Jupiter's Moon Europa May Have Plate Tectonics Just Like Earth

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

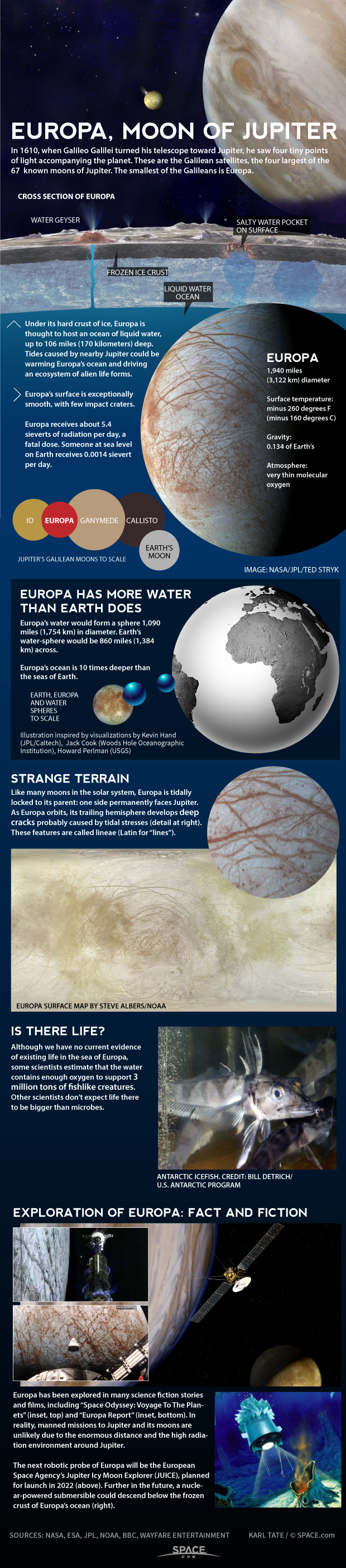

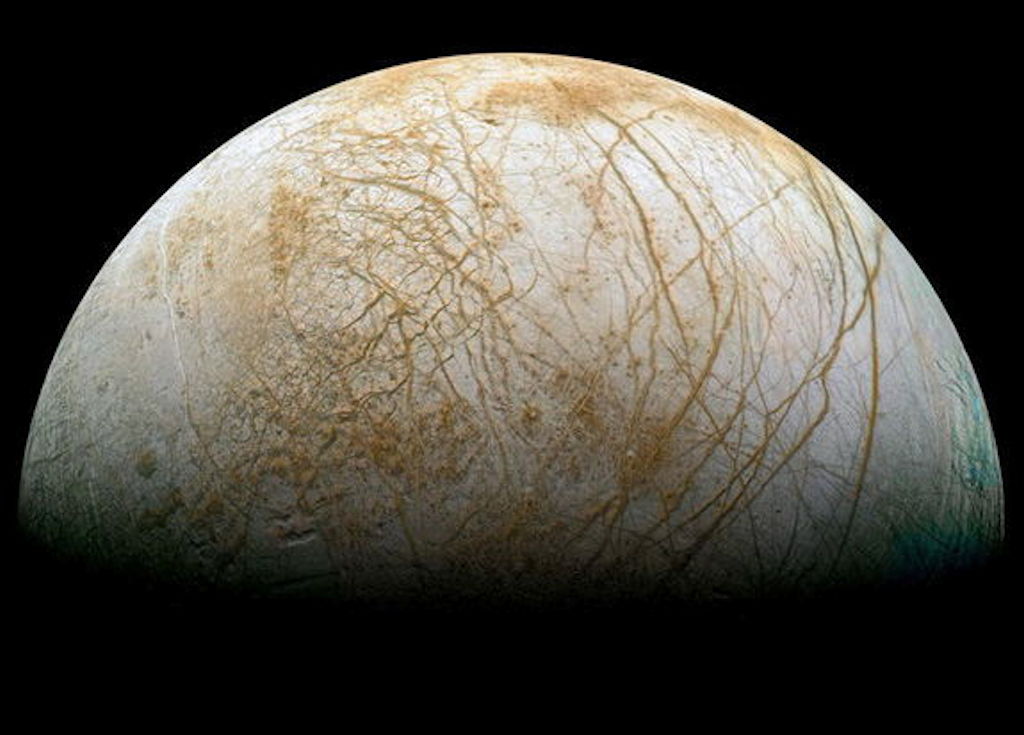

Jupiter's icy moon Europa, regarded as perhaps the solar system's best bet to host alien life, keeps getting more and more interesting.

Big slabs of ice are sliding over and under each other within Europa's ice shell, a new study suggests. The Jovian satellite may thus be the only solar system body besides Earth to possess a system of plate tectonics.

"From a purely science or geological perspective, this is incredible," study lead author Simon Kattenhorn of the University of Idaho told Space.com. "Earth may not be alone. There may be another body out there that has plate tectonics. And not only that, it's ice!" [Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter]

The new results come less than a year after plumes of water vapor were spotted erupting from Europa's south polar region. That find excited astrobiologists a great deal, because it suggested that a robotic probe may be able to sample the moon's subsurface ocean of liquid water at a distance, without even touching down.

"There have been a lot of recent exciting discoveries [about Europa]," Kattenhorn said. "All taken together, as NASA starts thinking about future missions, I'm hoping it will be pretty clear: This [Europa] is the obvious choice."

Missing puzzle pieces

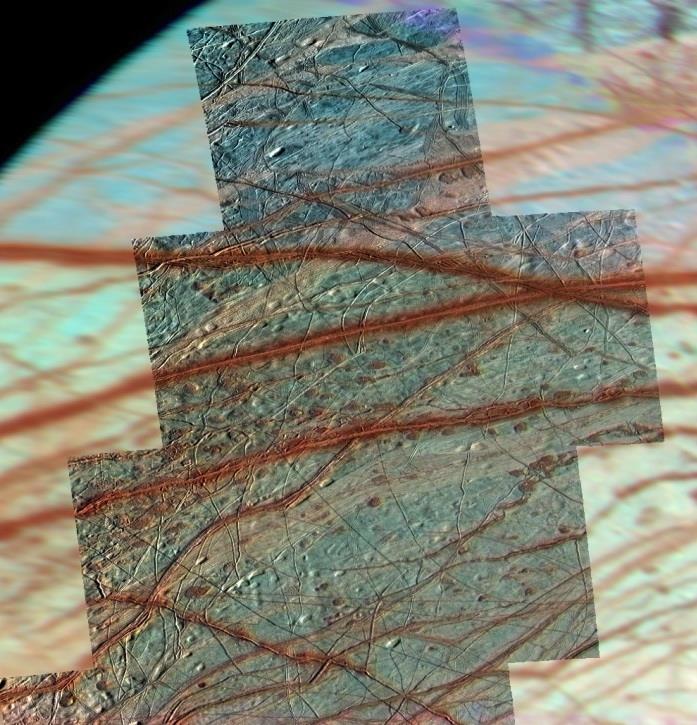

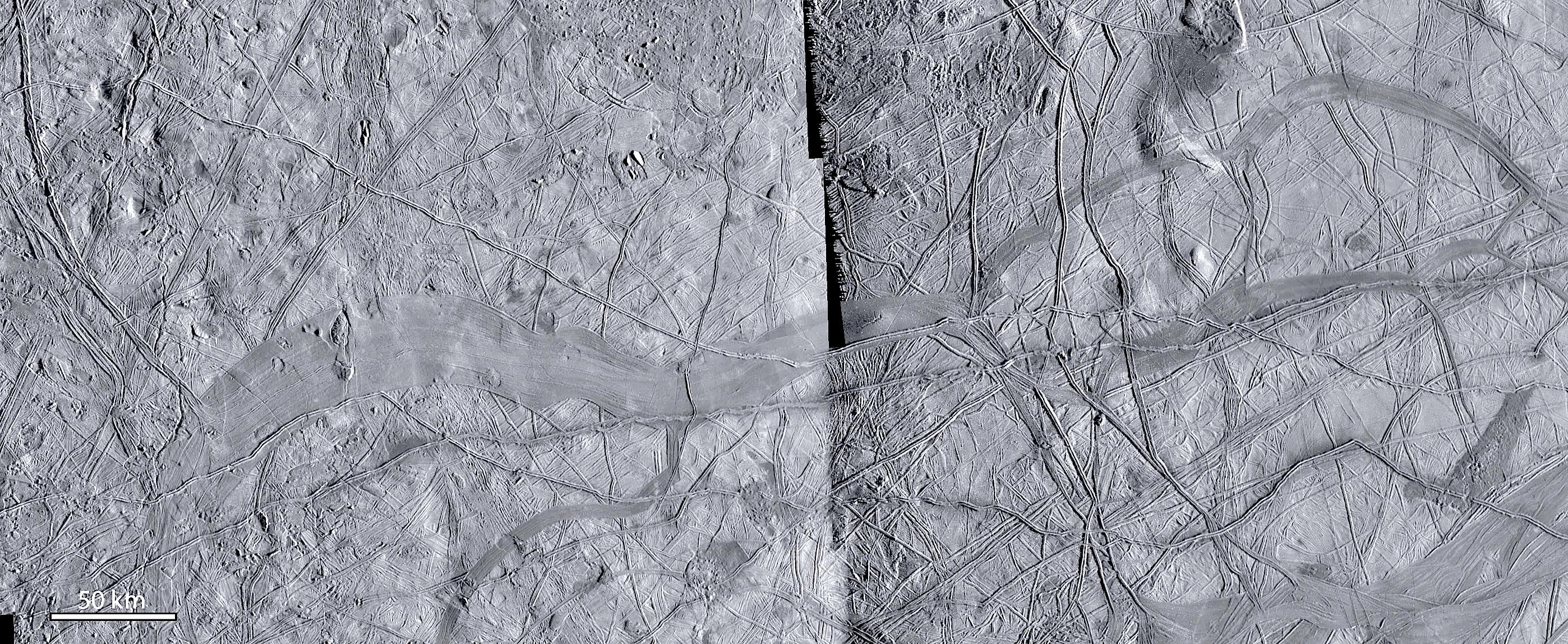

Kattenhorn and co-author Louise Prokter, of Johns Hopkins University's Applied Physics Laboratory, studied photos of Europa taken by NASA's Galileo spacecraft, which orbited Jupiter from 1995 until 2003.

The researchers used the images to reconstruct the recent geological history of a 52,000-square-mile (134,000 square kilometers) swath of Europa — an area about the size of the state of Alabama. They noticed that the region changed over time, with some surface features becoming mismatched relative to the architecture captured in earlier images.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It was very clear that you could reconstruct the original picture simply by moving plates around," Kattenhorn said, comparing the duo's approach to assembling a jigsaw puzzle.

Further, there was a gap in this reconstructed picture, as if a large puzzle piece had fallen off the table. In a sense, that's probably what did happen, Kattenhorn said.

"In this case, the big chunk had actually moved down underneath the adjacent plate and was forever lost, recycled into the interior" of Europa's ice shell, he said.

That chunk was indeed big, about the size of the state of Massachusetts, Kattenhorn added.

Plate tectonics

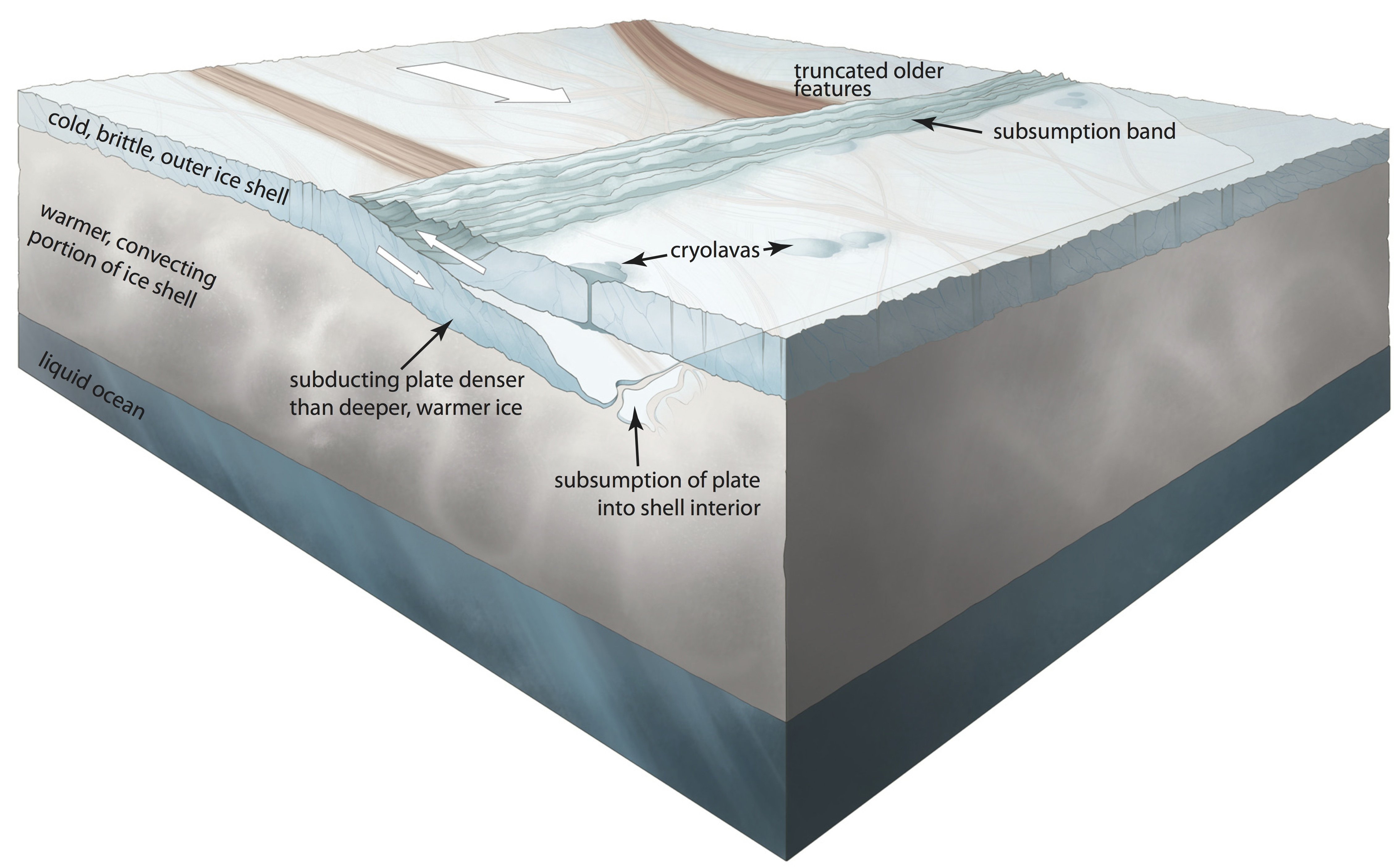

Kattenhorn and Prokter think this phenomenon of one plate sliding under another, which is known as subduction, is the most likely explanation for the disappearing puzzle piece. They cite several lines of supporting evidence, including potential "cryolavas" of water ice near the plate boundary. (On Earth, volcanism is common along subduction zones.)

If the scientists' interpretation — laid out in a study published online today (Sept. 7) in the journal Nature Geoscience— is correct, planetary science textbooks will have to be rewritten.

"Plate tectonics has been thought to be unique to our world," Michelle Selvans, of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, wrote in an accompanying "News and Views" piece in the same issue of Nature Geoscience.

"Subduction zones, convergent boundaries where one tectonic plate slides under another and is recycled into the Earth's mantle, are unique to plate tectonic systems," Selvans wrote. "Although Mercury, Venus and Marsshow clear signs of tectonic activity, such as systems of thrust faults and rift valleys, none of these rocky planets have been convincingly shown to have a system of moving tectonic plates, either today or in the past."

An active system of plate tectonics could also explain two puzzling facts about Europa, Kattenhorn said: 1) why its surface is so young (less than 90 million years, as estimated by meteorite-impact rates), and 2) how the moon accommodates the creation of new ice on its shell, which has been observed previously. (Europa isn't getting any bigger, so some process must be balancing out the production of new material.)

"From my perspective, that's pretty exciting, that we've addressed these two really important questions about Europa," Kattenhorn said.

He and Prokter said Europa likely has a system of cold, brittle plates moving around above convecting warmer ice. The mechanisms behind Europan plate tectonics are unclear at the moment, Kattenhorn said, stressing the need for modeling work. But tidal heating generated by the tug of Jupiter's immense gravity, the same phenomenon that keeps Europa's interior ocean from freezing up, may be one of the ultimate drivers, he added.

Implications for life?

Some scientists think plate tectonics were essential to the rise of life on Earth. For example, the idea goes, the movement of plates replenishes nutrients and helps stabilize the planet's climate by recycling carbon.

So it's natural to wonder if Europan plate tectonics may make the icy moon more habitable for simple lifeforms, Selvans wrote. [7 Theories on the Origin of Life]

"Perhaps Europa and Earth are even more uniquely similar: It is tempting to note the correlation between the existence of both life and plate tectonics on Earth and wonder if the latter might not be a requirement of the former," she wrote.

Europa's ice shell is thought to be 12 to 19 miles (20 to 30 kilometers) thick, and subducting plates likely dive down only a mile so, Kattenhorn said. Subduction, therefore, probably doesn't take any nutrients or other complex molecules from the surface down into the ocean immediately.

But this could happen indirectly and over longer periods of time via convection, he added.

"As with all convection, what goes up must go down as well," Kattenhorn said. "One can imagine that some of that material may ultimately, just by virtue of being in a convective system, work its way downward. Whether that ultimately comes into contact with the ocean is an important question."

And there may be pockets of liquid water within the ice shell relatively close to the surface, perhaps close enough to be reached by a subducting Europan plate, he added.

"People who are thinking about habitable environments — certainly not my field of expertise — that would probably be something very interesting for them to think about," Kattenhorn said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.