Jupiter's Atmosphere Has Weird Hot Flashes

Though Jupiter is shrouded in swirling clouds, its atmosphere has some mysterious clear patches that scientists call "hot spots."

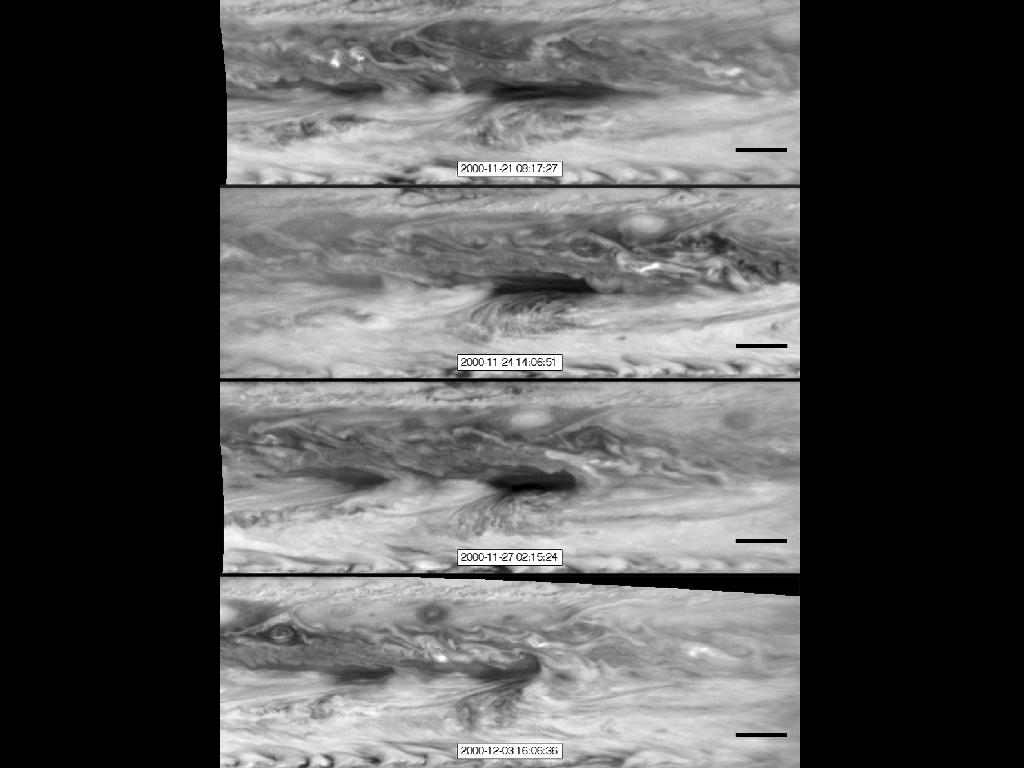

Now researchers say they have found more evidence about where these hot flashes come from by stitching together images taken by NASA's Cassini spacecraft nearly 13 years ago.

"This is the first time anybody has closely tracked the shape of multiple hot spots over a period of time, which is the best way to appreciate the dynamic nature of these features," David Choi, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., said in a statement.

Hot spots get their name because they appear bright in infrared images of Jupiter, which detect heat. In the visible spectrum, these patches appear shadowy. Scientists think that the clearings could represent windows into Jupiter's atmosphere all the way down to the level where water clouds can form, researchers said. A NASA video about Jupiter's hot spots explains how the odd phenomenon works.

Choi and his colleagues put together images from two months (in Earth time) of Cassini's flyby of Jupiter in late 2000. Their time-lapse movies focus on a line of hot spots about 7 degrees north of the equator that are each about the size of North America and almost evenly spaced apart.

The researchers teased out the individual movements of the winds around each hot spot and Jupiter's jet stream, which actually allowed them to measure the true wind speed of planet's jet stream: an impressive 300 to 450 mph (500 to 720 km/h). The hot spots, meanwhile, move along at 225 mph (362 km/h), the researchers found.

The motions of the hot spots fit the pattern of a Rossby wave in the atmosphere, the team reports. Rossby waves are also found on Earth and are sometimes blamed for extreme changes in weather. For example, a Rossby wave can interact with the polar jet stream and sent a blast of Arctic air to chill Florida.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers believe a Rossby wave circles Jupiter moving west to east, rising and falling possibly 15 to 30 miles (24 to 50 kilometers) in altitude instead of moving north and south over the planet.

Their findings are detailed online in the April issue of the journal Icarus.

NASA's Cassini spacecraft launched in 1997 and flew by Venus, Earth and Jupiter on its way to Saturn. The orbiter arrived at Saturn in 2004 and dropped the European Huygens probe onto the planet's largest moon Titan.

Cassini's primary mission ended in 2010, with NASA extending the spacecraft's voyage twice. The latest mission extension will allow Cassini to study Saturn and its moons through 2017.

Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Megan has been writing for Live Science and Space.com since 2012. Her interests range from archaeology to space exploration, and she has a bachelor's degree in English and art history from New York University. Megan spent two years as a reporter on the national desk at NewsCore. She has watched dinosaur auctions, witnessed rocket launches, licked ancient pottery sherds in Cyprus and flown in zero gravity on a Zero Gravity Corp. to follow students sparking weightless fires for science. Follow her on Twitter for her latest project.