Saturn Season Shines in May Night Sky: Where to Look

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Saturn is now making its entrance onto the celestial stage, rising in the eastern sky soon after dark and shining brightly in the southern sky all night long.

To the naked eye, Saturn stands out in the May night sky as the only bright object in the constellation Libra. In fact it outshines the two brightest stars in this part of the sky, Spica to the planet's right and Antares to the left, and rivals Arcturus high above it.

New stargazers are often puzzled as to how to spot the planets among the stars. Most of the time, it's easy: The planets are almost always the brightest objects in the sky, largely because they are much closer to Earth than are the stars. [The Best Night Sky Events for May (Photos)]

Article continues belowIf you see what you think might be a planet, look closely at it. If it really is a planet, it will shine with a steady light, whereas a star will "twinkle." Turbulence in Earth's atmosphere easily deflects the light rays emitted by the distant stars, causing the apparent twinkling. Although planets look like points of light to the naked eye, they really are much larger in angular size, appearing as tiny disks in a telescope. This makes them less sensitive to the currents in Earth's atmosphere, and so they shine steadily.

Many new telescope owners are disappointed when they first look at a planet, because it appears so small in the instrument. Most telescopes allow stargazers to change eyepieces to observe with different magnifications. But don't be in a hurry to boost the magnification, which comes at a cost. The more you magnify a telescope's image, the blurrier it becomes, and the faster it moves from the field of view due to Earth's rotation.

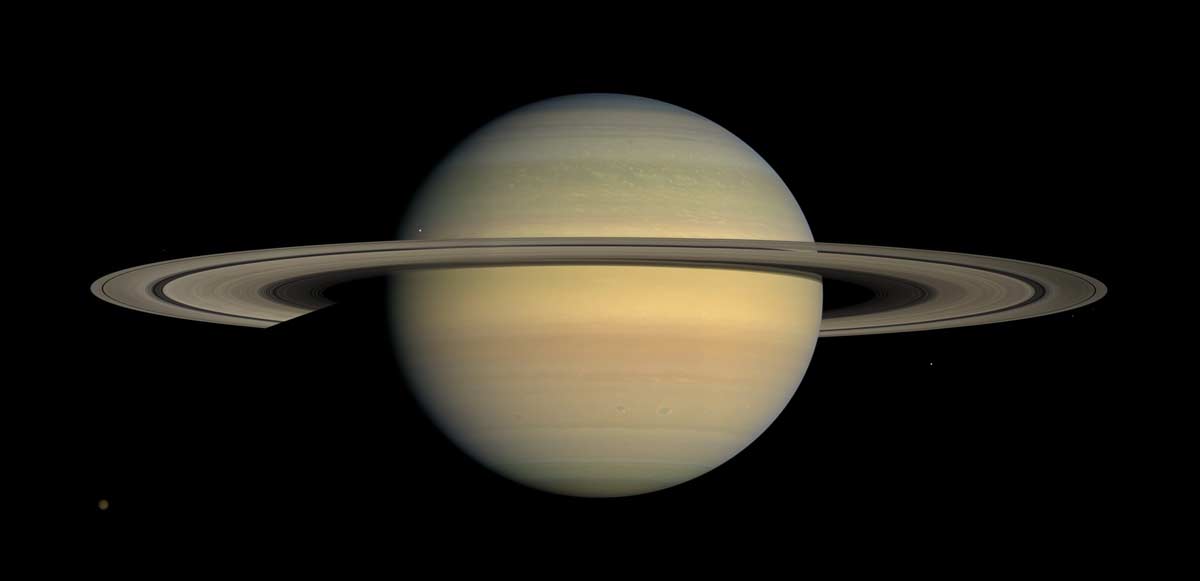

A magnification of about 25 times is adequate to see that Saturn is not a circular disk, but instead has an elliptical shape because of its rings. A magnification of 100 to 150 times is close to perfect for viewing Saturn. You can see the detail in the rings, the shadow of the planet on the rings, the shadow of the rings on the planet and the tiny specks of Saturn's moons. Any greater magnification will just intensify the blur of Earth's atmosphere without revealing any new detail.

Saturn's rings are actually in two parts: an inner, bright ring and a less-bright outer ring. You may be able to see a dark gap between the two rings, named the Cassini Division after Giovanni Domenico Cassini, who first spotted the gap in 1675. The rings are in an extremely thin plane directly above Saturn's equator. They consist of tiny particles, none larger than about 30 feet (10 meters) across.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So although the rings look solid from a distance, they actually are very thin and made up of individual particles with space in between them. As a result, Saturn's distinctive rings are actually transparent. Even when skywatchers have observed the planet's rings passing in front of a distant star, that object continued to shine brightly through the rings.

Saturn has a family of more than 60 moons, ranging in size from Titan, which is larger than the planet Mercury, all the way down to tiny moonlets less than a mile in diameter. Titan, with a diameter of 3,200 miles (5,150 kilometers), is large enough to be considered a world in itself, complete with a dense methane atmosphere, and a system of lakes and rivers containing liquid methane rather than water.

Iapetus sports another unusual feature: Its movement through the dust that surrounds Saturn has painted the moon's leading side black. When that side is angled towards Earth, Iapetus is fainter than when its bright, trailing side faces Earth.

Just looking at Saturn through a telescope, it's hard to identify the individual moons, but a program like Starry Night makes identification easy. In a 90mm telescope, skywatchers can see the six brightest moons: Titan, Rhea, Tethys, Dione, Iapetus and Enceladus. The positions of the moons change from night to night. Try making a sketch of their positions over several nights, and you will be able to trace their orbits around the planet.

Editor's Note: If you take an amazing skywatching photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

This article was provided to Space.com by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.