Look Up! Spot a 'Celestial Zoo' in the Night Sky

In the midst of the frantic "doomsday" buzz that swept the United States right before the Mayan calendar reached the end of its 5,000-year cycle in December 2012, I was approached by a person after I had given a presentation at New York’s Hayden Planetarium. They asked:

"If there is no basis to the Mayan prophecy, then how do you explain the sun’s alignment with the center of our galaxy that is predicted to occur on Dec. 21?"

Putting as earnest a look on my face as possible, I replied, "You’re absolutely correct … the sun will indeed be aligned with the center of our galaxy on Dec. 21." I then quickly added, "But of course that happens every year on Dec. 21." [End of the World? Top Doomsday Fears]

The look on my inquisitor’s face was priceless. "Really? But how can that be?"

The sun's annual path

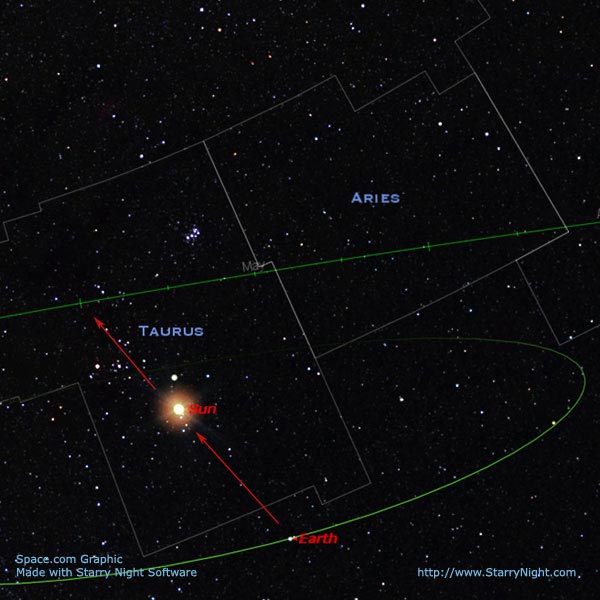

As the Earth moves around the sun, we see the sun change its position against the background stars — a full 360-degree circle around the sky during the course of a year. That apparent path is known to astronomers as the ecliptic, the extension of the plane of Earth’s orbit out toward the sky.

As it turns out, the moon and the seven other planets that comprise the solar system also move in orbits whose planes don’t vary too greatly from that of Earth’s orbit. As a result, the moon and the other planets also appear to stay relatively close to the ecliptic.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The sun never deviates from the ecliptic and so as Earth travels around it, from our perspective, it will always take the exact same path against the same background stars every year.

Since when we’re looking toward Sagittarius we’re also looking toward the center of the Milky Way, when the sun reaches that same point on the ecliptic in Sagittarius on Dec. 21 every year, the sun and the galaxy’s center are indeed aligned.

The ecliptic is a very important feature because it marks "the pathway," so to speak, for the sun, moon and planets as they move across the sky. Most sky charts plot the position of the ecliptic for this reason, for it provides sky watchers with a clue as to where one or more of these objects will appear.

Because they’re not located exactly in the same orbital plane as Earth, the moon and planets usually are not found exactly on the ecliptic line, but rather within several degrees of it. Thus, instead of a line, we find the moon and planets wandering along the sky within a band that encompasses the entire sky, which we call the zodiac.

The ecliptic runs exactly along the middle of that zodiacal band.

The 'classic 12'

The word "zodiac" is derived from the Greek, meaning "animal circle." A sort of "celestial zoo."

And with the sole exception of one of the "classic 12" constellations that belong to the zodiac, all of the zodiac members refer to living things. Many of these constellations are named for animals, such as Leo, the Lion, Taurus, the Bull and Cancer, the Crab, just to name a few.

The sole inanimate member is Libra, the Scales.

All of these names can be readily identified on sky charts and are familiar to millions of horoscope users (who — ironically — would be hard pressed to find them in the actual sky.) [Best Beginner Astrophotography Telescopes]

If we could see the stars in the daytime, we would see the sun slowly wander from one constellation of the zodiac to the next, making one complete circle around the sky in one year.

Ancient astrologers were able to figure out where the sun was on the zodiac by noting the last zodiacal constellation to rise ahead of the sun, or the first to set after it. Obviously, the sun had to be somewhere in between.

Each month a specific constellation was conferred the title, "house of the sun," and in this manner each month-long period of the year was given its "sign of the zodiac."

Some discrepancies

A couple of years ago, a board member of the Minnesota Planetarium Society caused quite a stir when he pointed out that the zodiacal sign that had been assigned for a given month in the newspaper horoscope is not where the sun actually is for that month.

He pointed out that, in reality, today’s astrologers continue to adhere to star positions that are out of date by at least a millennium. For instance, according to astrology, you’re a Leo if you were born between July 23 and Aug. 22 because that’s the time of year where the sun supposedly is in the zodiac.

That might have been true 1,000 years ago, but no longer. In fact, on July 23, the sun is not in Leo, but in Cancer. This discrepancy is due to the "wobble" of the Earth’s axis (known as precession).

As a consequence, there then came the revelation (even though it has been known by astronomers for a long time) that astrologers continue to adhere to star positions that for all intents and purposes are out of date by 10 centuries or more.

Outcasts of the zodiac

One thing that I have never been able to understand is why astrologers fail to recognize Ophiuchus, the serpent holder. He certainly should be considered as a card-carrying member of the zodiacal fraternity since the sun spends more time traversing through Ophiuchus than Scorpius.

It officially resides in Scorpius for less than a week: from Nov. 23 to 29. It then moves into Ophiuchus on Nov. 30 and remains within its boundaries for more than two weeks — until Dec. 17. And yet, the serpent holder is not considered a member of the Zodiac.

In addition, because the moon and planets are often positioned either just to the north or south of the ecliptic, they sometimes appear within the boundaries of several other non-zodiacal star patterns.

The revered Belgian astronomical calculator Jean Meeus has pointed out that there are actually 22 zodiacal constellations in which the moon and some of the planets from Mercury to Neptune can occasionally enter.

In addition to the 12 classical zodiacal signs and Ophiuchus, we can also add: Auriga, the charioteer; Cetus, the whale; Corvus, the crow; Crater, the cup; Hydra, the water snake; Orion, the hunter; Pegasus, the flying horse; Scutum, the shield; and Sextans, the sextant.

And in case you’re interested, in the upcoming month, the moon will be in Orion on May 13, Sextans on May 19 and Ophiuchus on May 26.

I guess you can say that so far as the celestial zoo is concerned, these three constellations are on the outside of the cage looking in.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for the New York Times and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, New York. Follow us on Twitter, Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.