NASA Tests Orion Spaceship's Parachutes with Mock Glitch

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

NASA conducted a successful test of its next-generation spaceship last week, in an exercise designed to simulate two different types of parachute failures during landing.

A prototype of the Orion spacecraft landed safely in the Arizona desert May 1 after it was dropped 25,000 feet (7,620 m) from a C-17 airplane as it flew over Yuma, Ariz. During the test, the mock capsule was traveling about 250 miles per hour (402 km/h) when its parachutes were deployed — the highest speed the Orion spacecraft has experienced so far in its testing phase, NASA officials said in a statement.

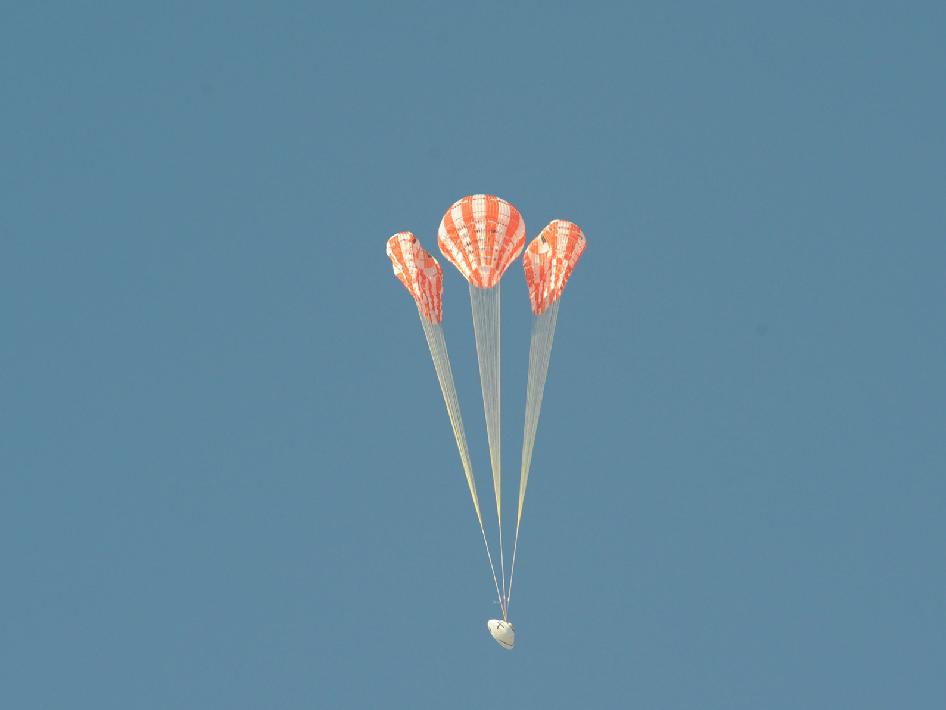

To simulate a failure, engineers rigged one of Orion's three main parachutes so that it did not inflate after the spacecraft was dropped from the plane. In addition, one of the two drogue chutes, which are used to reorient and slow the capsule as the main parachutes inflate, was not deployed. [Orion Capsule Survives Failed Parachute Test | Video]

Simulating a parachute failure enables NASA to demonstrate that the system is reliable even when something goes wrong. Data collected from the tests also help engineers refine their models and designs.

"Parachute deployment is inherently chaotic and not easily predictable," Stu McClung, Orion's landing and recovery system manager, said in a statement. "Gravity never takes any time off — there's no timeout. The end result can be very unforgiving. That's why we test. If we have problems with the system, we want to know about them now."

This type of parachute failure was one of the most challenging to simulate so far, but is a crucial step toward demonstrating that the spacecraft is safe enough to carry humans, said Chris Johnson, NASA's project manager for the Orion parachute assembly system.

"The tests continue to become more challenging, and the parachute system is proving the design's redundancy and reliability," Johnson said in a statement. "Testing helps us gain confidence and balance risk to ensure the safety of our crew."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Orion spaceship is being designed to carry astronauts on exploration missions to the moon, asteroids or Mars. The gumdrop-shaped capsule measures 16.5 feet (5 m) wide at its base, and weighs approximately 23 tons.

Orion's parachute system is the largest ever built for a manned spacecraft, NASA officials said. Fully inflated, the three main parachutes can almost cover an entire football field. During landing, the parachutes are designed to slow the capsule before it splashes down in the Pacific Ocean.

NASA will test Orion's parachute system again in July. For that test, the mock capsule will be released from a higher altitude: 35,000 feet (over 10,600 m). In September 2014, NASA plans to conduct the Orion spacecraft's first unmanned launch test.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Denise Chow is a former Space.com staff writer who then worked as assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. She spent two years with Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions, before joining the Live Science team in 2013. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University. At NBC News, Denise covers general science and climate change.