adaptability, Walker said.

"What we want to do is something rather different than that," he said. The goal is to develop "something that can adapt its shape more completely down its structure, and to be able to adapt to environments you haven't seen before. So it's the non-factory scenario, in many ways."

Such snakelike robots could aid spaceflight and exploration, Walker said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

For example, astronauts could send them into rock cracks on the moon, Mars and other alien worlds, gathering data about intriguing environments that would otherwise be inaccessible or dangerous to explore. And relatively stout tentacle robots could help rovers anchor themselves when need be.

"You could reach it out into the environment and grab things, and basically use it as a tunable hook for stability," Walker said. "In some ways, this is inspired by various monkeys," which use their tails for the same purpose, he added.

Lithe, flexible robots could also check the outside of the International Space Station for damage caused by micrometeoroid strikes, Walker said. They could serve as useful general-purpose tools aboard the orbiting lab as well, wielded by astronauts or by NASA's humanoid robot Robonaut 2, which was designed to help human crewmembers perform menial tasks.

"They would basically have a robot lasso, or a robot rope, that would be part of their toolkit that they could deploy in situations that called for it," Walker said.

Making progress

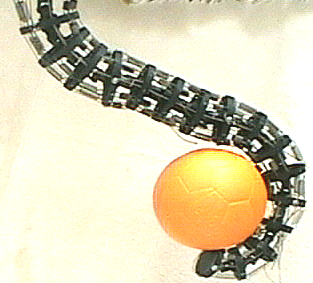

Walker and his team started working seriously on tentacle robots about 15 years ago. They've made a lot of progress since then, building machines inspired by elephant trunks, climbing vines and octopus arms, among other structures found in nature.

The octopus-arm project, which ran from 2003 to 2007, received funding from the United States' Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and involved researchers from six other institutions in addition to Clemson, Walker said.

The pneumatically actuated robot that came out of it, known as Octarm, could grab and stack cones of varying sizes, explore tunnel-like environments and manipulate objects it had never encountered before while submerged in water, Walker said.

Such machines are surprisingly inexpensive and easy to build, if the designers know what they're doing. Octarm, for example, cost just a few thousand dollars in total, Walker said.

"Mechanically, these things are cheap and very versatile in what they can do," he said. But the trick is "to extract that performance from it. So there are questions of, How much do you need to model it? How much does it need to know?"

While such challenges are keeping researchers like Walker busy, he thinks that tentacle robots have a bright future — and this future is likely not too far off.

"The learning curve has been significantly attacked, and I would say that we know an incredible amount more now than we did five years ago," Walker said, referring to the global community of tentacle robot researchers. "At the progress we're making right now, I would be surprised if there aren't things that look intelligent and [are] intelligent in, say, a decade."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.